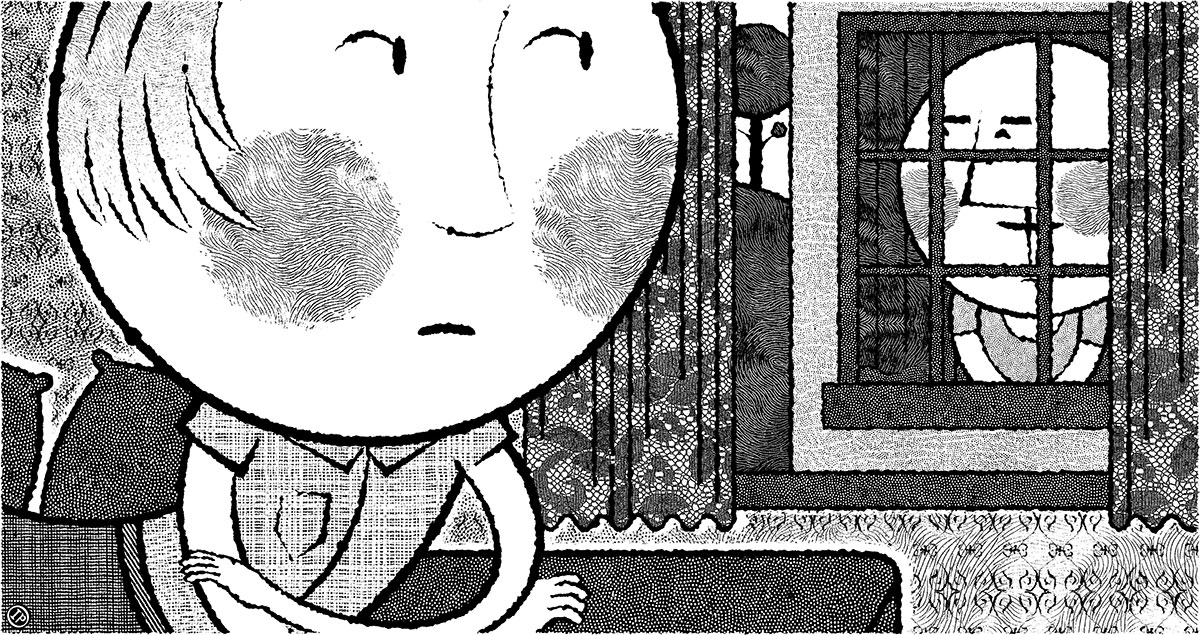

When I was thirteen, I lived in my room and I hated everything. I hated my room. I hated my suburb of Green Vista. I hated my mother. I hated my ugly white brick school. But, most of all, I hated my media studies teacher, stupid Mr. Carter, who lived behind us in an ugly bungalow. I could see his room through a crack in my curtains from where I’d lie on my bed. He never closed his curtains, so I always had to have mine closed. I wasn’t missing anything. My window looked out on a dumb view anyhow—nothing to see but other people’s swimming pools and petunia borders. “Marnie, don’t be so negative,” my mother always said. Mom would get mad at Anne Frank for being scared of the Nazis. She would think Anne Frank was being “negative.”

I was already disgusted with adults smiling their funny tight smiles whenever they got embarrassed. They hated it whenever anyone got mad. That embarrassed them too, and I embarrassed them all the time. When I embarrassed them they got this fake smile, but, underneath, I could tell they were freaking out. You could be dying in my house, but, if it would be embarrassing to save you, they wouldn’t save you. So, when they really should have listened to me, they just sent me to my room and smiled that little Catholic smile.

When adults looked at me their faces closed up and they’d smile a little and they’d think I couldn’t see them shake their heads. Except our neighbour, Mrs. Martini.

Mrs. Martini told Mom once that I was going to be a knockout when I grew up. My mom looked surprised and smiled that little smile. My mom doesn’t really like Mrs. Martini. My mom would think it was rude to be a knockout. There’s a rumour that Mrs. Martini was once a stripper. You could hear my mom thinking, “Marnie is not good looking. She is not petite.” I pictured myself as a knockout. I’d be on TV with shiny, bouncy hair. Would I ever be mean to the men. Only the most brilliant men could have me. It would be just like Gram’s romance novels, which I read when I went to her place. She died when I was twelve, but we both used to stay up late reading the gothic romances together, even though they are so stupid and the heroine always fights with the hero at first and she’s always, like, a total knockout with “eyes too wide for beauty” or a “reed-slim figure,” but they pretend she’s really plain. If I was a knockout, I would be so skinny that I would borrow little boys’ clothes when I fell into the river or something. All the men would fight over me and I would choose the one who impressed me most. Then that one would turn out to be mean and tie me up and hit me and then the real one I should have loved, the one I argued with at first, would save me, just like in the books. But I wasn’t a knockout. I was size fourteen with greasy, straight brown hair and brown eyes. Boring, boring, boring. I didn’t even have a waist, so maybe Mrs. Martini was just trying to be nice.

