It’s four days before Christmas, 2010—the shortest day of the year. For the first time in nearly four centuries, the winter solstice coincides with a lunar eclipse, which, early this morning, caused the sky to turn a reddish hue and made the light dusting of snow covering the ground in downtown Toronto glow. Now evening, much of the city is blanketed with seasonal lights and decorations. The streets are busy, and as a streetcar rolls along College Street, passengers stare through frosted windows at the bustling bars and restaurants lining Little Italy. Not far away, in Kensington Market, flames light up the night as revellers gather to celebrate the neighbourhood’s annual Winter Solstice Festival.

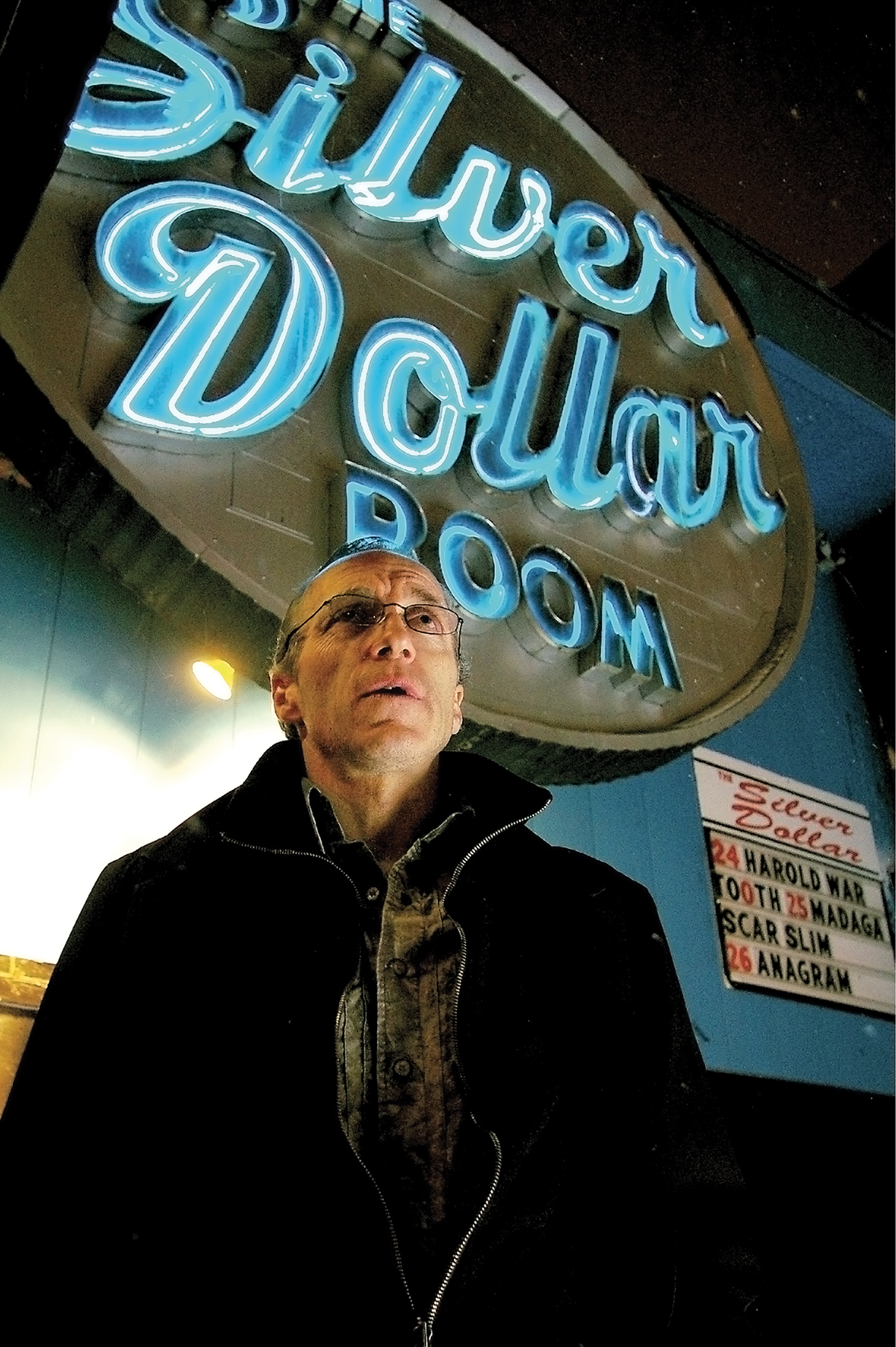

For Dan Burke, perched on a stool at the top of the stairs inside the entryway to the Silver Dollar Room—the music club where typically he works three nights a week—it’s just another Tuesday night. Only tonight, it’s the last place he wants to be. “Right now, right at this moment, I’m tired of this fucking business,” says Burke in a hoarse, raspy voice that can come only after years spent shouting, smoking, and staying up all hours. “Tired of this job. Tired of the hard living. I just want to make some money, enough to get home to Montreal for Christmas,” he says, pulling a wad of twenty-dollar bills from the front pocket of his well-worn beige cords.

