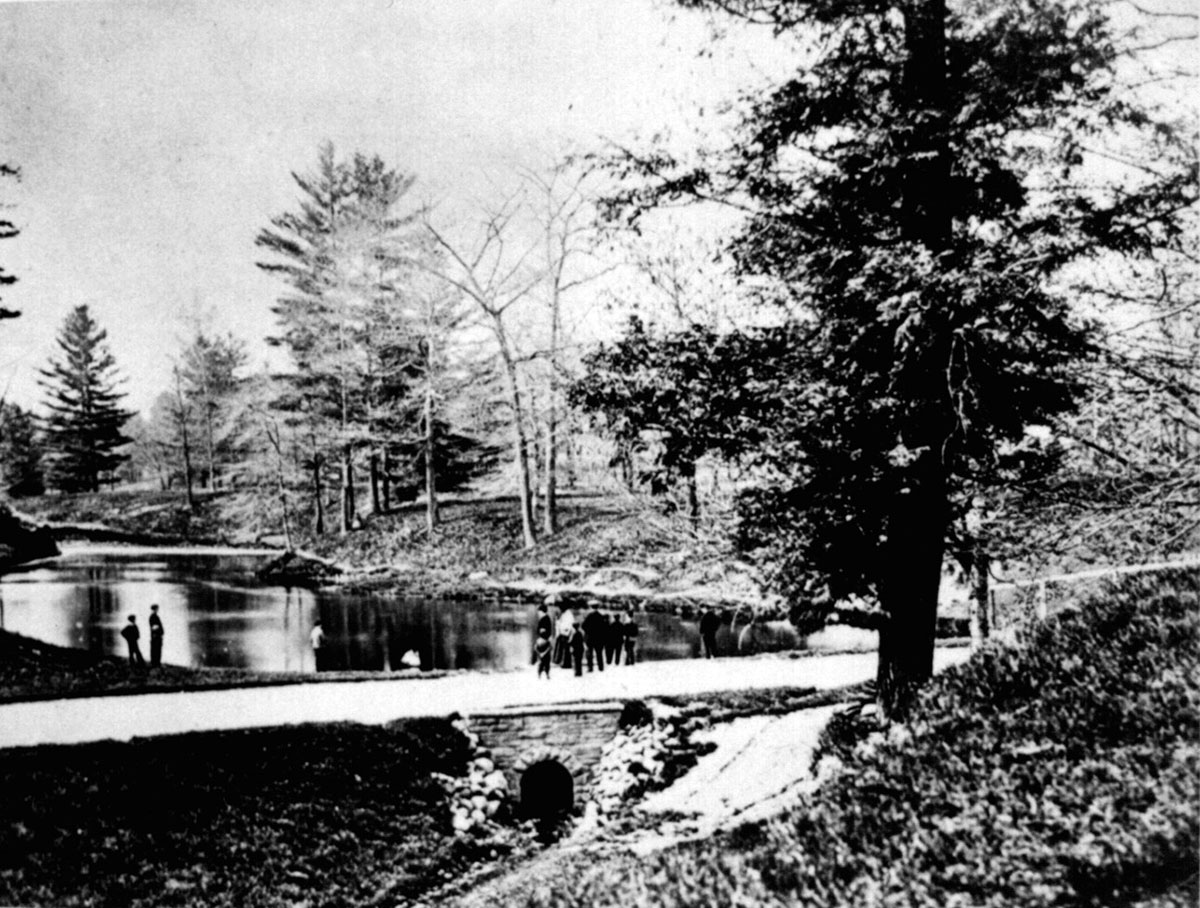

Taddle Creek at the University of Toronto, circa 1876.

It’s such a Toronto thing to do. You take something beautiful, make it wretched, and bury it. Then, a hundred years later, recognizing both error and opportunity, you dig it up and make it bloom. Such is the history—some of it yet to unfold—of Taddle Creek, the vanished but fabled stream that once ran through midtown and downtown Toronto.

No cynicism is implied here, nor any rural, pastoral yearnings or laments. Toronto has gotten along quite well without Taddle Creek, a resource that was discovered, appreciated, and carefully used by native peoples, but closer to our times ran against the flow of progress.

Indeed, while the Victorians praised Taddle’s primordial beauty—University College at the University of Toronto was deliberately sited with good views of the brook, which was dammed here into a picturesque pond—they promptly polluted it. Architect-designed brick and stone mansions with parquet floors, shingled turrets, and water closets in the Annex north of Bloor Street, generated a less elegant antithesis at the less elegant end of the pipe.