I liked Mrs. Martini; she made good maple fudge even though she wanted Freddy, the German shepherd across the street, put down because he jumped on her when she was holding the baby. I liked Freddy because he’d follow me to school and I’d have to take him home and miss class. Finally, he was sent away though. He killed the Boulders’ cat in the driveway.

When it was happening, all the adults stood around the cat, afraid of Freddy because he was big. He used to always only pay attention to me because I love animals and he could tell. I was maybe gonna be a vet or an album cover designer like Klaus Voorman who did the Revolver album for the Beatles. But Freddy didn’t even see me that day. He didn’t pay attention when I called him or anybody called him. He kept smiling and jumping onto the old cat. It was just a furry, bloody lump on the concrete, but somehow the cat would hiss and scratch in Freddy’s mouth when Freddy grabbed it again and again.

The trashy teenager from two doors down, big Linda, with her tight jeans and tank tops, started swearing. “Somebody get the dog the fuck away from it!” The adults looked more scared that Linda was swearing than that Freddy was killing the cat. Nobody ever swore on our street. Every time Freddy grabbed the cat, my stomach opened up in a huge hole that went right to my eyes. Mr. and Mrs. Boulder looked so upset, but nobody could get near Freddy. I hated the adults for just standing there. The next time he let go of the cat, I ran to him and grabbed his collar and dragged him away. “Here Freddy, here Freddy,” I said. I was scared. He looked like he was going to bite me. There was blood on his grin. They scooped up the cat and took him away to be put down.

I let go of Freddy when the cat was safe and stood around for a few minutes watching the adults shake their heads and talk to each other. Nobody thanked me. I went to my room even though I wanted to scream and run around. I didn’t even really like my room, but it was the only place I could go.

After I tried to kill Mr. Carter, I was lying on my bed in my room looking at the John Lennon collage I was pasting on the wall and the adults were downstairs in the living room “discussing” me. This time the adults were Mr. Carter, my mom, and my dad. Dad, a civil servant, was probably being all reasonable and dependable and useless, I’m sure. I could hear my name pop up every once in awhile in all their muttering and I could picture them sitting—Mr. Carter alone on the couch against the fake bay window and Mom and Dad sitting side by side on the fake velvet couch against the wall—drinking coffee with saucers they don’t even need, on coasters of Paris scenes protecting ugly little tables.

I hated that living room. Mom likes powder blue and rust. She likes the names of colours. She says “ashes of roses” for a horrible, pinky grey, and “rust” for an ugly, tacky orange, and “powder blue” for this colour that looks like the fluoride treatments they give us at the dentist. Our walls are “champagne” (dingy yellow), the indoor-outdoor rug in my room is “goldenrod” (muddy orange), and the fridge is “avocado” (shitty green). “And it doesn’t show the dirt” was how Mom described our new kitchen floor, which was putty grey and orange and brown in big squares with diamonds in it. “Great,” I said, staring down at it. “I can puke on it and you won’t be able to tell.” My brother Jerome sneered at me. He hated it when I spoke at all, let alone bugged Mom. Of course, Jerome was a boy, so he was Mom’s little darling. Mom’s happy little face got trembly and fierce. “You. Are. Miserable,” she said. “Miserable” as well as “negative” were her two favourite words to describe me. “Just miserable! You can go to hang!”

“Go to hang” were the worst swear words she used. “Hell,” I said.

“That’s it!” yelled my dad, who was normally a little slow and dense, but got mad really fast sometimes and had a really loud voice. I ran to my room.

So Mom and Dad and Mr. Carter were in the powder blue and goldenrod living room talking to each other, pretending, I’m sure, they didn’t know what I had tried to do. In my room, I could always hear everything in this stupid house. Hockey Night in Canada from two floors away, especially in the sickening new dark nights of winter, and I couldn’t watch a movie on TV because my brother wanted to watch hockey, so I’d stay in my room that I hate with goldenrod, indoor-outdoor doesn’t-show-the-dirt carpeting that nothing looks good with.