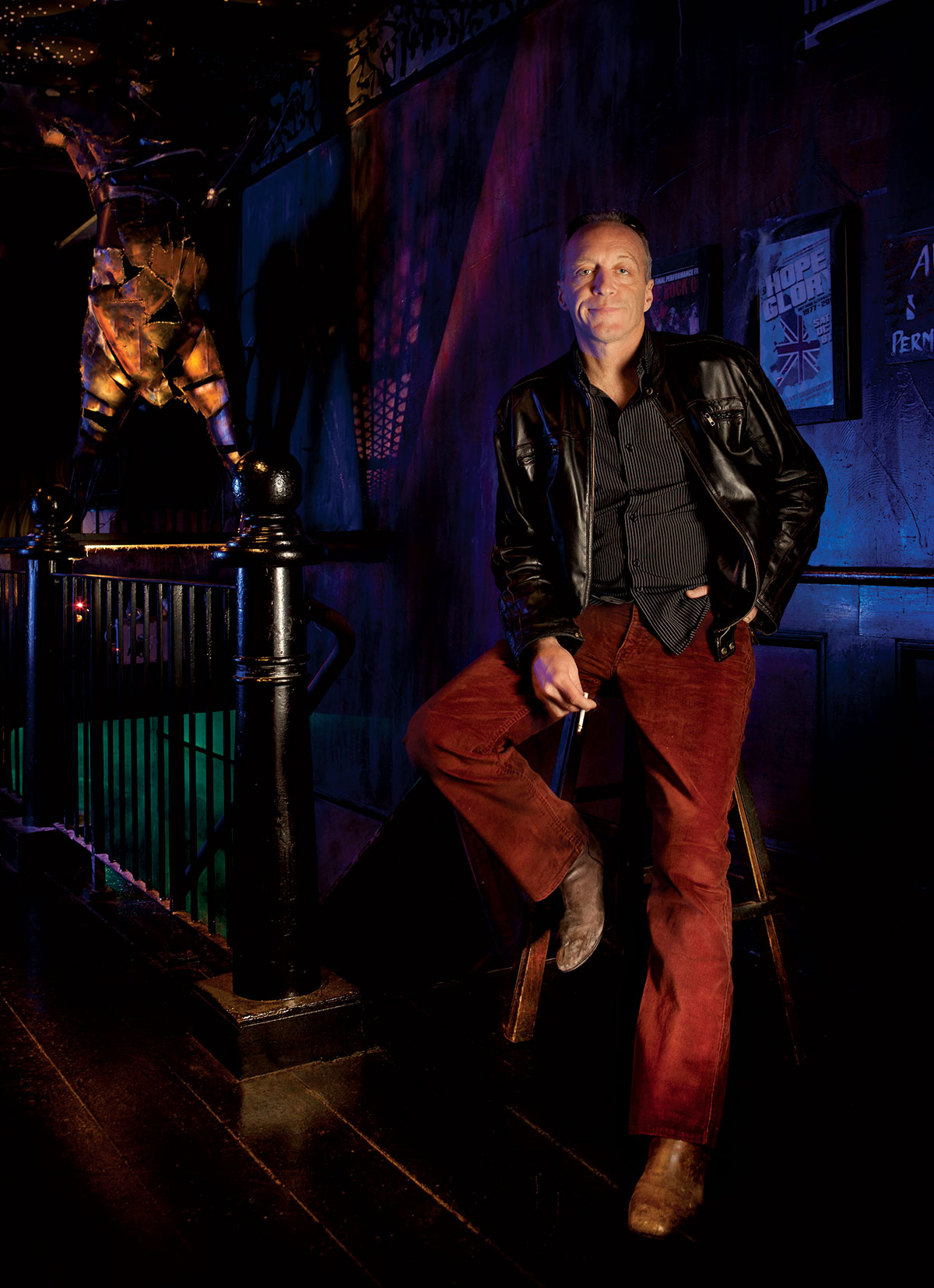

The Silver Dollar’s stairway is harshly lit and lined with autographed photos of former bluesmen who have played the club. Since opening in the nineteen-fifties, the Silver Dollar has had many incarnations: cocktail lounge for the neighbouring Hotel Waverly, heralded blues venue, and, since Burke started booking its acts, in 2003, home to some of the best underground garage rock and punk shows in Toronto. Tall and wiry, Burke, fifty-four, looks fit yet grizzled, like a former boxer who might not last in the ring but could easily outmuscle someone half his age or shuffle an empty beer keg down a flight of stairs. It’s a cool evening, and each time the front door opens, a wintery breeze rushes in. Not that Burke cares. With his winter jacket and a black toque perched above rheumy eyes and a mouth full of broken or missing teeth, Burke looks like he can handle the cold.

