My brother, Anders, had been with us for just two days, but already Larissa was complaining about the smell.

“He smells like a goat,” she said. “It’s like we’re keeping a herd of goats in the living room.”

“O.K., O.K.,” I said.

“I mean, it’s everywhere. The carpets, the curtains. It’s seeped into the fabric of the couch.”

“I know, I know, I know, I know.”

For most of the two days, Anders had perched in a chair at the kitchen table, rolling cigarettes and staring dreamy-eyed into space. He was very quiet. Were it not for the smell, you’d forget he was even there. But Larissa found him unsettling. Part of this, of course, was his appearance. He had confused blue eyes, broken teeth, and drifts and stacks of pale yellow hair; it gave him the look of a demented baby duck. And he rarely slept. At four in the morning you could get up and go to the kitchen for a glass of water and there he’d be—smoking a cigarette and leafing through one of Larissa’s Women’s Health & Fitness magazines.

“Please, Chet. Get him out of the apartment.” A lock of Larissa’s hair came loose from her ponytail; it floated above her head like a question mark. “And keep him away until the place has a chance to air out.”

“I said O.K.,” I said, hoping that would be the end of it.

I took him to the car wash, the hardware store, the pet-supply store, the electronics superstore, the coffee shop, the library, the movies, and bar after bar.

It was on the patio of the Eclipse that I found out the reason for Anders’ visit. “I’m meeting a woman,” he said.

Over in the corner, a chair scraped back, and then another, and then another, as a party of pink-faced businessmen paid their tab and left.

“What kind of woman? ” I said.

“Just a regular woman.”

“You mean, as in a date? ” This was a rare and amazing piece of news.

“I guess you could call it that.”

“You’re on a date,” I said, working the information over in my mind.