Jerome just grunted and played sports and smelled bad. I don’t think we’ve actually ever had a conversation once. I wished we were like those twelve kids in that old book, Cheaper By the Dozen, where their dad was always teaching them typing or taking them on trips or making them put on plays in “the drawing room.”

Once, I took Jerome’s table hockey game and ripped off all the little plastic guys and drew beautiful little ballerinas in tutus on cardboard and cut them out and then taped them to the little metal rods. Then I could have a ballet. Even if they couldn’t jump, they twirled pretty well.

I used to take ballet, but I stopped when I was twelve because I wanted to sleep in instead. The best feeling in my life was sleeping in. I could just lie there and anything I thought would come true in my head and the room would be all grey. My brother trashed the cardboard ballet. He didn’t touch me though. He never touched me. Nobody ever touched me. Even at school where I hung out with the retards and brains and dogs, no one ever, once, tried to hit me. Even when I walked Caroline “the retard” home so the cool guys couldn’t throw rocks at her and yell, brilliantly, “Retard,” they never went for me. I wished they would sometimes so I could kill them. I used to dream about beating them up all the time. I wanted to catch them torturing a kitten or a bird with their stupid BBs and shoot them with their own guns. I was thirteen when I realized that it wasn’t fair that guys got everything. I mean, they’re so stupid. Like, so stupid. How did it happen that men ruled the world?

Now that I was in Grade 7, girls were getting even dumber and boys were ruling everything. Suddenly, me and Edna, my best friend, and even Caroline, went from being normal kids who played with everyone else at recess to “dogs.” Except, I have to admit, Caroline was always a retard—well, slow. She could keep up with her age level just barely, but she had a good imagination, which is what I liked about her. I just wished her mom would not make her wear knee socks and ugly black shoes. That would make anyone look like a retard. At least even I got to wear cords and a T-shirt. Edna, who had frizzy blonde hair and braces, still dressed like she was twelve in matching little pantsuits.

In the cafeteria at school once, I overheard Billy Joe MacPherson, who used to be nice, but smokes, saying he was going to have a party. I was sitting at the table over from them, reading. Billy Joe said, “I’m going to invite one of the dogs to the party.” “Who? ” asked Patrick. “Edna, Caroline, or Marnie? ” I liked Patrick. Sometimes we ended up walking home together by accident. We were always put together in grade school because we always finished our work first. We’d compare our grades as we walked. O.K., it only happened once.

“Marnie,” said Billy Joe.

At first I was freaked that I was a dog, but, after all, Billy Joe did invite me, and I felt good about it. I went to the party even though Edna and Caroline were mad: “You’re just like them now.” A part of me I was ashamed of hoped it was true. I had already huddled out of the wind in the grey-concrete back doorway of the school, smoking with the cool kids, hungry and dizzy and trying not to look shocked when one of them dragged out a joint. I missed the bus home and walked through the scraggly fields and by the brown apartment buildings in the dead light of the suburbs, feeling dangerous and lonely. Caroline and Edna were at home drawing paper Barbie dresses and eating cookies. One of the cool girls, Connie, who looked like Chrissie Hynde, said “See ya” before I left, just like I was normal. Even though Caroline and Edna said Connie was conceited, Connie was funny and had a big mouth. Especially to guys. Gram’s romance books would say she was “feisty.”

Dad dropped me off at the party, which was near the school. It felt weird to drive by the closed school at night. I could picture myself in my class, bored and doodling, looking out the window and wishing the teacher would just die, or wishing I could jump out the window and run away because I had super powers. Maybe the ghost of my daytime self was in the class right now, looking at me driving by thinking about myself. That would be cool.

“Call and we’ll pick you up,” said Dad, as he dropped me off at Billy Joe’s little brown house. I went in and Billy Joe’s mom sent me downstairs. Everyone was sitting cross-legged on the floor and smoking. I sat beside Connie and said “Hey.” She was wearing too much mascara and blush, and looked like she thought she was Linda Rondstat. Supertramp, who I hate, with their stupid high voices, trying to be scary, was playing. Figures.