A music promoter best known for booking bands such as the White Stripes, Black Lips, Zoobombs, and Nobunny, not to mention the best up-and-coming indie acts, Burke is a workaholic who earns about forty thousand dollars a year, and whose tireless promotion of young groups, coupled with his renegade “fuck-all-y’all” style earned him the title “local hero” in a 2008 issue of Spin magazine. He’s also a former journalist who worked for CBC’s The Fifth Estate and wrote on crime for magazines including Maclean’s and Saturday Night, a hustler, an admitted thief, a recovering crackhead, and a drug abuser and alcoholic. As 2010 comes to a close, Burke is officially homeless and spends most nights in his office above the Velvet Underground bar, on Queen Street West, or at the Oak Leaf men’s bathhouse, where for twelve dollars a day he rents a locker and has space to undergo his workout regime of extremely cold showers coupled with hot steam baths.

Burke has spent the past three-odd years “mostly clean.” The previous week he drank tequila right from the bottle, and in a few weeks, at a Super Bowl party, he’ll attempt to score some cocaine but fail because he no longer has the right connections. “I used to be able to stay up for days at a time, but now it gets to me,” he says. “I used to do every drug, and regularly. E. Powdered cocaine. Crack cocaine. Special K. G. Liquor. I’d be paralyzed for days.”

Burke stands up and looks through the glass window of the door leading into the bar. It’s early, not quite nine, and inside the club a few wait staff stock the bar, checking that the kegs are running smoothly. Two musicians unpack gear beside the black wooden stage adorned with a drum kit, four microphone stands, and myriad black wires and power cords. Burke has booked four bands tonight, including Black Pistol Fire, a raucous drum-and-guitar two-piece originally from Toronto and now based in Austin. “I kind of hope the fourth band doesn’t show up,” he says. (They do.)

The evening’s entertainment is nearly an hour behind schedule, and things aren’t looking good. “The first band, what the fuck are they called? Ghostwalk Greek—they’re supposed to be on already and they’re not even here yet,” says Burke. Neither is anyone else, which, he adds, is kind of a blessing. “If a band’s onstage and playing to no one, I failed at my job.”

Sensing he has a moment, Burke jumps up off the stool and, with the agility of an athlete, descends the staircase two steps at a time. He plucks a half-smoked John Player cigarette from behind his ear, lights up, exhales, and opens the door onto Spadina Avenue. Located on the northern tip of Chinatown and flanked by the University of Toronto and, a few blocks to the west, Little Italy, College and Spadina is a sort of nowhereland—an inner-city island, home to cheap computer stores and a 7-Eleven, which, tonight, is largely populated with patients of the nearby Centre for Addiction and Mental Health.

“It’s painful to have a shit night,” he says. “My reputation is always on the line, every night. If you’re doing a show at the Dollar or the Horseshoe or Lee’s, you’ve got to take it seriously, because it’s only somewhat amateur. Otherwise the place becomes a rehearsal space. There’s no explaining your way out of it—well, there can be, there can be reasons, but the results of your work are plainly obvious. It’s straight numbers.”

Two men and a woman walk by. They see Burke and stop. “What’s going on here tonight? ” asks one, reading the club’s sandwich board. The light from the Silver Dollar’s iconic marquee shines down, casting shadows on the painted red-and-black brick facade, bricks once spray-painted with the words “DAN IS A CRACKHEAD.”

“It’s a rock show. You like rock, don’t you? ” says Burke. Laughs abound. They decide to stay, and walk inside. Burke snuffs his half-finished cigarette and tucks it behind his ear, rips open the door, and jumps up the stairs, passing the threesome midway and perching on his stool. “Five bucks each,” he says, a slight smile forming as he makes change from a twenty. He stamps their hands, opens the door, and peeks inside. A moment later he’s back outside, somewhat reinvigorated.

“I was thinking about writing a story on what it would be like to reinvent yourself. Like someone who doesn’t exist, coming to life. That’s me. I have no I.D., no credit card, no bank account, no pension plan. I don’t go to doctor; I don’t get sick. Although I went to the dentist recently and he said it would be about four grand to fix my teeth. That could be the first part. But how do I begin? I’m a drug addict and an alcoholic with about twelve years left—twelve years of work—and I’m about to reinvent myself.”

In the fall of 1992, Royal Canadian Mounted Police Inspector Claude Savoie received word from above that he’d been transferred from Montreal to take up a new position as assistant director of criminal intelligence at R.C.M.P. headquarters, in Ottawa. To the moustached forty-nine-year-old francophone with twenty-seven years of service under his belt, it seemed like a promotion—a reward for his investigative work and firm handle on, among other things, Montreal’s burgeoning drug trade.

But when news of the transfer reached the staff of the CBC-TV news program The Fifth Estate, the small team of investigative journalists that had been tracking Savoie felt otherwise. Months of research had led them to believe Savoie was a dirty cop, involved with organized crime. At the forefront of the investigation was Dan Burke, a rising thirty-four-year-old journalist who’d spent years infiltrating Montreal’s underworld—as a writer covering crime and as a casual drug user—and for the past year had worked as a researcher on the show.

