Jane Jacobs had a few weaknesses. One, we learned, was sweets.

In September, 2004, I was asked to act as the interviewer and moderator of a Q. & A. session with Jacobs, at Harbourfront, in conjunction with the launch of her book Dark Age Ahead. Hosting isn’t my specialty, but I know enough to start with small talk—something to put both the interviewee and the audience at ease. Someone had recently told me butter tarts were a distinctly Canadian sweet, and I was sure that Jacobs, a former American, with special takes on Canada, would know something about them. As it turned out, she did like butter tarts, knew of their Canadianness, and wondered aloud about their history, drawing gamely on her wisdom. People laughed, of course—just what was needed to leaven the more serious discussion to come.

Jacobs must have struggled with her celebrity, perhaps even resented it at times. Celebrity commands respect—it gives one access to people who have the power to implement ideas, and must be excellent for the ego. But the price is constant interruption, which is a curse and a temptation to all writers, and can stall both projects and accomplishment. So Jacobs wisely limited interviews, gracefully declining to talk about a book until it was ready, occasionally jumping in on behalf of her publishers or her ideas, but then retreating back into her work.

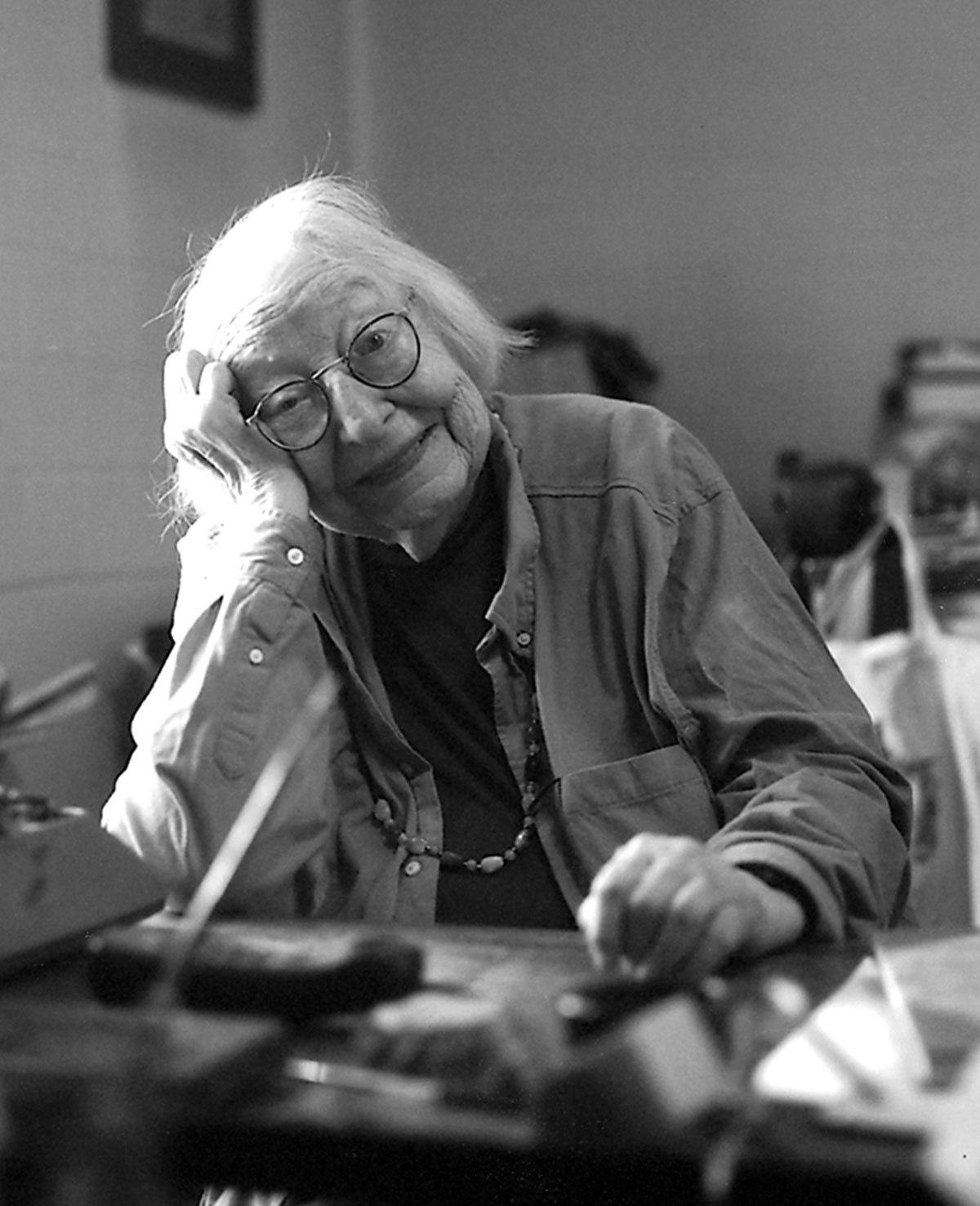

Several months before my Harbour-front debut, I interviewed Jacobs for this magazine, in her upstairs writing room, at the back of 69 Albany Avenue. It was cluttered and unpretentious, a former apartment kitchen. This time, she conducted the small talk, breaking the ice by asking me about my Annex Gleaner column, which she graciously said she read and liked. She also noticed the vintage four-by-five camera Taddle Creek’s photographer Phillip Smith, who had accompanied me, had brought along to snap her picture, and listened with great interest as Phillip told her the story of how he had found it in the trash on a New York sidewalk.

Her publishers may not have always let on, but Jacobs was in fact, as Phillip and I saw that day, very accessible, and certainly friendly. It was not uncommon to run into her around town, especially in the Annex. My first encounter with Jacobs was in 1984, at the corner of Bloor and Markham streets, on Ed Mirvish’s seventieth birthday, when he and Jacobs led a walking tour of the neighbourhood. (Last time I looked, my brief report on it, for the Toronto Star, was still hanging amid all the other posted clips on the west wall of Honest Ed’s.) We later met again, by chance, in a small office above a Bloor Street store, the office of Nadine Nowlan, like Jacobs, a veteran of the battle to stop the Spadina Expressway.

Jane Jacobs never claimed to be perfect, or clairvoyant, though you might be tempted to think she was after reading The Death and Life of Great American Cities, written well before much of the potential destruction described in its pages actually happened. One of the criticisms of Jacobs was that she was hard on planners, many of whom adopted her outlook and sought to implement her ideas. From this she never budged; she resisted being labelled a planner herself, though many a planner thought her the master.

What will we think of Jane in ten, twenty, fifty years? We may never know Jane Jacobs the person any better. But we will surely discover and rediscover her ideas, learning something fresh and valuable each time, something that, like the ideas in her books, might make life better, and just might help save us.