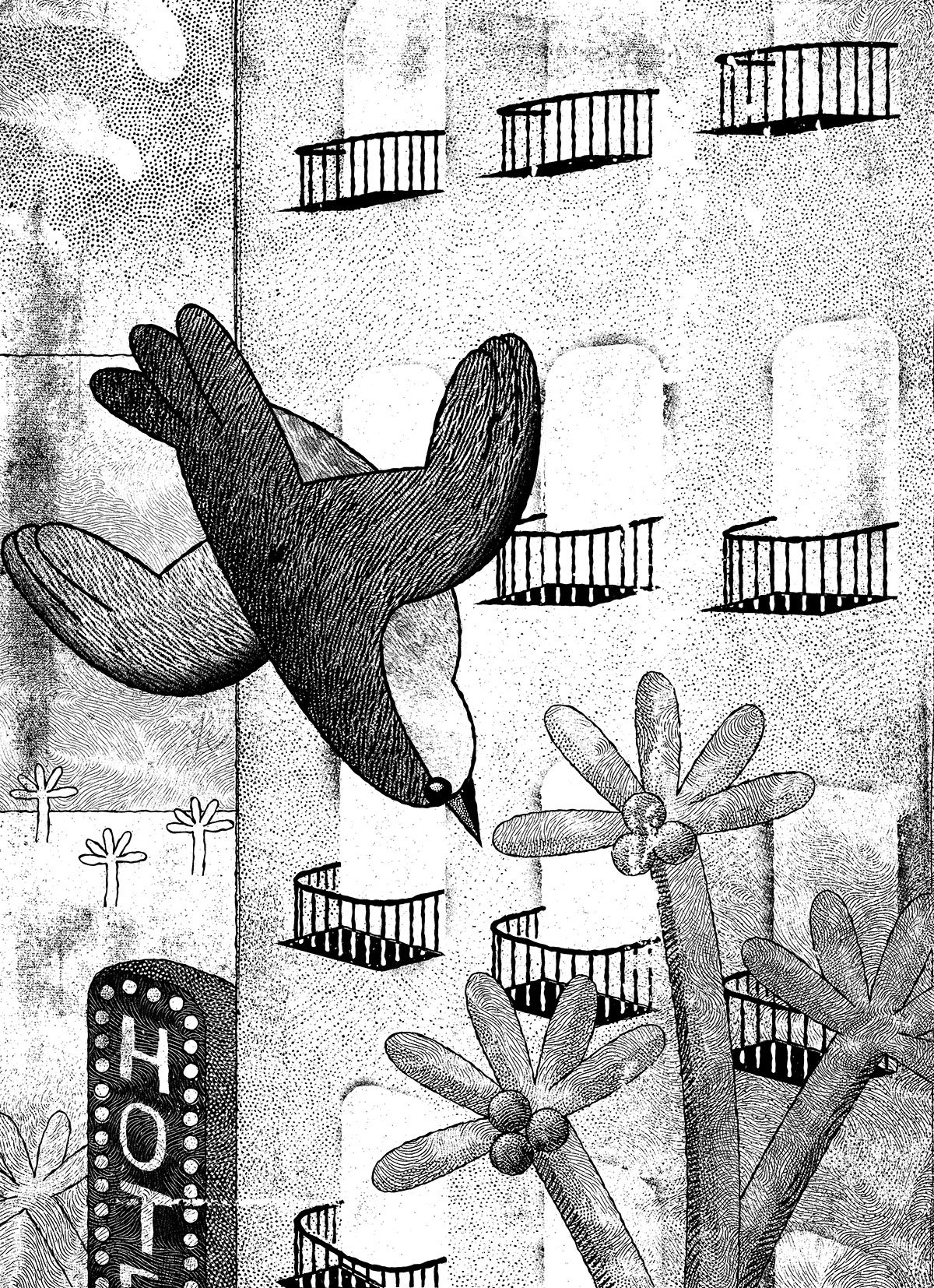

My name was Robin. Yep. That was my name. And this is what happened. I slipped, and then I fell. The first thing I thought: I’ve slipped off the balcony. The second thing I thought: it’s seven storeys down.