In The City in History, Lewis Mumford laments the ease of flushing and the waste it represents. Many cultures learned agriculture, he found, but those that eventually thrived were the ones that learned to make farming self-sustaining by fertilizing the land. “[W]here human as well as animal dung was fully used, as in China, even the growing city offset its own blotting out of valuable agricultural land by enriching the surrounding fields,” Mumford mused. “If we knew where and when this practice began we would have a deeper insight into the natural history of early cities. Water closets, sewer mains, and river pollution give a closing date to the process: a backward step ecologically, and so far a somewhat superficial technical advance.”1

Taddle Creek had its parallels, among them Garrison Creek in the far west end, and lesser-known Russell Hill Creek nearer in. All were inspired by gravity, the source of which was the Iroquois shoreline,2 the ancient bluff of Lake Ontario that rises just north of the Canadian Pacific railroad tracks that cross central Toronto. It is a significant slope, a moraine that meanders east until it is interrupted by the Don Valley and eventually becomes the Scarborough Bluffs. “Sparkling with hope and promise, they spring from the hills of Davenport, only to be captured and forced into the dark netherworld of Toronto’s underground,” memory columnist George Gamester wrote in the Toronto Star a few years ago, commenting on the three creeks’ common fate.3 Taddle’s source, then and now, is said to be the pond in Wychwood Park, partway up the incline, but it is known to have had many tributaries. These include the now-absent stream in the Albany Avenue area that gained national attention a few years ago when David Suzuki told how the citizens’ group Grassroots Albany, long familiar in these parts, wanted to uncover it and make it part of the landscape again.4

That these waterways continue so strongly in a big city’s stream of consciousness, long vanished but somehow known by citizenry who cannot have known them, demonstrates the power of collective memory and moisture’s tendency to persist. As recently as 1985, when Metro Police were erecting their new Gucci headquarters at College and Bay streets, Taddle Creek sprang forth in protest, from seventy feet below, demanding a change of plans.5 After crossing Bloor Street and meandering south to College Street, Taddle would have had to make a pretty abrupt easterly turn at the university to get to the site where police headquarters now stands, so it’s very likely we’re talking here about another tributary. In any case, the result had to be a shallower basement and reinforced walls, and perhaps in the future police may also be blessed with that bugaboo some Toronto homeowners must deal with due to Taddle—rising damp in the basement.

The gurgling at police headquarters gave rise to other Taddle memories, as Gamester later recalled: “The Park Plaza Hotel was another Taddle victim in the 1930s. Before engineers corrected the problem, uneven settling of the hotel’s foundations caused it to lean about 15 centimetres out over Bloor St. For a while, the hotel was known as “The Leaning Tower of Park Plaza.”6

Taddle Creek is perhaps most identified with, and lives on in memory most fondly, at the University of Toronto, whose campus the stream bisected between Bloor and College streets. Extant photographs justify the praise, showing the stone spires of University College reflected idyllically in the waters of the little lake created when a dam was built near where Hart House now stands. So perfect does it seem that one wonders to what extent these photographs, and perhaps even the landscape itself, constitute a sophisticated public relations effort, designed to evoke just the right associations needed to sell the facility to faculty, students, and their upstanding middle- and upper-class families.

As a matter of fact, such planning was not at all foreign to the Victorian sensibility. “To an age with an appetite for ‘picturesque’ effects, no landscape was complete without its decorative stretch of water, and Taddle Creek and the ravine in which it ran obviously lent itself to sympathetic imaginings,” U. of T. art historian Douglas Richardson wrote in his chronicle of University College, A Not Unsightly Building. “‘By the planting of its banks, and the heading of the running water,’ Henry Rowsell thought it [Taddle Creek] ‘capable of being formed into a object of great ornament to the domain.’”7

There were even plans to install a botanical garden just east of the lake, about where Queen’s Park Crescent now carries traffic.8 It was never built, but the University College grounds indeed became, Richardson writes, “a semi-rural retreat with living space of its own, set apart from the city. It had its own garden which grew food for the College kitchen, while the wide fields behind provided pasture for the cows which supplied it with milk. A quiet lake, McCaul’s Pond, named for John McCaul who was U. of T.’s first president,9 fed Taddle Creek in its valley of willows, rushes, and thick stands of trees.”10

