This is the story of a child. He wears brown mittens. With mittens he burrows his way up out of the sand and then he is on the beach and the sun makes his eyes feel like eggs in a frying pan. He shakes the sand out of his hair, and what he’s unable to shake out, the breeze looks after. He wears a T-shirt with a picture of a superhero on it, a blond man in red long johns whose limbs stretch for kilometres in every direction.

You asked what the child’s name is, but I don’t remember. But he emerges just like a hermit crab, and so I’ll call him Herman, like Herman’s Hermits. Listen to the hiss. It comes from the lake, whose weak little foamy waves wash up almost to Herman’s feet. He cups a brown-mittened hand over his eyes and peers around him, turns in a full arc like a compass, the direction kind or the circle-drawing kind, it doesn’t matter. The beach is nearly empty. In the direction of the nuclear plant, four little dots are prancing. A mother dot, a father dot, a child dot, and a dog dot.

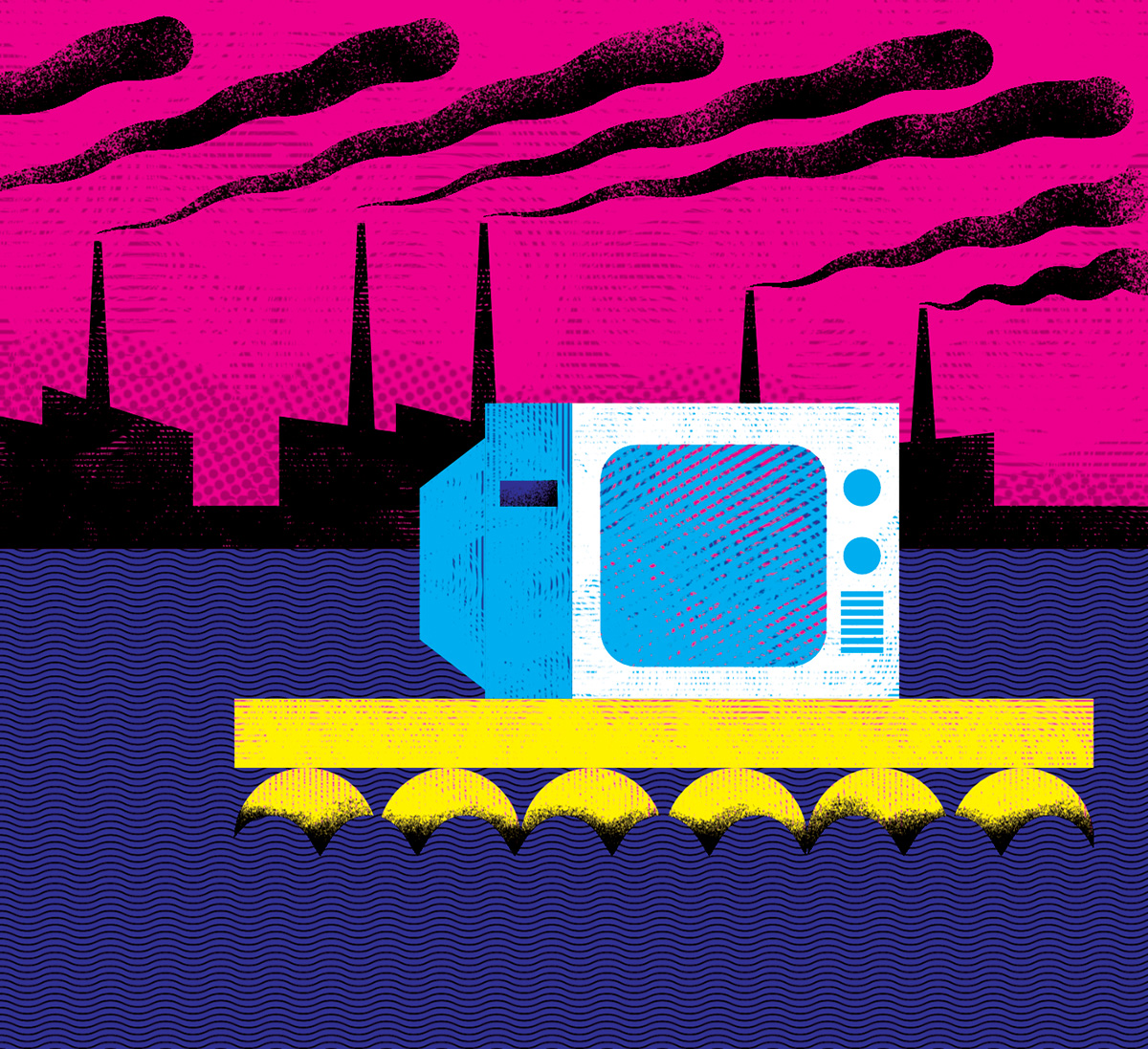

Herman hears the faint chime of laughter. He turns toward the lake now. Something is upon it, far in the distance. A fish, a boat, a piece of driftwood. Herman uses his super eyes to zoom in. A television on a raft. On the screen is a cartoon penguin carrying an attaché case. He’s on his way to a business meeting. Smokestacks leap into the air around him, pierce the sky, bellow great clouds of grey and black and red.

Herman reaches into the hole he just climbed out of and feels around for his lunch box. It is tin. It depicts Roy Rogers. He yanks it to the surface, and suddenly a girl is standing beside him, her shadow draped over his doughy face.

“Are you the child dot I saw a minute ago?” asks Herman.

The girl nods. She recognizes Plastic Man on Herman’s T-shirt. Then she looks out toward the lake. She points with a mittenless hand. Herman admires her slender fingers, the chipped yellow polish crowning each digit. “There lies Rochester,” says the girl.

Herman follows her fingertips across the water. A dark funnel stretches from the horizon into the sky, sweeping slowly across the most distant point of the children’s field of vision.

“What does it contain?” Herman asks.

The girl brushes sand off the front of her clam diggers. She lifts a red sippy cup of orange juice to her lips, treats her thirst.

“The inky roiling smoke of the ’nado contains a multitude of mouldering plastic shopping bags; several ecstatic chihuahuas; an oak desk with a chartered accountant, a pencil behind his ear; a Kenny G CD case with the CD missing—”

“The CD’s always missing!” Herman karate-chops into her sentence.

“—hundreds of photographs of dead relatives; a hailstorm of frozen peas, ricocheting off everything else; and our future. Any aspiration you may have, Plastic Man, is knotted into that limping angry ’nado.”

At the mention of his name, the Plastic Man on Herman’s shirt begins to tremble and then glow. Herman feels his belly become warm, and the warmth radiates through his shoulders and thighs, heading at freeway velocity toward his pudgy extremities.

Tentatively, Herman reaches out one hand, toward the lake, toward Rochester, and his hand keeps going and going. The girl dot bites her lips. Has she found the Saviour? Is she the Saviour, bestowing new powers among the ordinary men who walk the crippled earth?

“This is so weird,” Herman whispers as his arm stretches farther and farther across the lake, until he feels a weather event nipping at his strained knuckles. His fingers begin to snake from his hands, and soon they tighten around the throat of the dark funnel over Rochester, and there they remain, holding on for dear life.