The air was wet and heavy, the sky a hazy blue. You’d think it would’ve held up a little thing like me, but no—I dropped. The palm trees were swaying, their leaves waving up, waving down: bye-bye, bye-bye. I saw them as I torqued and twisted through the air. Low black clouds were massing on the horizon. And I could still taste the corn dog I ate for dinner. The mustard, the cornmeal, the all-beef frank.

And what happens to your mind when your body can’t contain it any more? Half an hour ago, a guy named John Milton drank lemon gin from my navel. I’d known him less than a day. He came to our hotel room with a friend, a man he called the Goat. The Goat brought a movie camera. John Milton brought a knapsack full of liquor.

“So why are you called ‘the Goat’? ” I asked.

“Everyone calls me that.”

“Yes, but why? ”

“Fuck, I don’t know.”

“But there must be a reason. You don’t look like a goat. Do you act like a goat? ”

“Fuck, I don’t know. Body shots, anyone? ”

Hip hop playing on the radio. Muted pictures on TV. Someone was giving a speech. Maybe the president, maybe the pope. I really wasn’t watching. Kaytee lay on the bed and the Goat filled up her belly button. Then I did the same. I lay down on the bed. John Milton tilted the bottle. And when the lemon gin hit, it was cold, cold

First I saw the sky, and then I saw the ground. First I saw the sky, and then I saw the ground. And here I had to calculate…would I fall into the pool, the chlorine-blue, egg-shaped pool, or would I hit the flagstones? Either way, death was certain.

I wished I were home. I wished I were home in my room, with my bedspread and pillows. With my stuffed animals huddled on the dresser. With my pictures of pop stars tacked to the wall. I could almost remember….The way it felt to fall asleep in that room on a cool autumn night, the smell of leaves in my nose. The way it felt to wake up in a thunderstorm on a hot summer night. I wished I were home instead of here, falling through the air.

I had many regrets.

I regretted that I’d ever met Kaytee. That was the big one. She was my best friend, my dorm-room partner, and oh, how I loathed her. I regretted also that I’d come to Daytona. I regretted letting Kaytee book Room 712 at the Orange Grove Motor Lodge. And I regretted entering that contest. This morning on the beach. Platforms, speaker towers, banners: “WHO HAS THE BEACH’S BEST BOOTY?”

Kaytee smiled when she saw it. “Let’s sign up.”

“Why would we do something like that? ”

“We’ve got great asses. It’s time the world acknowledged it.”

“Yeah…I don’t think so.”

She handed me the pen. “Print your name. Make it legible.”

A clutch of college boys drank beer and howled. They were shirtless, sun-baked. We stood on a platform and danced. The master of ceremonies hosed us down and told us to shake it like a Polaroid picture. And when it was over and we’d been judged, I found I had Daytona’s fourth-best ass. Kaytee didn’t place at all.

If we hadn’t entered, we wouldn’t have danced. If we hadn’t danced, we wouldn’t have met them. The Goat and John Milton, that is.

It was Kaytee’s fault, of course. It was always Kaytee’s fault. Everything bad that had ever happened to me happened because of Kaytee. She was a needy person. A depraved person. She’d do anything to be liked. Anything at all.

We were in the bathroom, getting ready to go out. Kaytee clamped the flatiron to her bushy red hair. She spent an hour every day straightening that mess.

“So what do you think about those guys? ”

I wrinkled up my nose. “They seem a little old. To be doing what they’re doing.”

“The Goat is hilarious. He totally reminds me of my brother.”

“And that’s a good thing? ”

Kaytee adjusted the silicone pads in her bikini top, then smeared more bronzer on her face. She was all freckles. She burned after seconds in the sun.

