The Atlantic National Exhibition midway in 1978, including the infamous Zipper, to the left.

Forest Hills is a suburb located on the east side of Saint John, New Brunswick, in an area known as the parish of Simonds before it was amalgamated with the city, in 1967. Development of the neighbourhood began in the nineteen-fifties. It was built, as its name suggests, on a hilly range, heavily forested and dotted with fields. My parents were among the first residents of Forest Hills when, in 1958, they purchased a small, three-bedroom bungalow on Braemar Drive, a short street of twenty-five houses that runs straight along the hill’s base, before curving up and to the right in its final leg. All of the neighbourhood’s amenities are located adjacent to Braemar, including a convenience store, a Bank of Nova Scotia, and a red-brick strip mall that, during my youth, in the nineteen-seventies and eighties, housed a Kentucky Fried Chicken, a public library, a pool hall, a hair salon, and a Chinese food restaurant. For years, several undeveloped fields opposite this strip marked the entryway to Forest Hills. Parkway Mall opened on one of them in the mid-seventies. McAllister Place, another shopping centre, followed soon after. One portion of field that remained undeveloped ran flush against Braemar Drive’s backyards, acting as a buffer between the neighbourhood and about sixty-five acres of land known as Exhibition Park. At the north end of these grounds sat several horse stables, a large wooden grandstand, and a racetrack. Toward the south was the Simonds Centennial Arena ice rink, and an equal-sized exhibition building, where car and boat shows sometimes were held. A ball field, overseen by the Simonds Lions Club, was located to the east, and easily accessed by neighbourhood children though a series of well-worn paths that led from behind many of the homes on my street. In the centre of the exhibition grounds, a paved area of approximately seven acres usually sat empty, with the exception of one week each August, when the event that gave the area its name took place.

From the year I was born, until the summer I turned seventeen, I spent the week before Labour Day at the Atlantic National Exhibition, an end-of-summer rite for the residents of Saint John, especially those who, like me, could see and hear the attractions from their house. The A.N.E. was smaller than both Toronto’s Canadian National Exhibition and Vancouver’s Pacific National Exhibition, but was comparable considering Saint John’s population, which peaked in the nineteen-seventies, at just less than ninety thousand. The A.N.E., like all exhibitions with roots dating back to the nineteenth century, slowly shed its industrial origins and evolved into a spectacle that entertained more than it educated. There were small rides to scare children, bigger rides to scare adults, balloons to burst with darts, and clown heads to topple with baseballs. Burlesque dancers performed in an adults-only tent, and a freak show drew crowds well into the nineteen-eighties. Trailers scattered throughout the midway offered tattoos and tarot card readings. Rooty, A&W’s Canadian-born Great Root Bear, roamed the grounds at least once, while his compatriot Ronald McDonald visited on a regular basis, often staying long enough to put on a show for children. Onstage entertainment ranged from popular headliners like Tommy Hunter, Ronnie Prophet, and Jeannie C. Riley to B-list travelling performers to local talent. Single girls between the ages of eighteen and twenty-five possessing “good character, poise, intelligence and beauty” competed for the crown of Miss A.N.E. Small permanent wooden buildings around the grounds’ perimeter showcased work by amateur painters; homemade quilts, pies, and preserves; and various species of fish and game. The food building, like the city itself, was populated mainly by mom-and-pop vendors, supplemented with an occasional corporate retailer, such as Dairy Queen. Dozens of exhibitors and vendors set up in the main building, across from the rink; some of them were transient, but others, like CHSJ radio and Fundy Cable television, were annual anchors.

When I was very young, I spent a lot of my exhibition time behind the booth hosted by the Canadian Red Cross Society, where my father worked as the provincial director of water safety. Every year, he spent the week educating passersby on proper paddling techniques, extolling the importance of C.P.R., and—at least once with my assistance—demonstrating life jacket safety on local television. My mother and I attended the daytime entertainment, held on a custom-built stage in the Simonds arena. Many of the afternoon acts were aimed at children. (I still own a 45 r.p.m. keepsake of Billy Earl and Henrietta the Singing Chicken, a touring ventriloquist act.) We also made frequent visits to the bingo tent, where dried corn kernels were used as card markers. I won more often than my mother did, which caused some tension and guilt when inevitably I chose a frivolous prize instead of one of the useful household items she would have preferred we take home.

I didn’t like candy apples, but enjoyed a stick of pink cotton candy, which was available from a number of vendors, including one much maligned stand that looped a custom cover of “The Candy Man” non-stop for every hour the exhibition operated, and that could be heard from my house. I rode the mini-train, coasted on a burlap sack down the giant slide, crashed bumper cars, and got lost in the glass house. After some early stomach trouble on the Tilt-A-Whirl, I moved up to the Teacups, the Scrambler, and the Gravitron—a deceptively named ride that owed its popularity more to centrifugal force than gravity.

When I got older, I attended the exhibition with friends. My neighbour Andrew Gordon lived in one of the homes with a path leading directly from his yard to the fairgrounds across the swampy field. I received a free admission pass to the Ex for years after my father retired, but sometimes Andrew and I still tried to sneak in by scaling the fence at the back of the fair. I moved up to larger rides, like the Ferris wheel, the Polar Express, the Spider, and the Pirate. Andrew insists to this day that someone fell to their death from the Zipper when a cage door opened mid-ride, but I’ve never been able to find any evidence of this, and I’ve heard similar Zipper myths from people who grew up in other parts of the country.

