The night of my sister’s wedding, I burn my bridesmaid dress in the scrubby alley beside my apartment building. The seafoam-coloured silk melts slowly, and gives off a smell like burned hair. In its thin glow, I make a decision: I will buy a wig and become a Joni Mitchell impersonator.

I quit my telemarketing job and withdraw my savings. I ask a friend to move into my apartment for a while, and he accepts. Having never really been anywhere, I walk to a public library and use an atlas and the internet to draw up a list of towns I think will be small enough to book an act like mine, then add the numbers for local hotels and bars. I make a series of calls. Using my trained telephone manner, I have no trouble setting up a string of gigs.

I take the subway downtown and find the wig I need at a shop that also sells beaded curtains, bongs, and old issues of Heavy Metal. At home, I bend over, pull on the wig, and stand up quickly, throwing the new hair back over my shoulders. It is long and blond. I look at myself in my small, medicine-cabinet mirror, the short tube of light buzzing above me. It makes the wig almost white at the crown, and my skin and eyes nearly grey. I don’t stand there long.

I buy sheet music for all the Joni Mitchell songs I can find, and spend a long time neatly writing out the lyrics. My phone rings often but I ignore it. I write a note for my friend. He can relay the news to my family. I stuff my backpack with jeans and loose shirts, snap my guitar case shut, take a cab to the Greyhound station, and buy a bottle of water, a cling-wrapped egg-salad sandwich, and an open-ended cross-country ticket headed west.

On the bus, I claim a window seat. The sight of the disappearing city is dreary in the late-fall grey, but it isn’t long before deep, gold-brown farmers’ fields, then rusty rock cuts and pine trees, take its place along the highway. The bus stops often to drop off packages and give the smokers a chance to rush down the metal steps and get some air. The person beside me keeps changing: an older Native woman who knits and nods, a university student wearing earphones who stares at my wig and also at my boobs, then a mother who ignores her five-year-old as he runs up and down the aisle.

“I’m a musician,” I tell each of them. (The student has to pull out an earphone to hear me.)

“What kind of music? ”

“Folk.”

“Ah.”

The Star Motel, in Gravenhurst, is my first venue. I’ve been offered free dinner and a room for the weekend, but no pay. I meet the manager at six. In person, I am less confident than over the phone, and he eyes me over his bifocals with open disappointment—probably thinking I am too short and too dumpy to be Joni—says I’m lucky a new-country trio bailed on him, but I can tell by looking around the low-ceilinged bar that, one way or the other, the place’s reputation is probably sealed. We go over the set-up and he recedes into a dim backroom. I order chicken fingers and fries, finish my plate, then walk across the cigarette-burned carpet leading to my room. There, I make a single call and get the answering machine. “Hi, Mom. It’s me. I’m sorry I missed the present-opening…and the goodbye dinner…and all the rest of it, but I had to get going. Don’t worry. I’ve finally got something worked out for myself.”

I am relieved to find there are only six people in the audience when I step up onto the plywood stage to begin my set. Two of them are older men, who sit across from each other and ignore me. They lean together, laugh in phlegmy spurts, and slap one another on the shoulder over their pitcher. One woman sits alone, cigarette smoke winding up from the ashtray near her elbow. The others look like summer students who’ve been drinking since noon. The bartender paces in the long space behind the bar with a dish towel over one shoulder, clinking glasses as she goes. I stand a moment, waiting for my courage. It arrives with the manager, who reappears from the backroom to lean on the bar, looking a little like a mobster.

The first song I play as Joni is “Blue.” Then “Case of You.” Then the song I sang for my sister at her wedding. I recognize that they had a point back then: my voice is wrong for Joni Mitchell covers. But the wig is right, and so are my jeans and loose cotton top. I smile as a few more people trickle in, and nearly all of them clap quietly as I finish my first set. I hadn’t expected anything more—and probably a lot less.

