Frederick Banting built his house at 46 Bedford Road after winning the Nobel Prize. Today, it is the site of Taddle Creek Park.

Taddle Creek Park, on this cold, March morning, is a frozen, dug-up pit. Tree roots stick out from the sides of berms, where retaining walls once held back dirt. At the rear of the small midtown Toronto park, two pieces of heavy equipment sit abandoned beside a locked-up portable site office. In the park’s centre are piles of gravel and other rubble, covered in a thin layer of fresh snow. A beat-up bench, the last remnant of infrastructure from the park’s original 1978 incarnation, can be seen in the debris, and the once-popular (if modest) fountain that was the park’s centrepiece has been bulldozed. Wire fencing surrounds individual trees and the site’s perimeter. Fastened to the fencing are various metal signs warning, “DANGER DUE TO CONSTRUCTION,” “DANGER DUE TO MOVING EQUIPMENT,” and, oddly, “TRAIL CLOSED.” Trail? Well, there was a diagonal walk, heavily used, crossing through the half-acre green space here at Bedford Road and Lowther Avenue, just steps north of Bloor Street West in the Annex. The path took you past a large, old beech, a small playground, the fountain, and a mulberry tree that, in season, dropped messy, staining fruit on a seat beneath it.

In recent years, Taddle Creek Park had become especially threadbare from decades of hard use, and its current reconstruction, which began in November, 2010, was the fruition of years of community lobbying for improvement. Toronto is home to older parks, bigger parks, and better parks. Taddle Creek Park’s role is best described as a working park—busy doing its job, something not all the more well-known parks can claim.

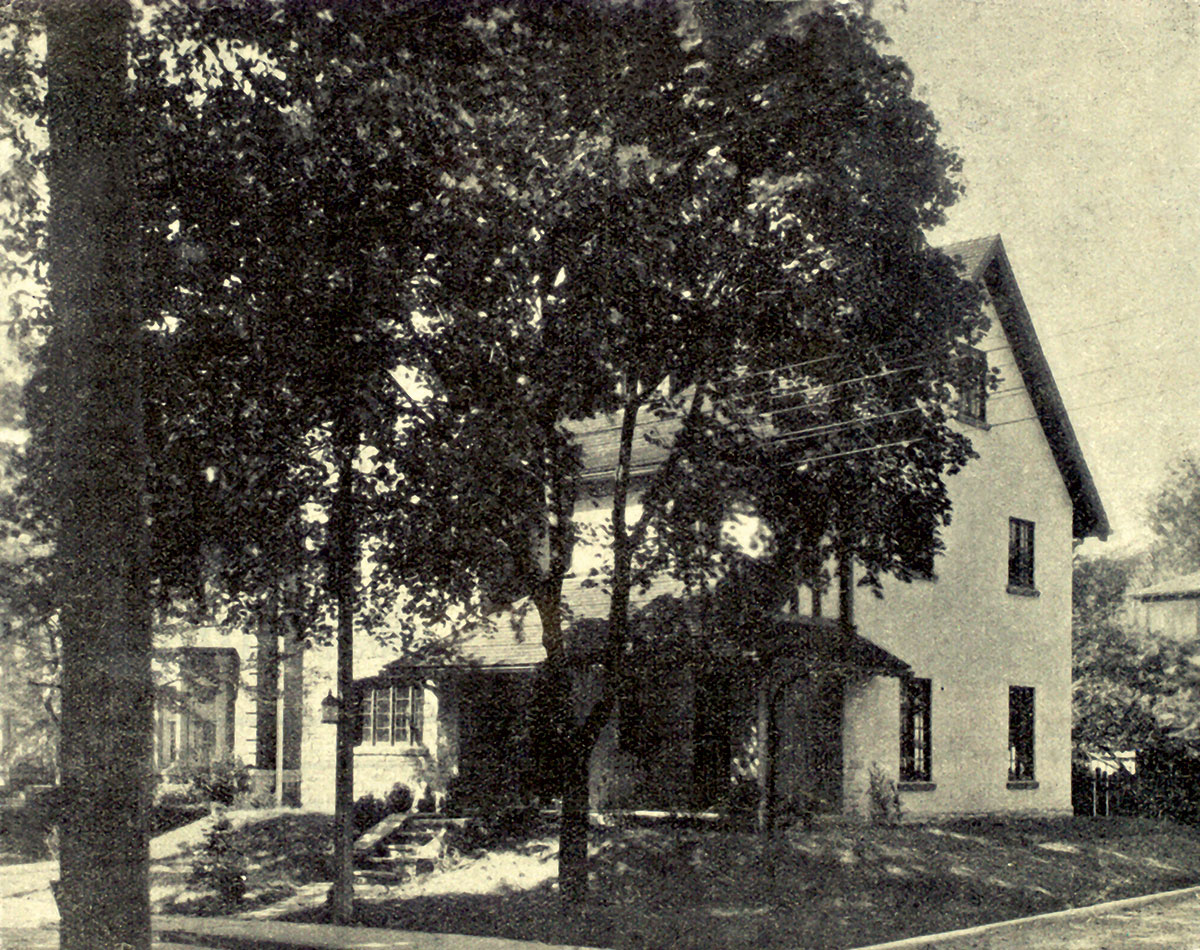

That March morning I met at the park with Josh Fullan, an Annex resident and a teacher at the nearby University of Toronto Schools. Fullan worked the park’s renewal process into a civics lesson for his high-school students, who, in May, 2010, used Taddle Creek and two other nearby parks to conduct a Jane’s Walk—one of a series of tours aimed at connecting people to their neighbourhoods, named after the author and urban thinker Jane Jacobs. Fullan and I surveyed the debris. At one point he pulled out a picture of a commodious-looking home, once located at 46 Bedford Road.