We played spin the bottle, except the guys just pointed at who they wanted and ignored the bottle. I was sure I was going to do something stupid and embarrass myself and nobody would pick me. The other kids kept looking at me out of the sides of their eyes. Nobody was even laughing or joking. They were so cool, you’d think they’d played spin the bottle since they were two years old. Patrick pointed to me and I went to the furnace room with him. I could see Connie. She was squirming all over Tommy Schneider. No way I would ever do that. I put my face up to Patrick’s and let him drool all over me basically. It was gross. I felt idiotic. Right afterwards I snuck upstairs without anyone noticing and went to the kitchen. Billy Joe’s mom was there and she gave me a cigarette. She was nice. “What a great shirt,” she said. I couldn’t believe she noticed. I only wore baggy pants and men’s shirts, but I always collected the best patterns and colours for the shirts. Dad always laughs when he see me in one of his shirts. He never gets mad. I think we have the same taste. Anyway, Billy Joe’s mom, who had a blonde perm and stretchy blue shorts, talked to me like I was a grown-up, and she even said I had nice hair. I left before anyone downstairs came up, and walked home across the field that separated Billy Joe’s rent-income neighbourhood from my house.

Whenever Mom says “rent-income,” it’s in quotation marks and she gets a look on her face. She doesn’t like Caroline because Caroline’s from the rent-income district. Also, Caroline has really big breasts and Mom probably thinks she does it on purpose, just to be tacky. Anyway, when I got home, I went to my room and lay on my bed in the dark. I was so relieved to be away from the cool group and their gross necking. Edna and Caroline were right. I never should have gone there to begin with, and now I wondered what they were doing. I swore I’d never talk to Patrick again. The memory of his slippery mouth made me want to scream. I lay on the bed and listened to the eleven o’clock news through the floors and the whoosh of the buses going by a street away. I stared at the patterns on my wallpaper until they changed shape.

The wallpaper was from when I was about eight years old and I refused to have those Holly Hobbies all over my wall. I did not want typical girl wallpaper. I was more into animals than Cabbage Patches. Maybe horses, I thought, because I was an animal lover. Mom didn’t want horses, so we ended up getting a rust velvet flocked wallpaper. The design is strips of ovals with curlicues in them, and the area over my pillow was quickly stained darker with my head leaning on it. Gross. The wallpaper is called “colonial.” When I’m sick, I stare at the curlicues in the ovals and they transform into little shapes like butterflies, ladies in old-fashioned dresses, and dogs howling.

I stared at the wallpaper and listened at Mr. Carter’s stupid fake laugh downstairs.

“It’s a very difficult time…puberty…so many changes.” My mother. I hate the way she says puberty. It always makes me think of pubic hair. And since Mom can’t even say the word “pregnant” without whispering, it’s gross whenever she says anything about sex. When I got my period when I was eleven, she looked like she had a toothache for days and turned red when she looked at me.

“Perhaps not getting enough of a challenge,” I heard Mr. Carter say.

Mr. Carter paid extra attention to Caroline and Edna and me because we were in the media club after school. I was just in it to hang out with my friends. I didn’t really care about cutting clippings from newspapers.

Mr. Carter was a total creep. He had long thin hair, all sticky, and was mostly bald and had these big, watery black eyes that always looked sad, and grey skin. You can always tell the pervs because they have grey skin. I used to babysit his two suck kids, Jennifer and Tod, sometimes. Once, when Jennifer and I watched Grease on TV, she jumped on me and grabbed my tits. She was only seven. What a weirdo. You should have seen Edna when she got to babysit for Mr. Carter. She looked all smug and insufferable. She had a crush on him, I think, but how could you have a crush on an old grey guy? Edna was getting really gross. Her bra strap was beginning to show all the time and she was getting this cross-eyed look on her face when she talked to boys—any boys, even the sucks we hung out with. It was stupid because she looked so dumb, with her frizzy blonde hair in pigtails and still wearing the clothes she wore when she was eight. Once I saw Mr. Carter and Edna alone in the media room. He was standing behind her with his grey sausage hands on her shoulders. I went in and sat down and he moved over to me. “I don’t want a massage,” I said.

“What’s the matter? Don’t you like to be massaged? ” he asked.

“No!” I said as mean as I could. Edna and Mr. Carter looked at each other and gave that little smile my mom does. They made me feel like a big baby.

Another time in the media room, Caroline was pasting a newspaper clipping of a kitten with a bowler hat on its head in her media scrapbook.

“’Fraid of heights? ” asked Caroline, a huge grin on her face.

“What? ” I said.

“Your fly is!” yelled Caroline, and whooped. It was her favourite joke. I did up my fly and sat down.

I knew I was turning totally red and my armpits were soaked. Mr. Carter noticed.