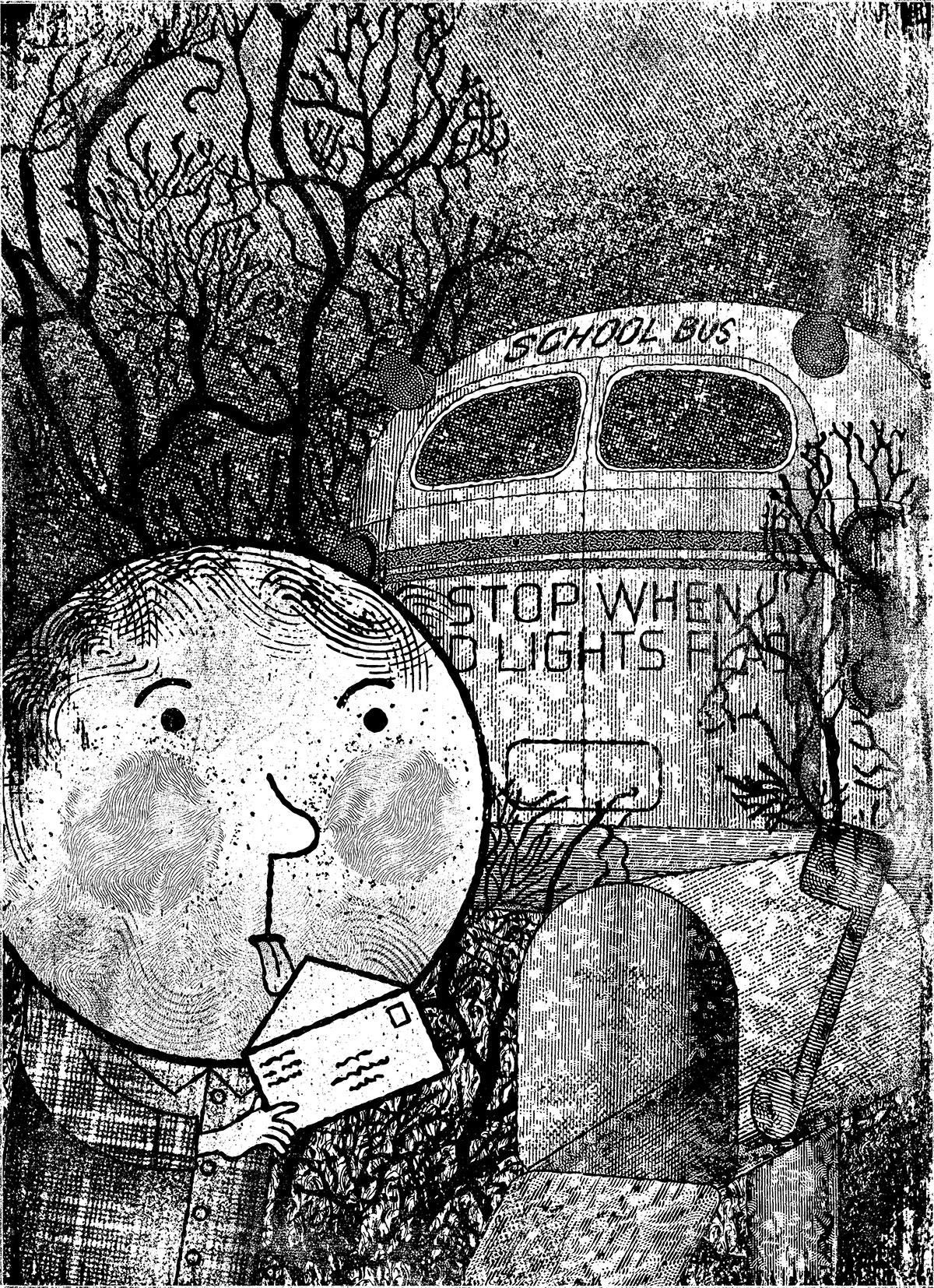

Anders lived in a derelict school bus on a scrubby tract of land in the Ottawa valley. There isn’t a whole lot of talent in a place like that. His last girlfriend had been a Wiccan pot farmer who’d led him on just long enough for him to drywall her cabin. But at least she’d been single—the one before that had been fifty-eight years old and long-married. My brother: twenty-eight. When her husband found out about the affair, he paid a visit to Anders’ school bus and knocked out two of his teeth with a Coleman flashlight.

“Tell me about this woman,” I said. “Where’d you meet her? ”

Anders took a sip of beer, wiped the foam from his lip. “Ummm,” he said.

“What does ‘ummm’ mean? ”

“It means I don’t want you to judge.”

“When do I ever judge? ”

“You always judge,” he said. He looked around to see if anyone was listening, but all the tables were empty. “I met her through the mail.”

“This is beginning to make more sense.”

“See? You’re judging already.”

Anders zipped up his jacket and crossed his arms. The day had been partly warm and partly cool. In the shadows you could still feel winter; in the sun it was all bird’s nests and crocuses. And the air! The air felt like it had been locked away for months in some dark riverbed. It smelled muddy, fertile. Full of waking things.

“I just think you need to be careful of mail-order brides,” I said. “They’re mostly Russian hookers trying to get citizenship. You can pick up some vicious fungal infections from Russian hookers.”

“She’s not a mail-order bride. She’s a…She’s a…regular woman. She took out an ad, and I answered. We’ve been writing back and forth for a year and a bit.”

“So she’s your pen pal.”

“Yeah, sort of, I guess.”

“What does your pen pal do? ” I said.

“What does she do? ”

“For a living.”

“Ummm,” he said.

I see it in him. I see it in the way he holds his cigarette, the way he sits in chairs, the way he talks: I see me. Because I’m seven years older, and I’ve had some influence, you know? I see my mother’s lunacy, sure, and my father’s Nordic solitude, but mostly I see me. It makes me feel responsible. It makes me want to take care of him, because the poor bastard sure can’t do it on his own. I throw him some work when I can. In the warm weather he’ll come down south for a few days and work on my crew, laying expansion joints, tearing up old parking ramps…whatever. In the cold weather he’ll spend weeks at a time up north by himself. He’ll make beeswax candles to sell to cottagers. He’ll get bored and experiment with explosives. And, apparently (this was a new one for me), he’ll sit around writing love letters to women he’s never met.

“She’s currently pursuing some interesting opportunities,” Anders said. “Trying to turn her life around, make a fresh start. That sort of thing.”

“Uh-huh,” I said. “And why’s that? ”

“Because she…” Anders scratched his head, coughed twice, and picked at something on his knee—anything to avoid my eyes. “Because until recently she spent some time in a federal penitentiary.”

What could I do but laugh? “And why is that? ”

“She stole some money from an old-age home.”

“You don’t say.”

“At knifepoint. But,” he added, “she admits her mistake.”