I have a better show in Sudbury, and am paid for it. At the Canadian, in Sault Ste. Marie, I get too drunk on free draught and screw up the words to “Little Green.” I apologize into the silver ball of the mic and the sparse audience gives me a staggered consolation clap before returning to their Wednesday night drinks. At the Whalen, in Thunder Bay, a drunk man shouts out, “Show us your tits!” but I don’t. In Steinbach, Manitoba, the tiny Green Tree Café is full to capacity with people I later realize are Mennonites. They are my first sober crowd, and stand and clap as I finish, even though I’m sure I have been off-key. A short woman in a long skirt approaches the corner that’s been cleared for my footstool and mic to tell me I am beautiful. Mennonites really are generous—no one has ever told me that before.

That night, in my motel room, I dream of a wedding. It is a lot like my sister’s wedding, but there are important differences. My sister, when she lifts her veil, is bald. Everyone is horrified. They turn together to find me, the maid of honour, wearing a flaming seafoam silk dress and a blond wig. I run, and the entire wedding party chases. I stumble and fall. I look up from the ground, and find I have fallen at the feet of Joni Mitchell. Joni’s eyes shine like emeralds. With the power of her mind, Joni lifts me up. Then we are flying together over rolling hills made entirely of sheet music, passing a group of waving Mennonites. The dream wakes me. I am bathed in sweat. I take an extra-long shower, and give my wig a thorough wash and blow-dry before checking out to reboard the Greyhound.

I sing in Carman. I sing in Brandon. And I sing in Moosomin. Between these gigs, and the free chicken fingers, I save enough money to afford a day off. I book myself into a bed and breakfast in Wolseley, Saskatchewan. The bus drops me off in the early evening. The sun is already down. I follow directions and walk along a dark road, then over the railroad until I find it—a converted brick farmhouse with little white lights in the bushes outside. Classy. The girl at the desk asks about my guitar. I tell her I’m a musician, and she smiles as though this explains a lot.

In my room, I am disappointed to find there is no TV. I walk down to the tiny basement pub. As I enter, everyone turns to stare, give me cool smiles, then go back to talking and watching Robot Wars on an overhead TV. The girl from the desk comes downstairs and takes my order. I drink a Molson Ex and watch the robots. I order another, then another. I try to piece together a kind of mental scrapbook of my performances to date.

A young farmer comes in and sits alone with a beer. He looks over at me several times.

“I’m a musician,” I say, not knowing how else to acknowledge his attention.

“Really.” He says nothing more, but looks satisfied.

The local news comes on. During a report about a recent drop in wheat prices, the farmer turns in his chair and says, “I play synthesizer. Got the whole thing set up with the computer now. I can just make all this music. Great way to waste time. Specially now, after harvest.”

“Yeah,” I say.

“Is that a wig? ” he asks, tentatively, then glances over at the other people in the bar, who are staring at us.

“No,” I lie, and immediately regret it. “Yes.”

“O.K.”

“It’s new.”

“No problem.”

We are silent for a moment.

“Ever recorded? ” he asks.

“No, no. I just do covers. Gigs.”

“You here long? ”

“No, just taking tomorrow off, then I gotta get to the Alberta border.”

“Well, you can come and see my set-up if you want. Farm’s just up past the graveyard.” He gets up from his table and stands over me. He makes me a map on the thin damp coaster that the waitress placed under my beer glass.

“Thanks,” I say.

“Come out,” he says, and walks to the bar to pay. The regulars are looking at him, then at me, and I wonder what they make of it. I don’t wonder long. I get up a few minutes after he leaves and go outside with my map. I want to walk and think.

I follow the directions, but get confused. Fifteen minutes later, I am still on the residential streets of the town, and not anywhere close to a graveyard. I double back and realize I have to use the bathroom quite badly. It’s the beer. I notice lights on, and lots of cars parked around a grade school. I try the side door and find it’s open. I walk down the green hall, lined with low coat racks and classroom doors, looking for a bathroom.

Behind me, someone pops a head out from a door. “Hey! Janet! Hey!”

I turn and see a woman in heavy makeup, waving. “Come on. You’re late. It’s almost time.”

“What? ” I yell back.

Another woman comes out from the door dressed as a fisherman with a fake moustache, suspenders, and wading boots. The two are gesturing for me to come over. I really need to go to the bathroom, but I turn and walk toward them.

“Who are you?” says the first woman, her forehead scrunched in annoyance, as I approach the door.