What a contrast it must have presented in the muddy, grotesque, nineteenth-century city. An account recorded by a freshman on arriving at U. of T. around 1860 describes “a beautiful pond, closed in with forest trees, the eastern edge blue with some curious water flowers, and at the upper end of the still blue surface a number of ducks were swimming about.”11 Spring and summer found students lolling about, “picking wildflowers and chasing butterflies” and even fishing for trout, meanwhile in wintertime skating on McCaul’s Pond and tobogganing on Taddle’s banks. Seniors dunked first-year students in hazing rituals each September—bully for them—and youngsters sailed toy boats.12

U. of T. students gave Taddle Creek life. It was also U. of T. students who sealed its fate. Abraham Lincoln once said that “public sentiment is everything…he who moulds a public sentiment goes deeper than he who enacts statues or pronounces decisions.”13 A scary thought, since media then as now were not exactly owned democratically. The student-run Varsity may not have been a Hearst rag or Colonel McCormick’s Chicago Tribune, but it knew a safe cause to champion when it saw one. The newspaper took it upon itself to notice Taddle’s increasingly unappetizing waters, made so by the drains of the new McMaster Hall (now the Royal Conservatory of Music), which fed directly into Taddle, augmenting the existing polluting efforts of the Annex and Yorkville. Varsity editors set out to mould the public’s desire to get rid of it. “The stench arising from the Taddle is very pronounced,” the Varsity announced. “The prevalence of so much fever in the city is surely a good reason for the prompt abatement of this long-standing nuisance.”14

In city politics universities tend to get what they want, and the clout of U. of T. was deployed efficiently to the desired end. A contract to bury the creek in pipes and conduits was let in 1884. Wrote a Varsity poet, expressing no discernible regret, “The City Council would thy stream immure, and shut thee up with breaks and lime secure, and make thee—Ichabod—a common sewer, Taddle.”

McCaul’s Pond, looking toward the east wing of University College, circa 1876 . . . and today.

It must have seemed the right thing to do, much as building highways to meet the demand of traffic seemed to be the right thing to do in the nineteen-sixties. But there are often evil undercurrents in good intentions, and the catch in the case of Taddle Creek was simple. Burying it merely transferred the pollution problem to a bigger arena, Lake Ontario, and with a thousand other similar creeks buried or finally just ignored, the big lake didn’t stand a chance. Moreover, the principle “out of sight, out of mind” exacerbated the problem, for while the smell and squalor of sewage had prompted other civilizations to develop means of final disposal—or at least made them reckon more directly with the consequences of their own existence—Lake Ontario was big enough and far enough away from where most people lived that discharge there seemed like the final solution. When finally it wasn’t, sophisticated sewage treatment then seemed like the answer, but it has its limitations, especially in Toronto. Here sanitary sewers serving homes were never fully separated from storm sewers taking runoff from streets and rooftops. After major storms, the volume of water overwhelms the city’s sewage pipes and treatment facilities, and the overflow, a brew of household and toilet waste mixed with less offensive storm water, pours untreated into the lake and becomes a major source of contamination.15

The nature and scale of planned solutions, not unlike the existing problem, boggle the mind. One of the last gestures of Toronto council before the city was folded into the new megacity of Toronto was the approval of a seventy-million-dollar, four-kilometre holding tunnel, five metres in diameter, that will be bored through bedrock between Parkside Drive and the Canadian National Exhibition grounds.16 The purpose of the tunnel is to receive and store the overflow after each storm, until treatment plants catch up with the volume. It will probably work, as so much does in Toronto, but seems both grandiose and uningenious.

McCaul’s Pond.

Philosopher’s Walk is a path that starts at Bloor Street at a handsome gate marked by a pair of historic electric lamps. But the promise of the name, and the grand gateway, is not fulfilled. The Chinese would say the walkway, which follows the former watercourse of Taddle Creek, has bad feng shui—it is not a comfortable, welcoming place to be. The reasons are partly physical, partly spiritual. When you walk down the ramp from Bloor Street to the bottom of the creek’s ravine, you feel vulnerable and alone; indeed fear of crime has led the university to install an emergency call box along the walkway near the Edward Johnson music building. An Ojibway lawyer, John Borrows, who studied at the U. of T. law school bordering the walk, has commented on the uneasy meeting between the surviving, indigenous landforms left by the creek—its empty ravine and its high banks and the “western systems of planning and architecture” superimposed on them. They “have joined the law in privileging Western preferences,” he writes. “These streams were the springtime gathering places for the Ojibway.” But now “the spirits of land and water are buried and submerged. The stream is concealed, the fish are gone: people no longer gather to this site to witness the spectacular reproduction of life once present.17