I had a swig of my draft, and then another, and lit up a smoke, and considered my fingernails, and stared off at the fragrant, peaceful sky. “Well,” I said, “all things considered, she sounds like a step up for you.”

“She is. She really is.”

A new woman, a new start—it sounded pretty good to me. Someone who’d love you for all the wrong reasons. Someone who wouldn’t identify and exploit your every little weakness. It sounded pleasant.

I took a hard look at my brother. He was wearing an old blue plaid shirt and a pair of filthy army pants. His hair was mushed up on one side of his head, and his face was covered with a week’s worth of glistening blond stubble.

“You can’t go on a date looking like that,” I said.

“Why not? ”

“Because you look like a felon. Bad analogy. But you see what I’m saying.”

“No.”

“You look like you’ve just spent three months in the bush.”

“Well, but I have.”

A tiny brown sparrow fluttered down to our table, eyeballed me critically, and fluttered off again. “But that’s not appropriate in your dating-type scenario,” I said. “It’s unappealing.”

“So what am I supposed to do? ”

“Buy a new wardrobe.”

Anders slumped in his chair, his face slack with desolation. “Really? ”

“A new shirt that’s not frayed in the cuffs. A new pair of pants that’s not covered with food stains and bloodstains and…and whatever that is on your thigh. There’s a flower in you, and it’s just waiting to burst out.”

“Couldn’t I just—”

“No. And then you’re going to need a shave. Why? Because a good shave sends a signal. It tells the woman you care about your appearance. It lends you the illusion of being further from rock bottom than you really are.”

Anders ran a hand across his cheeks. His eyes were red-rimmed and shiny; he looked like he might start to cry.

“And lastly,” I said, “and most importantly, you need a bath.”

It was like I’d waved a rifle at him. He flinched, raising a hand to his head in a protective gesture. His face was full of pain, defensiveness, and, mostly, panic. If he’d gotten up and run away I wouldn’t have been surprised.

“I just had a bath,” he said.

“When? ”

Anders eyed the front gate, the back gate—all the escape routes. “Why do I need a bath? ”

“Have you smelled yourself lately? No woman wants to become intimate with that.”

He raised the sleeve of his shirt to his nose and inhaled. “I smell good,” he said. “I smell like woodsmoke.”

Our waitress came out onto the patio with a fresh ashtray.

“Hannah, Hannah,” I said.

Hannah was dark-eyed and almost pretty. She had long brown hair that she wore in fetching arrangements. And although I knew her only in her professional capacity, she seemed like she was a sophisticated and socially adept kind of person who could give us a lot of valuable feedback.

“Yes, darling? ” she said, picking up our old ashtray.

“Do me a favour, would you? ”

“Anything.” She set the new one in front of me.

I pointed at Anders, sitting there with his stunned-deer look. “Smell my brother,” I said. “Smell my brother and tell me what you think.”

I try to be patient. It’s not Anders’ fault, the way he is. Defective D.N.A. travels through our family like a bad case of lice.

Our mother, for instance.

Mom was never entirely steadfast and rational, even when we were kids. There were always long summer afternoons in bed with the shades drawn, a damp washcloth on her head, As the World Turns on TV. There were always manic cleaning episodes: on her hands and knees, scrubbing floors till her hands turned the colour of raw pork. But, on the bright September day, twenty-odd years ago, that she discovered our father screwing the next-door neighbour, Mrs. Bridges, on our rec-room sofa, something in her head unspooled. It was a memorable day, though I don’t remember much of it. I remember the screaming and crying, the slammed doors and thrown porcelain, the phone calls to the police—and then, suddenly, an eerie quiet.

She kicked Dad out, of course, and soon after filed for divorce. The real trouble started a couple of years later, though. The real trouble started when, flush with alimony and a bottomless pool of spite, she decided to realize her life’s ambition and become everything my father despised: a dealer of fine collectibles. That was the beginning of the long, slow slide. Because as soon as she got hold of, say, a Victorian watering can or an art deco snuff box or some other piece of dusty, worthless crap at an auction or estate sale, she couldn’t bear to let it go. It was too valuable, she said. Too precious to go into the homes of whores and libertines. And so she put it all into cardboard boxes and stowed it away, and the boxes accumulated, and Anders and I watched as our childhood home slowly filled, floor to ceiling, with junk.

“One day I’ll pass all of this along to you,” she told us.