“I’m just here for the bathroom.”

“Where’s Janet? ” says the fisherman.

“I don’t know who that is,” I say.

“Why do you have her wig then? ” they say, pretty much at the same time.

I hesitate. I am not sure why I have Janet’s wig. I put a hand up to touch the top of my head, a bit protectively.

The first one looks upset. “Look, Janet’s really late. You’re not from town, obviously, but if you know the part, then all she had to do was call and tell us she was sending you. I mean, the mermaid scene is coming and the whole group’s getting nervous. We’ve been calling her number for a half-hour. Jesus.”

“O.K.,” says the fisherman. “Let’s calm down here. Do you know your part? ”

“Yes,” I say, not sure how else to answer. I do know my part.

“Good. Let’s get a tail on you then.”

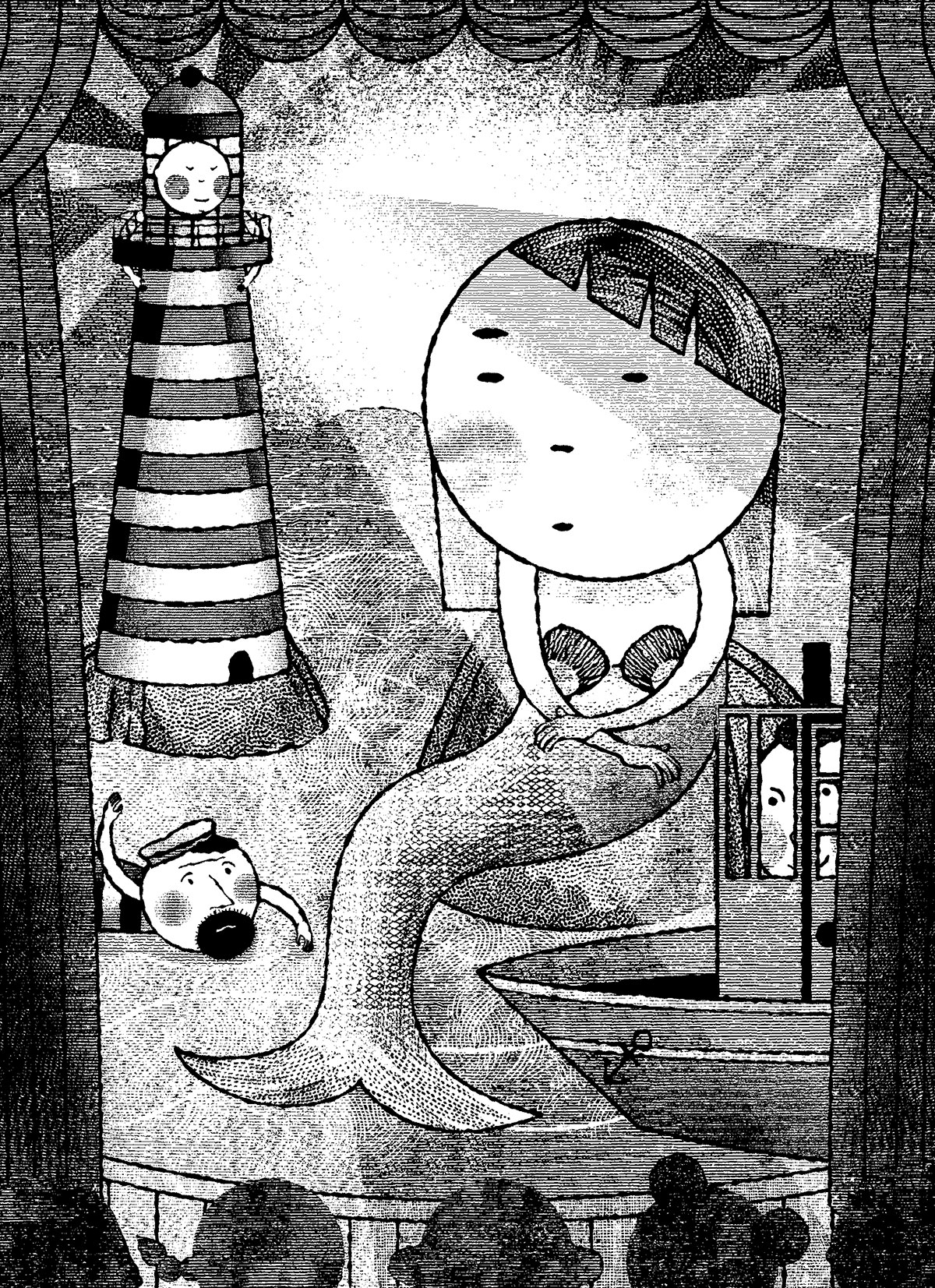

They rush me in through the door, which opens onto a corridor. I hear singing, then a burst of applause, and realize we are backstage. I am not sure what to do, but I can’t turn back. I really can’t. We get to an area where other adults stand, dressed in costumes—more fishermen, a whale, some sailors, and a man dressed as a lighthouse. Everyone turns and sees me. I see questions come into their eyes.

“No time for explanations,” says the first woman from the hall. “Get the tail. She’ll be the mermaid.”

I have on the costume. My legs are not free to move much. A large swath of the iridescent green material swings out to the left of my ankles into the tail. On top, the costume is like a brassiere, with big blue seashells sewn into a skin-coloured bodysuit. Janet must be smaller than me, because it’s too tight across the back. I stand in the wings and wonder what I am doing. No one stands still long enough for me to ask. I can see the actors on stage. I can see a slice of audience through the mist of the stage lights. I have been on stages before.

Then, it’s my turn. I know because the woman fisherman comes up and gives me a push. I am out on stage, walking in tiny steps over to a big fake rock that must be meant for me.

I sit. A fisherman, this one played by a man, stands across the stage, beside his boat.

“The gods are toying with me!” he says excitedly, swinging an arm with dramatic flair up and in my general direction. “How else to explain that my eyes, my hungering dry eyes, this moment behold the greatest beauty there is? ”