Can this loss be repaired? Much has changed in the hundred years since Taddle Creek was buried, including thinking about sewers and pollution, cities and city life. Some time ago a study for Toronto’s Waterfront Regeneration Trust, which has been grappling with the Lake Ontario discharge problem, suggested that one answer may lie in the city’s covered creeks. Ecologists have found that natural plant and water systems, though susceptible to concentrated pollutants, also possess an amazing ability to purify water and break down chemicals and contaminants typically found in storm water with natural enzymes. One proposal for Garrison Creek in the west end would restore the waterway to its ravine with ponds designed to catch sediment, waterfalls that add oxygen, and wetlands to catch and consume nutrients considered undesirable in Lake Ontario.18 Downstream, the result would be much clearer water, and less need and pressure for more complex treatment facilities or big, costly buried pipes. Meanwhile, the by-product for the city would be, in these places, a reconciliation between the built and natural environments, which late-twentieth-century thinking has realized can not only coexist, but also support each other. Indeed, quite aside from their function, the filtering devices the uncovered streams would become would provide significantly upgraded urban parkland. The late city of Toronto left the door open, if only a crack, to such alternatives, not only by funding feasibility studies for Garrison Creek but also Taddle Creek. Partly under pressure from community groups in midtown, the city and the University of Toronto are being forced to consider the same possibility for Taddle Creek. Caught by surprise, the new megacity might find such a project politically useful, given the need to appease Toronto’s still suspicious burghers, and, compared to big pipes, more economically attractive. U. of T., something of a bully in city affairs, except when pushed and cajoled and embarrassed or bribed to be otherwise, can be expected to resist until it is time to revel in the congratulation and good public relations the achievement would bring.

The tale of Taddle Creek is a story still interactive, whose ending will be shaped by the sensibilities of a new millennium. It could go either way, as Toronto is swallowed up in a much larger political landscape. The rope in the tug of war will be lengthened, extending from the Pickering border to Mississauga, and it will be interesting to see whether praise for diversity extends beyond race to intellect and aspiration. The scale of thinking may change; it will be harder to make the details matter. Suburban voters are more penny-pinching, more republican, and to them what was Toronto may seem all too foreign and threatening. Compared to the suburbs, the old city is enormously complicated and full of apparent contradictions: a city of street cleaners and street people, fancy public gardens and grubby back alleys, Bay Street suits and shirtless squeegee teens, rumbling, clanging streetcars beneath glittering skyscrapers. Digging up an old sewer would be a Toronto thing to do. But does Toronto still exist? That is the question of the hour, in this bizarre time of transition. I will be waiting, with apprehension, for proof one way or the other. I expect to find it in the waters of Taddle Creek.

Notes

- Lewis Mumford, The City in History (New York: Harcourt, Brace & World, 1961), 14.

- Jacob Spelt, Toronto (Toronto: Collier—Macmillan Canada, 1973), 6.

- George Gamester, “Three Forgotten Streams Run Through City’s Heart,” Toronto Star, April 17, 1995, sec. A, p. 4.

- David Suzuki, “How Annex’s Grassroots Seed Grew Into A Movement,” Toronto Star, Sept. 12, 1992, sec. D, p. 6.

- Darcy Henton, “One Less Floor For Police Station After Underground Creek Found,” Toronto Star, Nov. 7, 1985, sec. A, p. 1.

- Gamester, “Forgotten Streams,” sec. A, p. 4.

- Douglas Richardson, A Not Unsightly Building (Toronto: Mosaic Press, 1990), 76.

- Richardson, A Not Unsightly Building, 54.

- Ian Montagnes, “Taddle Tale,” Graduate, (September/October, 1979): 15.

- Richardson, A Not Unsightly Building, 14.

- W. J. Loudon, The Golden Age: Studies of Student Life, as cited by Montagnes.

- Montagnes, “Taddle Tales,” 15.

- Richard N. Smith, The Colonel: The Life and Legend of Robert R. McCormick (New York: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1997), xi.

- Montagnes, “Taddle Tales,” 15.

- Brian McAndrew, “Sewer Tunnel Plan $11 Million Over Budget,” Toronto Star, Oct. 4, 1997, sec. A, p. 4.

- McAndrew, “Sewer Tunnel,” sec. A, p. 4.

- John Borrows, “Buried Spirits,” University of Toronto Bulletin, March 3, 1997, p. 16.

- Alfred Holden, “Taddle Creek, Lost To View But Found In Memory,” University of Toronto Magazine, (Winter, 1995): 43.