The morning after the very first night Hazel charged for sex, she decided to take the streetcar home instead of a taxi. She had been bought for four hundred dollars for a guy’s thirtieth birthday. She had asked for a bottle of tequila too, but this was Ontario, where you can’t get liquor late at night. She got the four hundred dollars in crumpled tens and twenties to sleep with a guy she was going to sleep with anyway. She didn’t even really like tequila, it just sounded daring.

“You know it’s his thirtieth birthday,” his friend had said in the kitchen, waggling his eyebrows suggestively.

“Four hundred dollars and a bottle of tequila,” Hazel said instantly. It had suddenly occurred to her that she had been steeling herself for sex without adoration. It was a familiar feeling. It made her feel lonely, sad, and ugly. It was bad enough when a guy she liked didn’t call, or acted like she wanted to marry him if she called him, but when a guy she didn’t even like didn’t call, well, that was just degrading. Somehow, she never managed to get to the hand-holding, brunch stage with boys. She was either sent home or deserted after mostly surprisingly satisfying clinches. It was bewildering. She was sick of it.

Hazel was a bookkeeper, a woman who constantly assessed value. Next to her fabulous glittery girlfriends, she was dogged and plain. That was her role. She saw it was clearly delusional of her to expect handsome, charming lovers with quick minds and warm hands. So, that night, she assessed herself for her worth in the marketplace.

At twenty-seven, Hazel was no beauty, but she was blond. Men liked blonds. When she walked into a room, she generated a stirring amongst the males. Being of medium height with a flat chest and chubby ankles, she knew it was her blond hair that caused this stirring. She was well aware that if she were a four-foot-two-inch troll, as long as she had blond hair, she’d still be in the running. Millions of mall sluts and trophy wives couldn’t be wrong. Hence, she dyed her hair grimly every month, her only purchase in the slippery mud of sex appeal. The dykes at the art gallery where she worked didn’t approve. She was a very good feminist in all other respects; it was a prerequisite for working at the government-funded gallery.

Hazel took the streetcar that Sunday morning at five-thirty because, for the first time in her life, she felt leisurely and in control the morning after, a feeling completely due to the four hundred dollars in her purse. No scurrying home like all those other women who take those guilty dawn cabs. If you pulled back in a crane shot and made them all little lights, you could follow them, criss-crossing through the city. If you looked closely, you could see faces carefully applied the night before, now stale. You could see that one cowlick they almost sobbed over, now hidden in a mat of bed head. There they are hunched in the taxis, smeared with dirt and booze and cum, and wondering if they’ll ever see him again, if this ruins their chances with the one they really like. No more cabs of loathing for Hazel.

Hazel also loved to savour early mornings and their pre-rush-hour calm. She walked to work early in the morning, when there was no one on the streets to compare herself to. The shy light of the new day made everything look like a carefully composed photograph, even ugly hydro poles and Coffee Times. The streetcar carried her like a queen in her litter, past the cheering storefronts.

Hazel understood why the rumpled girls didn’t take public transportation early Sunday mornings. You had to be strong to face crackheads with sliding mouths and eyes; to travel with people whose mothers had let them go outside without mittens in hard winters. Hazel felt strong.