Initially, Burke gained the inspector’s confidence by telling him he was working on a story about the West End Gang, Montreal’s notorious crime family. But Burke had a card up his sleeve. Through a shared drug connection, he was able to tie a direct line between Savoie and the West End Gang drug kingpin Allan “the Weasel” Ross, then incarcerated in Leavenworth, Kansas.

Savoie had been leaking Ross copies of internal R.C.M.P. documents tracing the progress being made on a case against him, with Ross’s lawyer, Sidney Leithman, playing the middleman. This continued until May of 1991, when Leithman was murdered, apparently for failing to get a Colombian drug lord’s girlfriend off the hook after she was caught smuggling five hundred pounds of cocaine by plane into Fredericton, New Brunswick.

Less than a week before the Fifth Estate exposé on Savoie and Ross was to air, Burke finally confronted the inspector by phone about his relationship with West End Gang leader. Though a shaken-sounding Savoie admitted to having met with Ross, his explanation lacked detail. “He sounded like a man backed into a corner,” says Burke. “Very worried.” Savoie knew he’d been caught—not just by his superiors, but also by Burke himself.

The following Monday, December 21st, the day before The Fifth Estate broadcast, three carloads of Mounties set out to Ottawa from Montreal to meet with the R.C.M.P.’s assistant commissioner, Gilles Favreau, who at the time was in charge of Canadian drug enforcement. It was decided it was time to confront Savoie about his dealings with Ross, which saw Savoie receive more than two hundred thousand dollars in bribes.

Savoie arrived to work shortly after the visiting officers. Having forgotten his security pass, he had to sign in, likely seeing the signatures of his accusers freshly scrawled above his own. He walked up to his office on the third floor. Minutes later, his immediate presence was requested in Favreau’s office. Savoie stood up and closed his office door, wrapped his jacket around his revolver, and shot himself in the head. He was found dead fifteen minutes later.

News of the suicide travelled quickly to The Fifth Estate, shaking the show’s host, Hana Gartner. Burke was unfazed. “People ask me if I felt bad,” he says. “Fuck no. That was the game. He was a dirty cop, and I nabbed him.”

Burke at the Silver Dollar Room, in 2008.

Crime reporting came naturally to Burke, who grew up hanging out on the streets of the largely Irish Notre-Dame-de-Grâce neighbourhood in west end Montreal. Known locally as N.D.G.—or “No Damn Good”—it was the sort of place where kids knew the shopkeepers, where newspapermen and cops, hustlers and gangsters all mingled, drinking beer and Jameson at the same bars—and where Burke’s father, Tim, drank with Mordecai Richler—sharing frustrations that came with working blue-collar jobs.

Montreal was, in the late sixties, the sexiest, most colourful late-hours city in Canada and, arguably, North America. Its downtown jumped and nightlife, the domain of the dominant still-young baby boomer demographic, was full of fleshly delights. Long before the rise of provincial lotteries and licensed video-poker terminals, Montreal was a den of drink, drugs, sex, and gambling, replete with bookies, layoff houses, loan sharks, “and the whole raffish world that gambling once represented,” says Neil Cameron, a Montreal-based writer and historian.

Born in 1957, the eldest of three siblings, Burke stepped into journalism in his late teens as a copyboy for the Montreal Gazette, a job his sports columnist father helped him land. Tough, loyal, and funny, the Burkes were a classic Irish family.

“Dan could be described—like many baby boomers who longed to be part of a world known by their fathers, [a world] dying out in their own time—as a man born too late,” says Cameron, who, in the eighties, worked with Dan and Tim at the short-lived Montreal Daily News. While they were never close, Cameron and Burke were regulars at Grumpy’s Bar, on Bishop Street, and at a long-defunct after-hours club a few blocks west. “Both Tim and Dan struck me as being romantically Irish,” Cameron says, “Pugnacious, hard-drinking, sentimental, and rather fond of the more disreputable elements of Montreal.”