“You shouldn’t be ashamed of your body,” he said as he walked to his desk. I instantly felt awful. I didn’t like him talking about my body. Mom would say I have “a nice figure” in a strained way, like she read somewhere you had to bolster your teen’s self-esteem, but I thought my body was really ugly and she had to say that because she’s my mom. Anyway, I didn’t want a nice figure, I wanted to be skinny. Even when I changed in my room, I hid myself so no one could see how fat I was through the window. That’s why I wore baggy pants and my dad’s shirts. I wouldn’t be ashamed of my body if it was skinny.

“Are you ashamed of your body, Caroline? ” he asked.

Caroline stretched her thick lips into another grin. She had teeth, but it always looked like she didn’t. “I have a beautiful body,” she said.

When we were walking home, Caroline said again, “I have a beautiful body.”

“Yeah, don’t say that, Caroline. People will take it weird,” I said.

Caroline got her stubborn look. Just because people are stupid doesn’t mean they can’t have personalities. Caroline got really angry and stubborn at the weirdest things.

“I do.” She opened her arms. She stank. Someone was going to have to tell her about deodorant. “I have a beautiful body. Mr. Carter says so.”

The day I tried to kill Mr. Carter, it was hot, the second week of September. I was waiting for Caroline. She was late and the schoolyard was empty, not even any rent-income kids waiting to bug Caroline. Just me and the hot pavement, the yellow field by the school, and the birds with their late-afternoon chirps. I heard a sound like a car starting in the distance. Then, coming from the bushes, a loud moan like a science-fiction monster dying. The bushes were where the cool kids went to smoke cigarettes and even neck. They said a Grade Thirteener hanged himself there five years before because he was a drug addict. The moan definitely turned into crying, so I started to walk towards the bush. When I was almost there, and I was scared to go down the path, Caroline came in sight. She had her face all twisted and she was making this weird sound. There were leaves in her hair and her shirt was ripped open. I could see the ugly fat blobs of her boobs falling out of her grey bra. There was a big thorn in her leg with a long stream of blood coming down. “What happened? ” I asked. No answer.

“Come on, Caroline, I’ll take you home,” I said, but she didn’t even see me. I grabbed her arm and she shook me off. She kept walking, like Frankenstein, across the field to go home, making that sound. I followed her, really nervous that someone would see her boobs. We got to her house and her mother sent me home right away without even giving me a drink. It was a long walk home. I was dying of thirst. I wished we had a pool.

That was the theme of my life, listening to other people swim on a hot day.

Edna has a pool, but it’s totally wasted. Her gross little albino brother, Peter, never went in their swimming pool, but whined “I want to swim. I want to swim,” his skinny little white bones knocking together, but he wouldn’t even go in the water. He didn’t do anything about it and would just look scared. Mrs. Winchester, who is fat with a big red face, wouldn’t even get mad. She’d just say, “I know, honey.” I wanted to push Peter in so bad and tell him to just shut up, but Mrs. Winchester was a psychiatrist, so she’d think it was all traumatic if I pushed him, and I hardly ever got invited to swim in their pool, anyway.

The Carters have a swimming pool. We never got to swim in it. There’s also a swimming pool next door at the Neumans’ and behind us too. In summer, I have to hear other kids swimming all the time. No one ever invites us. We don’t have a pool. We rent a cottage for three weeks every year. It’s like our street, but on a lake. Two rows of five little cottage houses lined up on a lake with a wide street between them. It was only fun last summer because the Deacon boys from America were there and they took us water-skiing and we played cards with them and at night they smoked on the beach. Sometimes they were kind of creepy though, they kept asking me if I was eighteen and laughing at each other. I can see their faces half-lit by the bonfire. “Er yew eighteen? ” “Why? ” I’d ask. “Is it illegal to smoke? ” and they’d look away and down and laugh even sneakier. I later figured out that it meant they could have sex with me without it being statutory rape if I was eighteen, which apparently is a big thing in America. They’re always statutory raping each other. I guess Canadians just don’t. I’m eighteen now.

So, when we were not at the cottage in the summers, the story of my life was just lying in my hot room and reading and listening to the buses wheeze and whoosh by a block away, and to the neighbour kids scream and splash. I’d listen to the hollow rubber bouncing sound of the diving board on its springs. Wet feet land, “boi-oi-oing,” scream and splash. And then the bus would go by on the dry road behind us. Exhaust. I get bus sick on buses.

The adults were downstairs that day because I went to the Carters’ backyard after supper. I opened their side gate and saw Mr. Carter in the pool, listening to the radio. I went up to him and watched him swim. He had hair on his back. Black hair. Squooshy shoulders. “Marnie,” he said. “Come for a swim? ”

I threw his radio in the pool. I heard you could kill people that way. I ran away as fast as I could. I went to my room.