“Professor Frederick Grant Banting, 38, of the University of Toronto, proceeded from his home in Bedford Road, Toronto, a warmish morning last week,” Time reported in its September 29, 1930, issue. “His University this morning…was going to dedicate his splendidly-equipped Banting Medical Institute.” Banting’s institute still stands on College Street, east of University Avenue, part of that area’s great medical complex. His home, the same 46 Bedford Road, is gone. Banting had built the house after winning the Nobel Prize in medicine, in 1923, for co-developing insulin. Today, its former location is part of the site of Taddle Creek Park.

Rich McAvan, the landscape architect in charge of the park’s redesign, told me engineers working late in 2010 were surprised to discover house foundations as they dug. “You’re doing directional boring to put your electrical cable in,” he said, “and boom—you hit a wall.” A closer look at the piles of muck and debris reveals an assortment of yellow and red bricks, of the type once used to build our houses in Toronto. Viewed on a bright March day, it was close-at-hand evidence of now-remote times and lives.

The original Taddle Creek Park and its fountain, circa 1979.

It’s unusual for houses to become parks. Fullan alluded to “tensions” being a vital current in Taddle Creek Park, “tensions between what it was, what it almost was, and what it’s going to be.” In 1962, Tadeusz (Ted) Lempicki, a former officer in the Polish army who’d come to Canada in 1948 and eventually founded a construction company, began buying up homes along Prince Arthur Avenue, Bedford, and Lowther, with a plan to build apartment houses. With surprise and some regret, he discovered while going over old mortgage documents that he’d probably set up his office in Frederick Banting’s own study. He mentioned it to university and medical friends, but, he said later, “Nobody seemed too excited.”

Old houses weren’t Lempicki’s thing. The land acquisition for his project had been complicated, and he didn’t feel like starting over. The loss of Banting’s house may have been inauspicious, but it was a watershed moment for Taddle Creek Park—physically because the land it now occupies would be cleared, and figuratively in that the idea of a park on this site would now take hold.

By 1964, at a time when it was hard to get approval for dense high-rise development in the Annex, Lempicki sought out the progressive architect Irving Grossman to design his apartment block. “When I saw the drawings I said: ‘Irving, you are crazy,’” Lempicki told Frank Jones, of the Toronto Telegram, the following year. Grossman’s plan, according to Jones, included “the carrot to encourage ratepayer support. A half-acre park, complete with playground equipment would be provided for the public in an area notably starved of parkland.”

Lempicki proposed a deal in which he’d donate the land for the park in exchange for the city’s blessing to build two twenty-three-storey apartment houses—a somewhat bigger complex than zoning then permitted—to be known as Prince Arthur Square. One alderman called the idea “a little bit of candy” (i.e., a bribe), telling the Globe and Mail, “If he wants to throw in the park after the development committee [has approved rezoning] then we can accept it.” The deal didn’t go through. In the end, a single nineteen-storey building was constructed at 50 Prince Arthur, with lots of room around it.

Jim Lemon, a longtime Annex resident who lives on Walmer Road, remembers seeing hoarding around the would-be parkland for years. “Our youngest daughter went to the daycare at the Quaker meeting house [at the corner of Lowther and Bedford],” he said, “and I remember going over there, facing that fence every day.” Lempicki went on to build a handsome high-rise, 190 St. George Street, one of Toronto’s earliest condominiums, a block west of the park, in 1971. But then he disappeared from the scene, with the site at Bedford and Lowther still empty.

Paradoxically, the developer’s idea of having a park on the lot stuck, and in 1973 Annex residents began urging the city to buy the land. The Bedford-Lowther Park Committee, made up of interested members of the community, was formed in 1976 and soon the site of Frederick Banting’s mansion, that hadn’t been turned into a high-rise after all, was city property. Paul Martel, an architect who lives on Admiral Road and sat on the park committee, supplied a design to meet the group’s criteria: “The park should have 12 month use….Trees should be used on the perimeter….There should be water to look at, for noise and to walk through.” With its diagonal pathway that served as a shortcut to the subway from Admiral Road and the densely populated St. George Street apartment houses, and its small playground, Taddle Creek Park worked hard, shaping the neighbourhood. At a bench in its west corner, teenagers met in privacy. Annex parents, or their nannies, made use of the playground. I met my spouse at the fountain, both of us having come to soak our feet in the pool during the hot summer of 1988.