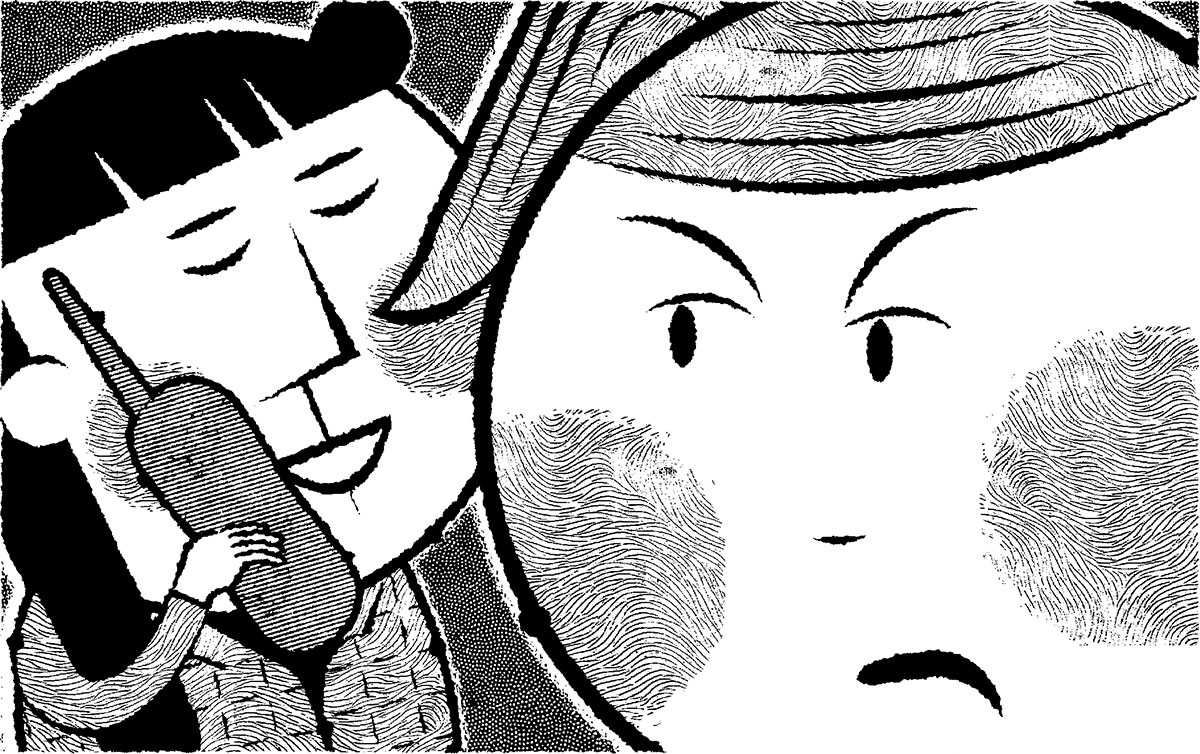

A young woman with swinging black hair and a puffy mushroom ski jacket walked down the aisle, talking loudly into her cellphone, her brain stuck in a neural ditch of “ohmygods” and “whatevers.” A stray, middle-class schoolgirl who lied to her parents about a slumber party.

“O.K., so now my favorites are Tristan and Scott,” she gurgled. “I went to Scott’s place last night. Likeohmygod—you told me York Mills was nice, but ohmygod. He made me leave when his girlfriend called up though. Man, am I hungover. Ohmygod, he’s so cute! Can you like two guys at the same time?”

The girl walked by and sat down across the aisle from Hazel. Hazel turned to look at her, but puff girl casually looked out the streetcar window as she talked in her penetrating voice. She did not mark Hazel’s ire. In a feat of indifference Hazel wished she could muster, the girl kept talking loudly, her fat face composed in a teenager’s blank approximation of a Gap model’s: broad and stupid with a carefully drooping lower lip.

Hazel felt an unfamiliar smugness. At least she got paid. Emboldened by her status as a professional, she glared at puff girl. Didn’t this fresh-fucked child know she had just been a piece of Kleenex because some rich boy’s parents weren’t home?

The car stopped in front of the mental health centre, the windows mutely suggesting a view worth looking at. It was a horrible grey prison in no way fooled by the nursery school landscaping, which was punctuated by black, wooden cut-outs of humans. A few sick, stalked by the silhouettes, were out in the little courtyard near the front door.

Two young men with pale faces pretended to drop kick each other, like kids do. But they scared each other and backed away after every kick, making placating gestures with their hands. They were smoking. On another bench was a swish old lady in a smart, red coat. She was eating a sandwich. Stiff with arthritis or disapproval, she got up and put her wrapper in the garbage can. A tall man stood off to the side, a foolish look of satisfaction on his face as he drew on his cigarette and looked at the spring sky.

“I think he’ll call. Do you think he’ll call?”

It was unbelievable how loud this girl was. “Oh, and ohmygod, I looked so good. I wore the indigo boot cuts and my yellow top with the tie in the back? Yeah, like, and you know what he said? Guess what he said? He said, he said, ‘You look nice.’”

She squealed.

At the squeal Hazel had had it. She got up to get off the streetcar. It was like a stupid-girl infestation. You finally stopped being a stupid girl and you were surrounded by them.

Getting off the streetcar, her way was blocked by two fat, old men, identical in their baldness and girth, barely able to walk. Their pale-blue eyes bulged, their noses were potatoes, and their lower lips hung grotesquely, almost to their throats. Halloween Gap models. Twins. They were twins. They shuffled slowly toward their seats. Hazel began to get mad. This was too familiar, trying to get away from being ignored and having to wait in line to do it.

Hazel turned around and marched over to puff girl, who was still bleating away.

“Would you please shut up? Everybody on the streetcar is not interested in your stupid love life.”

“Fuck off,” the girl said instantly, her clear brow barely furrowing. To the phone she said, “Some freak is telling me to get off the phone.”

“Look,” said Hazel, “nobody cares about this Scott guy, he obviously fucked you because you were there and he was drunk. He’s not going to call, and, although I can’t really say in all honesty that you deserve better than this, I’ll give you a hundred dollars to stop using the phone now. You can always remember that tonight wasn’t a total loss.”

The girl looked at Hazel, her cinnamon-frosted mask sliding into the face of a sad child and back again. But, dreaming no doubt of an even more subtle variation of her boot cut indigo jeans to seduce the boys with, she took the one hundred dollars and put the phone in her pocket.

“And turn it off!” commanded Hazel. Puff girl took her phone out again and turned it off, then turned her face to the window. Hazel went back to her seat and the streetcar lurched forward. She wondered who her next client would be.