I had no doubt she’d make good on that threat. All those mouldy old boxes, full of stuff that belonged to someone else…It’s why I got myself snipped. I was determined not to pass that crap along to my own kid—my own sweet, innocent, theoretical child, who, had he actually existed, would’ve never asked to be born.

“You look terrific,” I said. “You look like a new man.”

It was two days later. Anders was standing in the kitchen, submitting himself to our examination. In two days a miracle had occurred—a miracle of good taste, hard work, and organization. The man in front of us was clean-shaven and freshly bathed, wore a fashionably cut pair of jeans and an expensive blue shirt, and sported a flattering haircut, moderately gelled.

“Who knew? ” Larissa said, scratching her cheek.

“Just one more thing,” I said, “and the makeover will be complete.”

I rushed into the bedroom, grabbed a bottle of cologne, and, before Anders could protest, sprayed some just above his head, so that a fine cloud drifted down on him.

“Why’d you do that? ” he said.

“Because,” I said, “cologne, like a good shave, sends a signal. It tells the party in question that you’ve taken care to smell nice. And if you’ve spent all this time trying to smell nice, it means you’ve probably taken the time to wash out the crack of your ass.”

It was twenty minutes to six. Anders had arranged to meet his ex-con at six o’clock. They were having fish and chips at Neptune’s Cove, on King Street. I walked him down there in case he needed some last-minute advice.

“Whatever you do,” I told him, “don’t talk about Mom and Dad.”

“Uh-huh,” he said.

“And try not to talk about your school bus or anything involving candle-making. Or that incident with the dynamite—that was just embarrassing. And if the subject of ex-girlfriends comes up—”

“Yes, yes, yes.”

“But do try to find out about life in prison. I want to hear about that.”

It took ten minutes to get downtown. Anders and I walked along in silence, down cracked sidewalks and buckled roads, the last of the sunlight making the sky go pink. Then, a block from the restaurant, he stopped. A warm spring breeze gently raised and lowered the flaps of his shirt pockets. He regarded me with great urgency.

“I don’t need you to walk me to the door,” he said. “I’m not some fucking baby.”

He spun around and walked the final few steps to Neptune’s Cove. There was a cockiness to his stride, a vanity to his bearing. And I’m not afraid to say there were tears in my eyes. Every doctor wants his patient to thrive, and I was no different. I’d done the major surgery. The rest was up to him.

To my way of thinking, it’s better to indulge your vices and live a short, noteworthy life than to shy away from everything fun and turn into a sickly, neurotic freak like so many of my friends and family. And maybe, yes, you spend too much time at your local pub, drinking with your buddies, and not enough time at home, talking about your feelings with your girlfriend, but if you don’t take time to nurture yourself, how can you take care of anyone else?

That’s why, after I delivered Anders at the restaurant, I popped in for a quick beer at the Eclipse. Larissa had told me to be home by seven. She wanted us to have a quiet dinner together, just the two of us, and I had every intention of being there, I really did. But Hannah was working that night, and the usual crew was sitting around the bar, and by the time I checked my watch, three hours had gone by.

“Oh shit,” I said.

Hannah was at the cash, ringing in someone’s tab. “What’s up, Chet? ”

“I’m two hours late for dinner.”

“Shall I ring you out? ”

“Nnnn…I’d better just stay here till she’s gone to bed.”

Hannah counted out some bills and laid them on a little plastic tray. “That’s a fantastically bad idea.”

“On the contrary, I thought it was pretty good.”

“Go home,” she said. “Take your punishment like a man.”

I pretended to consider her advice. “All right. Sure. I’ll go home,” I said. “Just give me one more pint. For, you know, courage.”

Because, after all, what did Hannah really know about my relationship with Larissa? She knew what I told her. She didn’t know it had devolved into a state of absolutes, of alwayses and nevers: I always left my underwear on the floor; I never emptied my ashtray; I always left the margarine out; I never flushed the toilet. She didn’t know about the long silences, the nights on the couch. She didn’t know about the screaming fights. I’d changed, Larissa had said. I wasn’t the person she’d fallen in love with.

I left the bar around two, profoundly shit-faced, but managed to steer myself home. I stumbled down mucky spring sidewalks, past darkened houses and thrumming electrical boxes. The night sky smelled of birth. The trees were erupting into bloom. I soaked it all in and, for a while, forgot about my troubles. Forgot about Larissa. Forgot about Anders. It wasn’t until I reached my front stoop, checked my pockets, and realized I’d left my keys on the kitchen table that the troubles all came flooding back.