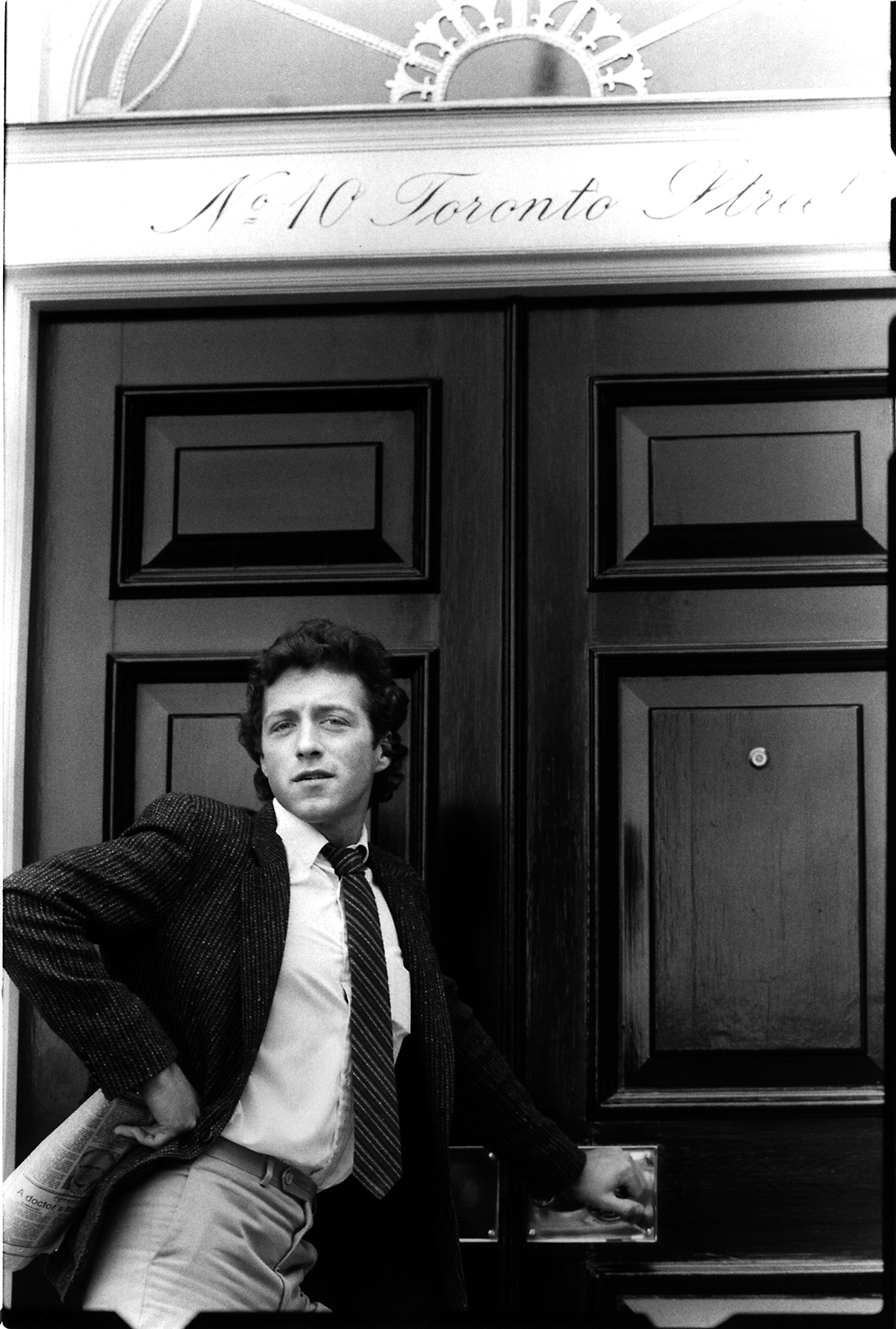

In 1978, after a stint at the Edmonton Sun, Burke enrolled in the journalism program at Ryerson Polytechnical Institute, in Toronto. “Dan was hot,” recalls a past girlfriend who first encountered Burke in a photography class. Well-built and healthy, he’d wear snug-fitting T-shirts with his chest hair curling out the top. “He was very funny, had a slight lisp, and was also a bit of a brawler,” she says. “I seem to remember he had a summer job working on a ship in the Great Lakes, and he’d talk about getting into fights. It was almost like he was from another generation.”

Burke might have had a reputation for brawling, but those who knew him better recognized a talent for writing and the ability to dig deep into a story. Macho yet learned, Burke soon became close friends with a student nearly ten years his senior and equally hard-boiled, John Haslett Cuff. “Danny was like my kid brother,” says Haslett Cuff, a documentary filmmaker who spent twenty years at the Globe and Mail, as a feature writer and TV critic. “We both had a passion for doing colourful stories, the sort of stuff being written by Hunter Thompson and Gay Talese. [Burke] could blend in, he could mix. It was a real talent.”

“If you’d known and seen Burke in the early eighties, he was a star,” says David Hayes, a freelance writer based in Toronto. “I remember meeting for lunch with a publisher at a restaurant in Hazelton Lanes. In walked Burke, looking like a million bucks. He was, back then, a very fit, good-looking guy—in a classic, dangerous, Paul Newman kind of way. And on this day he was wearing an expensive-looking, beautifully tailored suit. I remember thinking, ‘Burke’s really made it.’”

Burke left Ryerson without graduating, taking a job at the Toronto Star before returning to Montreal to freelance. He wrote about the underworld in which he lived, taking on stories no one else would, or could, gain access to, and immersing himself in a lifestyle that would eventually ruin him. In the late eighties, Burke began work on a profile of the Canadian boxer Dave Hilton, Jr., part of the notorious Fighting Hilton family, a once-leading force in Canadian boxing that was eventually toppled by crimes ranging from drunk driving to assault to robberies and, in the case of Dave, Jr., sexually abusing his own children. “He was hanging out with the boxing crowd, snorting coke and gambling, drinking too much,” says a former colleague.