As Fullan and I walked from Taddle Creek Park past 1 Bedford Road, the tall new condominium at the corner of Bedford and Bloor, he mentioned the irony that a deal with that building’s developer, made under Section 37 of Ontario’s Planning Act, is now paying the cost of fixing up Taddle Creek Park in 2011. Such arrangements, known as “let’s-make-a-deal planning,” may have rattled aldermen in 1965, but today they are commonplace, and the best way to get a shot of infrastructure when the city is short on tax dollars.

Ilan Sandler’s Vessel, the park’s new jury-chosen centrepiece, days after its May installation.

Renewing a park is a convoluted process, involving committees, citizen input, and general bureaucracy. Mayor Rob Ford’s gravy train is a partisan fabrication. In reality, the workings of municipal government are plodding, penny-pinching, a tad paranoid. Toronto “really struggles to maintain and look after its parks,” says Fullan. He adds that his students “couldn’t believe the glacial progress of these things. They could have come to high school and left and never seen anything done to the park.”

Prior to receiving the Section 37 money, an ad-hoc committee of local residents had worked up a no-frills plan for the park—a freshening of what was already there, including new playground equipment, fresh landscaping, and something to replace the rotting railroad-tie retaining walls along the outer edges. “We were pretty sure we could raise that money,” says Frank Cunningham, of Admiral Road, a University of Toronto philosophy and political science professor and co-chair of the Annex Residents’ Association’s planning and zoning committee. But suddenly, with money from 1 Bedford, a diversion in the plans for Taddle Creek Park began. A noted landscape architect was hired by the city to come up with a new design. Cunningham recalls plans for “trees surrounded by cement doughnuts where people would sit, a terrific park for people on a lunch break.” Some liked its echoes of the nearby Yorkville’s acclaimed, self-consciously artsy park, much used by office workers at lunch that also, as a matter of fact, boasted pine trees in the middle of cement doughnuts. “The overwhelming majority of people didn’t like it,” says Cunningham. “I thought it was horrendous. [So the city] dusted off the old neighbourhood plan. And they liked that plan.”

Over coffee, Rich McAvan walked me through the drawings for the new Taddle Creek Park, the paper already dog-eared and mud-stained. A cheerful man in his thirties, with salt-and-pepper hair, McAvan calls himself “a meat-and-potatoes” kind of landscape architect, which makes him a fitting choice to design such a hard-working space. The familiar park—the cracking fountain, the worn-out benches, the interlocking pavement—is there, on paper. We turn a page, and it’s gone. Peeling down the layers, staggering amounts of technical data appear covering everything from grading to water management. When the park re-emerges, many sheets down, it is the familiar one in new clothes—the same layout, now with square and rectangle block paving, plantings of dark red and yellow spireas, an army of evergreens, and no annual flowers.

The only thing to survive from the rejected avant-garde scheme is the park’s new centrepiece, The Vessel, a sculpture by Ilan Sandler, a Nova Scotia–based artist whose design won a city-run juried competition. “Here I think [opinion] was more evenly divided” than on the park design as a whole, Cunningham says. The sculpture took a large part of the park’s budget, he complains, but won advocates on Admiral Road and around the park. The work consists of stainless-steel rods that have been welded into the shape of a 5.7-metre-high jug. Water will be pumped to the rim, where it will be released to splash down the rods. One imagines it all translucent-seeming and sparkling in the sun, with wet children cavorting around the semi-circular benches at its base. According to the artist, the four kilometres of tubing used reflects approximately the distance Taddle Creek once flowed from this spot in the Annex to Lake Ontario. Cunningham mocks the subtle reference as “ludicrous,” though I remind him allusion is the artist’s stock-in-trade.

McAvan thinks the public’s first impression of The Vessel will be, “That doesn’t belong here.” But he predicts people will get used to it. One planned feature is to collect the water in an underground tank, and use it to irrigate the park’s grass, flowers, and trees, another allusion to the real Taddle Creek, whose meandering waters nourished the primeval forest that once stood here.

By mid-April, during a wintry spring, work began again in Taddle Creek Park, with construction progressing at a breakneck speed. Soil was backfilled into the new retaining walls, baby evergreens went in on the slopes of the berms, and wooden forms appeared for the base of the new playground, which had already arrived and sat partly assembled inside the fence.

In the mind’s eye, parks are idyllic places, an absence of city, or relief from it. Cunningham foresees “a better park from this,” but muses about a “tragedy of the commons” circumstance, whereby those whose money restored it, the residents of 1 Bedford, by their sheer numbers put the little park in peril. Fullan, who walks by the park every day going to and from work, spun it the other way. “It’s not a bad place for a high-rise,” he said to me, about 1 Bedford, showing an increasingly sophisticated acceptance of dense urbanity in neighbourhood-centric Toronto. The park will be used as before—heavily. Taddle Creek Park, finally, is not a dreamy Frederick Law Olmsted, or a Warhol-era Michael Hough, who landscaped such brutalist landmarks as the University of Toronto’s Scarborough campus, or a Yorkville-esque boutique park. It is a hard-working, inhabited pad of grass, cement, and trees. “There’s tension,” Fullan says again. “Between our desire to build the city vertically and yet protect things like green space, heritage properties, and streetscape integrity. But it’s a very interesting tension.”