“I just meant they’re both, really, whatever. Funny.”

The little bottles of shampoo. The little bottles of leave-in conditioner. The almond-scented soapette. The hair net, the shoe buff. The smell of Kaytee’s flatiron plugged in and warming up.

“I guess I’m not drunk enough yet,” I said.

There was this one time, back home. We got wasted at an Un Cappa Bru party. I passed out on a sofa. When I woke up, next morning, I found out that someone had stolen all my jewellery. My earrings, my necklace, my bracelets—all gone. Even my diamond tongue stud. They’d pried open my mouth and pulled it out. And where was Kaytee then?

She wasn’t content just wrecking her own life. She had to wreck everyone else’s, too.

And when was it, exactly, that things stopped being innocent? When I was a kid it was different. When I was a kid it was ice cream cones and cartoons and picking apples in the autumn. But now…a darkness had opened up inside me. Every particle of my body was screaming for ugly, animal things.

John Milton said, “I’m a professional adolescent.” He said, “Partying, hanging out with beautiful ladies such as yourself—where’s the problem? ”

He’d been coming here ten years straight. That’s what he said. His face was orange and rutted. His hair spiky and blond. He wore a muscle shirt, surf shorts, designer flip-flops. A patch of hair on his chin. He was thirty, thirty-one, at least. He looked artificial.

“We’re filming a movie.”

“What kind of movie? ”

John Milton stroked his chin like a philosopher. “It’s called Spring Break Insanity. Working title. We might come up with something better.”

The ocean was roaring. The sand white and burning. We talked for a while, but there wasn’t much to say.

“And you want us in your movie? ”

“Absolutely.”

“To do what? ”

“Here’s the scenario: two opponents unwinding after the competition. They dance, they drink, they party.”

Kaytee kept touching the Goat. The Goat kept touching her back. He looked just like John Milton, but brown-haired. Same muscle shirt, same muscles. Cracked ketchup in the corner of his mouth.

Things were changing. I could feel them changing, even as I stood there. I’d made some bad decisions, met some bad people. But soon, very soon, I’d leave them all behind. Even here, even now, they were fading to vapour.

Mom and Dad loved me. They also neglected me. I did what I wanted. They paid the Visa. “Have fun in Florida,” Mom said, “but call once a day so I know you’re alive.” She worked in financial services. She had a work phone, a cellphone, a fax.

Everyone worked in financial services nowadays. My mom, my dad, my aunts, my uncles, my parents’ friends. Even the Goat worked in a bank when he wasn’t making art films. If you don’t fall off a balcony, you’ll end up in financial services eventually.

“Hey, Mom.”

“Hey, sweetie. Are you having a good time? ”

“Totally. We entered a contest and met some really cool people, and we’re just having fun and relaxing and forgetting about everything.”

I was on the bed, smoking a doob. John Milton was kneeling on the floor, sucking on my big toe. We hadn’t done anything, John Milton and me. Not yet. But there was a promise hanging between us.

“That’s wonderful, honey. I’m glad you called, but I have to run. Someone’s standing at my door.”

We said goodbye and that was it. In eighty-five minutes I’d fall to the ground and be gone forever.

They say that there’s an unseen spirit-ual dimension to life, that it reveals itself to us if we know how and where to look. But all I saw, as I flailed toward the earth, was physics. All I saw were the laws of nature.

My name was Robin. That was my name. And because my name was Robin, my favourite colour was robin’s egg blue. My bedroom—robin’s egg blue. My wedge pumps, my snowboard, my Volkswagen—robin’s egg blue. It was my colour. I owned it. Even the bikini I wore right now, as I flew through the salty ocean air, was robin’s egg blue. The colour of birth.

The Goat aimed his movie camera at me. His left eye was a slit. His mouth was wide and white and leering. John Milton carried a microphone on a stick. He held it over my head like a threat.