“[Burke] got into some really bad drugs,” says Haslett Cuff. “I remember when he was doing work for Maclean’s, he’d call me up in the day, not about a story he was working on, but because he was high at his desk and thought it was funny.” Near the end of the decade, Haslett Cuff travelled to Montreal at the request of Burke’s family to lead an intervention. “We were all concerned about his drug use. But the intervention failed. I myself had only just quit drinking, and it only got worse for Danny.”

But while Burke was going off the rails, he was also delivering impressive investigative stories, including a 1987 piece for Maclean’s revealing corruption in the office of the Mulroney cabinet minister Roch LaSalle—a piece that provoked the firing of LaSalle’s special assistant and eventually saw LaSalle himself resign.

“Dan was certainly willing to take some risks,” says Cameron, referring to a 1987 Saturday Night feature on the West End Gang and its leader, Frank “Dunie” Ryan. Titled “An Uncommon Criminal,” the story garnered Burke a National Magazine Award nomination for investigative journalism.

“When he didn’t win, he got excessively drunk,” says Hayes, who was with Burke after the awards ceremony. Hayes rode up an escalator with Burke on their way to a party being hosted by Harrowsmith magazine. At the top of the stairs stood the journalist Gare Joyce. Burke and Joyce had had a confrontation at an Irish pub a year earlier when Joyce was in Montreal covering a boxing match. According to Burke, Joyce began taunting him, saying, “You’re not in Montreal any more—you don’t have the mafia to protect you,” and asked Burke to step outside to fight.

“I was with my girlfriend, in a fucking suit,” Burke says. “I wasn’t going outside. So I laughed at him and started imitating pushing weights. I clocked him and he bit me on the forehead.”

Joyce has his own version of events: “After greeting him, I asked him how tough he was without a throng behind him. Then I goaded him into a fight—easy, his head zippers up in the back. There was no hope he could hurt me. He bounced a punch off my forehead and two seconds later I had him pinned to the floor. I bit his forehead as I choked him. I wanted to hear him scream, to make sure he was still alive.”

As security arrived to put a stop to the fight, Hayes continued on to the Harrowsmith party. Burke arrived at the door soon after. “They took one look at this drunk, mad guy with blood rolling down his forehead, and some of them literally hid behind the curtains,” says Hayes.

Today, Burke’s disdain for Joyce remains at a boiling point. “[Joyce is] too stupid to write about anything but sports,” he says. “I’d fight him today. I’m a hundred and eighty pounds now, you know.”

“[Burke’s] a marginal writer befitting his not-even-marginal character,” says Joyce. “All water finds its level, and Dan Burke is a fetid puddle in a cranny of a sewer. This is an obit you’re writing, I hope? ”

Burke launched a successful campaign to restore the El Mocambo’s historic palm tree sign in 1999.

After helping shake such an established institution as the R.C.M.P. to its core, Burke was on a roll. Things were working out at The Fifth Estate, where his quick wit, easygoing manner, and renowned research abilities let him get close to subjects and sources few others could tackle. “Dan’s journalism was based in the notion that, if you travelled with a down-and-out side, that’s where you found the essence of life, the essence of a story,” says Linden MacIntyre, a long-time reporter for The Fifth Estate.

With a shared interest in Irish politics and history, plus the fact that MacIntyre was fifteen years older than Burke, thereby representing the generation of sleeves-rolled-up reporter Burke so admired, the two men hit it off, working together on several difficult stories, including one about a New Brunswick man accusing his uncle of killing his younger brother. “Dan caught wind of this story, tracked down both men, and then cooked up the idea to bring them together in a motel room,” says MacIntyre. After much buttering by Burke—chain-smoking the uncle’s cigarettes the entire time—the uncle, who wanted nothing more than to confront his accuser and talk things out, was led in a van to the motel, where his nephew and a camera crew were waiting. “They started screaming at one another, ‘Fuck you, you killed my goddamn brother,’ and so forth,” says MacIntyre. “It was amazing television.”

But by 1993, Burke started to slip. His drug use was escalating, eclipsing his investigative persona. “The first sign for me was when a story we’d been working on was sabotaged, accidentally, by Dan,” says MacIntyre, referring to a months-long investigation that had Burke regularly conversing with a source’s lawyer. “We were this close to getting what we needed, and then Burke started acting weird and the lawyer backed away. I was really pissed off.”

The story was a bust, and though he’d been recently promoted to associate producer, Burke’s antics were now well known within the CBC. Colleagues, led by Victor Malarek, a fellow Montrealer now with CTV’s W5, struggled to get him into rehab. “Victor went out of his way to help Dan, took him to detox, lent him money,” says MacIntyre. Word began to spread around the CBC that Burke was in freefall. “He’d say things like, ‘I want to live the life rather than talk about it,” says MacIntyre. “For a long time, I thought he was just researching something, working on a novel, but he was just out of control, trying to give it a romantic gloss.”