“Don’t be fooled,” says the boat, who is really a man in a brown triangle of boat-shaped foam and tights. “She is but a mirage! You have been looking so long, you couldn’t tell a mermaid from a Minotaur—anything real from the products of your starved stomach and insolent whim.”

Some people in the audience chuckle.

“No!” says the fisherman, walking toward me in slow steps. The boat keeps pace with him. “You’re wrong. And why am I talking to a boat anyway? ” More chuckles.

“It is true, I am lonely. I have been at sea for such a long time that my eyes could play fools to any whim, but they do not do so now. Oh no! This…this vision before me is real. Real as my heart, anyway. Real as the love that grows in me like the storm that swept me to this terrible place so many moons ago. How could such beauty fool? Why, just listen! Listen to her sing!”

The actor pretends to leap from the boat.

“Doooon’t!” cries the boat, his mouth, which is nearly lost in the brown face makeup, stretching into a wide “o.”

The fisherman pretends to swim over to the rock where I am sitting. He is looking at me hard, as though it is my turn.

“I say—just listen to her sing!” he says again, and everyone is silent.

Someone in the back of the gym coughs. Offstage, the woman from the hall gestures to me wildly. “Sing!” she mouths.

And so I do. I sing the song I know best, the song I sang at my sister’s wedding. I try to imagine that I am the mermaid. That I am Joni. That I am exactly as I’ve always wanted to be: far away, and very close and happy. That I am beautiful and free, and most of all, real.

“I’ve looked at life from both sides now / From up and down, and still somehow / It’s life’s illusions I recall / I really don’t know life at all.”

When I am finished, the actors are silent. The fisherman is still on the ground, staring up at me, confused. The fisherman played by a woman, offstage, looks angry. A woman in a blond wig identical to mine stands beside her with wide eyes—Janet.

But the audience, the audience is clapping. They are up on their feet, and they clap for me. I stand, careful not to fall over my tail. I don’t yet think of my wig and how silly it is. I don’t think of the tightness of my costume, or the way I am bulging in the middle of it and around the top, or my sister, or my mother’s answering machine, or my next gig, or how I will cancel it. I think of the warm lights that line the stage, and of the farmer and the map that’s in my jeans, and how it will be easier to find him in the morning.

I take a long, low bow and exit, stage left.