“Oh no,” I said. “No, no, no, no, no, no.” And I kept saying it, over and over and much too loud, until the words resolved themselves into an understanding and, finally, into a plan of action.

The only way in, I realized, was to break in. This made sense at the time. At the time it seemed perfectly correct and reasonable.

I went around back, rifled through the garage, and pulled out the landlord’s wobbly aluminum stepladder. We lived on the second floor; if I placed the ladder under our deck and stood on the top rung, I’d be able to grab the top of the deck’s railing and pull myself up.

That was the plan, anyway.

I fixed the ladder as soundly as I could and climbed it as carefully as possible. I reached the top rung, yes. But I was drunk, I was very drunk. So, when I reached for the deck, my foot slipped. My foot slipped and then my legs gave out from under me and then I dropped, slow motion, to the driveway, where I heard my right arm make a sound like a snapping branch, and felt the asphalt cool against my skull.

I blinked—twice, three times. Up in the sky I saw clouds, stars, jet trails. People in flight from one place to another. Then the world dropped away and I was swimming, swimming.

“I can’t believe we did that,” Larissa said, her voice fluttering with excitement. “I think maybe you’re the coolest guy I’ve ever met.”

“How many guys have you met? ”

“Five. No, sex,” she said. Then, catching herself: “I mean six.”

Larissa buried her face in her hands, her body heaving with laughter. When she took them away, her face was the same shade of red as her lipstick.

“Oh, God, I wish I hadn’t just said that.”

The train was swaying gently as it shuttled through the darkness. And we were swaying with it, side to side, bumping softly together, our skin sticking whenever we touched. Outside the windows there was nothing but black countryside, our faces reflected against it. The wheels clack-clack-clacked against the track. It was our first date, eighteen years ago. We were on acid and in love.

“Can you imagine what it would feel like to fall all that way? ” Larissa said. “The lights of the city spreading out below, and you just, just…”

“Bad,” I said. “It would feel bad.”

“But bad and great at the same time.”

An hour before, we’d been at the top of the C.N. Tower. We’d taken the train to Toronto, taken the elevator up the tower, marvelled for precisely ten minutes at the pretty lights, and rushed back down to take the next train home.

It was a two-hour trip each way, and we laughed the entire time. Some of this was the acid, of course. Some of it was the stupidity of what we were doing. But most of it was relief. Relief because we knew we’d finally found it: a person who’d love us without judgment. A person who’d love us for who we really were.

“Chet? ”

“Mmmm.”

“Chet? Can you hear me? Are you O.K.? ”

“Ggguuhhh.”

“Chet? Chet, baby? Oh, God. Are you, are you—”

“I had the. Best dream…”

“What is it, honey? Did you say something? ”

“I nnnneed…”

“Need? You need something? ”

“Just need…Just need two wooden spoons…”

“Why do you need spoons? ”

“Two wooden spoons and. A tea towel. For a. Splint.”

“A splint? Is there something wrong with your legs? ”

“I think. My arm is. Broken a. Little bit.”

“We have to get you to an emergency room.”

“I’m O.K. I’ll. Be O.K.”

“Really, though. We have to get you to emergency.”

“No. Way. I’ll fix it my. Self.”

It’s interesting—the knowledge that something’s gone badly wrong inside you. And it is knowledge—bodily knowledge. It focuses the mind. It amplifies the senses. Wind chimes in the distance, the rustling of leaves far overhead, the squealing of tires down the block—they sound like they’re an inch from your ear.

I was in bed. My own bed in my own room. It was morning. I could tell it was morning even though my eyes were closed. I could tell from the sound of birds chirping in the yard and from the light that came in through the windows and turned the backs of my eyelids pink. It was going to be another beautiful day. I could tell that, too.

I opened my eyes and looked down at myself. The sheets were covered in blood. My arm was wrapped in a tea towel, with two blood-soaked wooden spoons sticking out. I gathered that at some point I’d fashioned myself a splint—it seemed like something I might do—but I had no memory of it.

“Larissa? ”

The sound of running came from the hall, and soon Larissa entered the room. “You’re up,” she said.

“Uh-huh.”

“Anders is going to drive you to the hospital.”

“Yep. Sounds good.”