In December, 1994, in a mid-day drug-induced fog, Burke stood up from behind his desk and walked out of his CBC office, never to return to work. Not long after, Burke was summoned to the office of Bob Culbert, CBC-TV’s executive director of news and current affairs, for a meeting. Culbert, a former newspaper reporter who spoke with an Irish accent, had a soft spot for Burke. “Bobby called Dan in and said he’d help him; that the CBC would do whatever it takes to get him back on track,” says MacIntyre. “Burke listened, and then said he didn’t want to be back on his feet, and asked Bobby for a twenty dollar loan.”

Burke’s new occupation: crackhead.

From the end of 1994 through early 1997, Burke was, in his own words, “living rough.” Largely homeless, at least by most definitions, and working odd, temporary jobs, the once-respected journalist was now a petty thief—nothing more than a Chinatown rubby.

“Dan became a character in his own life,” says MacIntyre. “I think he knew this, and it brought him comfort. He never looked down on people that were down and out. And so now he could look at them and say, ‘I’m one of those people, too. So be it.’”

Burke’s friendships snapped apart, and those who tried to help him were rebuffed, including Haslett Cuff, who offered Burke a job researching a documentary. “We hired him because of his research skills, but he just got high and fucked up,” says Haslett Cuff. “I was cruising crack houses in Regent Park, looking for Danny and the rental car we’d given him.”

Burke’s appearance had also deteriorated greatly. No longer the lady-killer in tailored suits, he took on the look of someone who spent his nights outside, his days crashed on a shit-stained sofa. “I’d run into him occasionally,” says Haslett Cuff, “and each time he’d look a little worse—fewer teeth, hoarser voice, like he’d just stepped out of the Scott Mission.”

Among his many odd jobs, Burke was selling wholesale flowers with some businessmen in Chinatown. While looking for storage space to rent, he came across a third-floor pool hall just south of Dundas Street, on Spadina. The building’s owners, unhappy with the hoodlums and loiterers shooting stick and dealing drugs, were looking to transform the space into a music venue. “They asked me if I knew anything about running a club, and I said yes,” says Burke. It was a lie, but Burke felt that with his research skills and general stamina for nightlife, he could do it. “That’s how I got into this business, wayward and lost.”

Burke knew he would have to get clean to make his new venture a success. He started attending Alcoholics Anonymous meetings and stopped smoking crack. Scouring the city’s weeklies, he discovered who the players were in the local music business: the other bookers, the rising bands, the different crowds. Burke booked the types of acts he related to most: down-and-dirty rock, punk, glam, and garage. “I didn’t know anyone in the music business,” says Burke. “I’d read through the weeklies, get a feel for the story, and then try to set something up.” Working seven days a week, Burke set his sights high, hoping to create a music venue that would become synonymous with an era, a defining point of the city—Toronto’s CBGB.

Burke, as a Ryerson student, knocking on the door of the media baron Conrad Black.

On the Canada Day weekend, 1997, Club Shanghai opened its doors. The timing, Burke admits, was a rookie mistake. Being a long weekend, no one was in town. One night in and Burke was back on the pipe. But then, slowly, Club Shanghai started to gain notice as a place to see young, exciting bands such as the White Stripes, Sloan, the Brian Jonestown Massacre and the Deadly Snakes. It also became the new home of Davey Love’s popular dance party, Blow Up.

But as Club Shanghai gained in popularity, Burke’s relations with the building’s owners began to sour. By mid-1998, Burke quit. He received a buyout of about twenty-three hundred dollars, which he spent in four days. Meanwhile, Love had moved Blow Up just up the street, to the El Mocambo, home to legendary Toronto shows by international artists including the Police, the Ramones, Elvis Costello, Jimi Hendrix, and the Rolling Stones—who performed a surprise set in 1977 to an over-capacity crowd, including a recently separated Margaret Trudeau. But by the late nineties, the El Mo was tired and decaying. Even its iconic palm tree marquee, erected in the nineteen-forties, was barely visible, its lights knocked out long ago.

Still, it was something, and when Love told Burke that the El Mo was in need of a booker for its upstairs room, he quickly landed the job. Though the venue still had an international reputation, by 1998 it had become shunned by Toronto’s indie bands, who perceived it as an industry club where record companies showcased packaged artists looking for a deal. On the verge of closing, it was nearly as bankrupt as Burke himself.

“I wanted to make the club significant again,” says Burke, who quickly began to breathe life into the space, bringing in bands he’d read about, such as the Detroit Cobras and Tokyo’s Zoobombs. “You’d see him on a payphone, booking some band from Memphis that nobody in Toronto had even heard of,” says Clint Rogerson, who plays in several Toronto bands, including Action Makes. “The Black Lips, Brian Jonestown Massacre—Dan was the first to make that shit happen.”

Like a New Hollywood auteur, Burke became the in-house attraction. With his freeform dance moves, pugilist pose, and seemingly endless stamina, he was something to behold. “There’s been a lot of shows where nobody’s having a better time than Dan,” says Rogerson, noting that sometimes Burke had too good a time. “He’d get a couple drink tickets that were supposed to be for the bands, and he’d be at the bar: Scotch. Scotch. Scotch. And then suddenly there’d be an altercation or misunderstanding that would escalate into a brouhaha,” including one fight that put Burke in a coma for two days.