I narrowed my eyes at them. “You want me to do what? ”

“Show us your boobs.”

“What’s my motivation? ”

“Your motivation is you have nice boobs.”

It was all so lame. Transparent and cheap. I had to do it. I had to do it—to mock the whole idea of it. So I pulled up my top and flashed the camera. I did it with irony. I did it with a sneer. Because, after all, boobs are boobs. Every woman has them. And no matter how much they saw of my outside, they’d never see the parts that really counted.

It wasn’t until much later—after I fell off the balcony, before I hit the ground—that I realized none of this irony would come across. There’s no place for subtlety in this world. No place for poetry. Everything was commerce.

What if it was winter? What if it was frigid and dark and I was on my way home after class? What if the bus was lumbering through the unplowed roads, snow was blowing through the funnels of street light, my mittens smelled of wet wool, and my mom had dinner waiting for me on the table? Why couldn’t that be the thing that was real, instead of this?

I didn’t expect the railing to be that slippery. Like someone had smeared it with margarine.

And what if I hadn’t just fallen off a balcony? What if John Milton hadn’t leered at me and said, “Let’s see you dance”? I was a normal girl. I would have had a normal life, eventually. The darkness would have passed. I would have had a husband and a child. A house in Oakridge Estates. But now that was gone. My child had been cancelled. My husband had been cancelled.

John Milton hoisted the microphone on the big silver stick.

“Let’s see you dance.”

“Sure. How’s this? ”

“Beautiful.”

I jumped off the bed and danced onto the balcony. “They say it’s a metaphor.”

“What is? ”

“Dancing.”

“A metaphor for what? ”

“Anger. Sadness. Unrealized dreams.”

“Are you kidding? ”

“Uh-huh. Let’s take things up a notch. Let’s make it dangerous.” I boosted my foot onto the railing.

“Careful there, baby, it’s a long way down.”

“I’m always careful.”

“Maybe you should get down. Maybe this isn’t such a good idea.”

So many decisions to make in a day. So many corners to turn. You can’t always know which way to go. Sometimes left, sometimes right. Sometimes up, sometimes down.

Kaytee and I were lying in the sand, the waves of the Atlantic roaring toward us. The air smelled like salt and seaweed, like fried dough and melted sugar. Cigarette smoke drifted across the beach. It felt like I was turning into liquid, soaking through my towel, down into the earth. I could have stayed there forever.

“Those two boys,” I said.

“Who? ”

“John Milton. The Goat. They’re bad fucking dudes.”

“The Goat’s funny. The Goat’s hot.”

“They feed on weakness.”

Kaytee rolled over and looked at me. Her skin smelled like boiled sausage. “Sweetie,” she said, “who cares? This is Daytona. Nothing here is real. Whatever we do, it’s like it never even happened.”

Across the ocean was Spain. I could feel it out there, behind my eyelids. Its cities were ancient, blood-soaked. To the south was Antarctica, where icebergs slept in electric-blue water. And far, far away was Chernobyl, where all the old buildings had turned into radiant gardens. There was a whole huge world out there, and some of it was real.

The last thing in this world that I’d see was John Milton’s orange and gaping face.

Maybe all I had left now was an interior life. And maybe not even that. Maybe, in a few seconds, as my head cracked like an egg and my brains leaked out over the flagstones, everything would become exterior. My thoughts, my memories, my body. They’d merge with the grass and the trees, and I’d become part of the scenery. I’d float through the air instead of falling, free from all the natural laws. I’d go backwards and forwards in time, reliving my happiest moments. I’d tan without burning, I’d dance without tiring. And I’d never have to work in a bank.

My name was Robin. That was my name. I’d made some bad decisions, met some bad people. You can’t always know which way to go. The ocean was roaring, the sand white and burning. And when the lemon gin hit, it was cold, cold. Everything was commerce. The colour of birth. There was a whole huge world out there, and some of it was real.