She came over to the bed and sat down. There was a time when I’d looked at her and all I’d seen were sparkles. But now all I saw were puffy eyes, a creased forehead. She looked tired and worried and I was seized with the profoundest guilt: I hoped I hadn’t done this to her.

“I’m sorry,” I said. “I’m really sorry.”

She seemed to understand what I was trying to tell her. A swirl of hurt and anger passed across her features and, for a second, it looked like she was going to say something—probably something she’d been rehearsing all night. How she’d wasted her youth on me. How I’d jackhammered her life into little bits. Instead, she cupped my cheek in the palm of her hand and kissed me on the forehead. “You piece of shit,” she said. “Can you move? ”

The answer was: barely. I could move slowly, painfully. I could move even though every movement seemed to damage me a little bit more. And so I travelled from the bed to a nearby chair, from a nearby chair to a kitchen chair, from a kitchen chair to the front door, and, finally, from the front door to the driveway, where Anders sat behind the wheel of my idling pickup.

I slumped in the passenger seat—unwashed, hungover, most likely concussed—and waited anxiously as Anders began to back the truck onto the street.

“Why a ladder? ” Anders said. “Why didn’t you just knock on the door? ”

“There’s a car parked behind you.”

“I see it, I see it.”

He jerked the truck to a halt, then carefully started to back out again.

“I didn’t want to wake her,” I said.

“Why didn’t you call and tell her you’d be late? ”

“Please shut up.”

It was a short drive to the hospital—but everywhere was a short drive in this little city. On the way I made Anders stop at a variety store for a pack of cigarettes. It was, I surmised, going to be a long wait in Emergency. After that we detoured east, to a Portuguese bakery that sold the most unbelievably airy, buttery crescent rolls I’d ever tasted, and a wide selection of exotic cheeses.

After this second stop, Anders hopped back into the truck, made a theatrical sniffing sound, and said, “You smell like a bar.”

“Do I? ”

“You should have splashed on some cologne before you left the house.”

“You’re hilarious.”

I cracked the window to let some air in and stared for a few moments at the streets, the sidewalks. Larissa was going to leave me. I could feel it in my stomach, in my balls. She was going to leave me and find someone boring.

“How’d your date go? ” I said.

“Not bad.”

“What’s she like? ”

“A lot bigger than in her pictures,” he said. “She was, like, a giantess.”

“Mmm. Bad genes.”

“And she has kind of a gravelly voice and a lot of tattoos.”

“She sounds, ummm…”

“And she collects dolphin figurines.” He thought about this, then shook his head in amazement. “Which I suppose you wouldn’t expect.”

We motored down Wellington Road. Ugly southwestern Ontario architecture whizzed by on all sides. There was no snow or darkness, unfortunately—nothing to hide under. The sunlight exposed every last brick.

“So do you think you’re going to see her again? ” I said.

“Maybe tonight.”

“Tonight! Wow! Then I guess it went well.”

“It went well,” he said.

“I guess my advice helped.”

“No. It went well in spite of your advice.”

One moment you’re a successful concrete-protection contractor. Someone whose opinion is sought. A tastemaker, a counsellor. A man of confidence and dash. The next, you’re battered and fucked and your misfit little brother, a person who’s always depended on you, a person who’s missed out on so many fundamentals, is shepherding you to the hospital, taking care of your most basic needs. You look like the same guy, but something has changed. The old you has cracked open. Something new is pushing out.

“Something new,” I said.

“What are you talking about? ” Anders was smoking while he drove, eating a crescent roll while he smoked.

“Did I say that out loud? ”

“You said something out loud.”

“I was just thinking,” I said.

“You were gesturing and making faces, too.”

“I have some things on my mind.”

“You better not do that in the hospital. You’ll scare the nurses.” The nurses, yes. I pictured the nurses: a bunch of huge, tattooed women in white uniforms. They carried stainless-steel trays covered with drugs and knives. “I wonder if they still give sponge baths.”

“Who? ”

“The nurses,” I said.

A sponge bath, a shave, a comb through the hair—these were things that told the world you were doing all right. A dab of fragrance, a change of shirt—they made you feel almost halfway normal. Not that there was any hope for me. My problems ran deeper than that. My problems required X-rays and I.V. drips and titanium rods drilled through bone. And even then: no guarantees. Fixed or broken, I’d be discharged. Spat up and expectorated. I’d be back out here with the rest of the wounded.