Burke finally was making decent cash again, enough to contribute some funds toward getting the El Mo’s marquee back into working order. He also had a girlfriend, his first serious relationship in years. Soon working both floors of the club, Burke’s reputation as one of the city’s best bookers was waxing. Finally, there was stability, fame, and funds all at once.

Then, a slap to the face: the building housing the El Mocambo was sold and the club was shutting. Burke was in shock. He had forty-five days to get out before the legendary venue turned into a dance studio.

On his final night, November 4, 2001, Burke pulled out all the stops for a show that culminated in him flicking his sunglasses at the new owner and being arrested for alleged assault. It was to be another miserable winter, and by the following May, the majority of his eighteen thousand dollar life savings had gone down the pipe.

It was the beginning of a narcotic blur that lasted for nearly seven years, and included several failed-yet-creative attempts—including a somewhat fruitful residency at the short-lived Tequila Lounge near the Annex neighbourhood—to reclaim his place in the city’s growing music scene. Still determined to make it as a booker, Burke supplemented his meagre wages by shooting pool and spent weekends dancing till dawn at the somewhat disreputable Comfort Zone, an after-hours club situated next door to the Silver Dollar, where he narrowly avoided a mass police raid in March, 2008, that saw dozens of arrests. “If I’d been there, I would have been nailed,” says Burke. “That’s when I started to change. I woke up and thought, ‘Fuck. Holy Jesus, this is heavy.’”

“Just tell him to just fucking drive down. Tell him he can park out back.” Burke takes a drag from a cigarette, cranking his neck to hold the phone so he can look through the pile of papers strewn across his desk. He’s sipping a large coffee and somehow standing and sitting at the same time, unable to find the right position. A stream of smoke sits in the air, illuminated by the overhead lights in the windowless basement office of the Silver Dollar.

“It’s Friday, March 11, 2011, the third day of Canadian Music Week. Over the course of four nights, Burke will present more than forty-five bands at three separate venues: the Comfort Zone, the Silver Dollar, and the Velvet Underground.

“I’ve got big plans this year,” he says, locking the door and walking downstairs to the Comfort Zone. A small crowd has gathered in the club and, even though it’s early, Burke is annoyed by the scene. “Look at the fucking stage—there’s a door open and it’s letting in light. It looks like shit.” He grabs some electrical tape and, between songs, tapes the door closed. “It’s the small details that matter most. The sound. How things look. It annoys me when you can tell somebody hasn’t put in the effort to make things perfect.”

Upstairs, at the Silver Dollar, things are looking a bit better, as the country singer Katie Moore plays to about seventy-five people. “She’s great—from Montreal, you know,” says Burke, clearly content with the early crowd and that he was able to score Moore, whom, he believes, is set to blow up big. Burke is in a great mood tonight, nervous yet energized, frightened of the future but ready to adapt. No longer escaping into drugs every day, he is clearly trying to make his mark as a legendary booker.

“Dan’s returned to ace form these past few months,” says Rogerson. “He’s collaborating with other bookers, putting on some of the best shows in the city.” It’s a new era for Burke, who in the past refused to take part in Toronto’s major music festivals, including the lucrative Canadian Music Week and North by Northeast, the latter of which Burke once ran a counter-festival to. “[The NXNE president Michael] Hollett recognized I was making a valid point with the adversarial shows—point being, the festival could be a lot better than it was,” says Burke. In 2006, Burke began working with Hollett on NXNE, which he now deems “a brilliant festival.”

Collaboration isn’t just helpful, it’s necessary in a city like Toronto, where a single player dominates bar-level booking: Collective Concerts. The talent buyer, led by the promoter Craig Laskey and run out of the Horseshoe Tavern, has created a virtual monopoly on touring bands, as evident by the double-page spread of upcoming shows that runs each week in Now. “They get all the shows,” says Burke. Still, as successful as Laskey is, he is largely invisible—a behind-the-scenes roadie to Burke’s onstage star-of-the-show persona. “I’ve never seen him this rejuvenated, this jacked up, and basically clean,” says Rogerson.

Burke has also been reuniting with some old friends. “He’s still alive, so he must be doing something right,” says Haslett Cuff, who met with Burke recently to shoot pool. “I don’t know the nature of his survival, but he seems better than he’s been in a long time.”

Within the next six months, Burke will have landed an apartment of his own and have more in his pockets than a wad of cash, including a cellphone, a birth certificate and an Ontario health card. Before the year is out, he’ll also have a full set of teeth. “I got a full set of upper teeth now,” he wrote in an E-mail at the end of a gruelling Canadian Music Week. “After going to sleep at 5am on Saturday morning at the Silver Dollar… I got up at 9am and went to the dentist. He did three more extractions, including the remainders of my top left front tooth, put stitches and temporary plate in—and then I went and did my three final shows of the festival.

“What a fucking weekend.”