One year, I became obsessed with trying to win Cover the Spot, a midway game in which the mark is given five metal disks to drop onto a red painted circle. To win, the disks have to cover the spot completely, and they cannot be moved once dropped. I spent what must have been close to a full summer’s allowance on Cover the Spot that August, but despite the carny’s deceptively easy-looking demonstration and the theatrical encouragement he gave me every day, I went home on closing night frustrated, poor, and minus a prize I didn’t even really want in the first place.

My final visit to the A.N.E. before I left home was in 1990, the year the exhibition celebrated its hundredth anniversary. Ride tickets cost sixty cents each, but could be bought in advance from Sobeys grocery stores for half price. Entertainment was provided by Kelly Garver, a pop and country fiddle player who had been Miss Michigan 1986, and a juggler who performed at the White House for the first President Bush. The fair ran for two extra days to mark the occasion, and attendance reached a ten-year high.

The concept of national exhibitions to showcase technological innovations and advancements originated in France, in the late eighteenth century. In Saint John, exhibitions, fairs, and circuses have been a part of the local culture since at least 1818. The names of these events varied, but often included a grand designation like “Provincial,” “Canadian,” “International,” or “Dominion.” The city’s first major exhibition took place in August of 1842. It was organized by the directors of the Mechanics’ Institute, and held in the group’s hall, on Carleton Street, with a stated purpose to encourage commerce and education in the areas of art, science, and nature. In 1851—the same year of Prince Albert’s Great Exhibition, in London, and two years before New York’s first World’s Fair—Saint John held Canada’s first industrial exhibition. Commercial transportation methods were still limited, so most of the exhibits displayed locally made wares. This sounds narrowly focused, but a considerable number of goods were made within the city limits. Saint John soon would be Canada’s fourth largest city, after Montreal, Toronto, and Quebec—the 1861 census reported a population of 27,000, made up in large part of British and Irish immigrants who found work in the city’s successful sawmill, agricultural, shipbuilding, and fishery industries.

In 1867, the year of Confederation, an exhibition was held on City Road, at the Victoria Skating Rink, a round building with a domed roof, that was used for roller-skating in the warmer months. For twenty cents, fairgoers could board a train to the Pleasure Grounds, near present-day Kennebecasis Park, to watch horse racing, a sport with as long a history in Saint John as exhibitions.

In 1880, Saint John’s main exhibition moved to a permanent location: the Barrack Green, a twenty-acre military training site on Sydney Street, in the city’s South End. Organizers constructed an exhibition building a hundred and sixty feet long by eighty feet wide, with an additional dome-covered front. Horse and cattle sheds were constructed, and a second, two-storey building, measuring two hundred feet by eighty feet, flanked by two towers, was added three years later, bringing the exhibition’s total floor space to ninety thousand square feet. The 1883 fair, held the year of the city’s hundredth anniversary, was dubbed the Dominion Centennial Exhibition. It featured Saint John’s first use of electric lights, which illuminated the grounds and buildings—until the dynamo machine failed and emergency gas lights had to be installed. Exhibits included the first centrifugal cream separator used in North America, and the unveiling of a drinking fountain donated to the city by the Polymorphian Club.

In April, 1889, members of the local board of trade, city council, and various other organizations formed the Exhibition Association of the City and County of Saint John, with a mandate to combine the best elements of the city’s various fairs and exhibitions. The new event debuted the following year, billed as Canada’s International Exhibition, though the press referred to it, unofficially, as the World’s Fair. It consisted of two sites: the Barrack Green land, where the midway, outdoor shows, and displays of farm machinery and livestock were located, and Moosepath Driving Park, located just east of the city limits. Moosepath was large, but the marshy ground on which it was built left horses to race in mud for much of the season. Nine hundred horse stalls and four hundred cattle stalls were added to the track’s existing stables for the exhibition, and trains connected the two sites. More than three hundred commercial exhibitors displayed their wares that year, including, W. H. Thorne hardware, Ganong Bros. confectioners, T. S. Simms brush company, and J. and A. McMillan stationers. Fifty thousand people attended, including Prime Minister John A. Macdonald and Governor General Lord Stanley and his wife, Lady Stanley.

Over the next two decades, the Saint John exhibition featured moving pictures of the Boer War, trampoline acts, merry-go-rounds, fakirs, palm readers, games of strength, and performers such as the Marvellous Marsh, who, twice daily, rode a bicycle down an incline atop a forty-foot tower before launching himself earthbound, headfirst, into a tank of water seventy feet away. Paid attendance reached eighty-five thousand by 1910, the year the renamed Dominion Exhibition was sanctioned the country’s official exhibition.

The Saint John exhibition was put on hold during the Great War, when the Barrack Green was turned over full-time to the military. It was revived in 1920, but suspended once more due to Canada’s entry into the Second World War, just as the 1939 edition was set to begin. This time, it would take a decade and a half for the exhibition to restart, after a fire on the barrack grounds in 1941 destroyed the exhibition buildings. In 1952, the exhibition association purchased the Moosepath land and much of the surrounding area at the base of what would soon be Forest Hills. The land was renamed Exhibition Park, and the fair, now known as the Atlantic National Exhibition, relaunched in 1954 and has been held in the same location every year since. Rides were provided by the Bill Lynch Show, the largest midway operator in the Maritimes, and eventually one of the largest in Canada. In the early days of Exhibition Park, before any permanent buildings were constructed, large canvas tents were erected to house the horticultural and livestock exhibits, and a rolling stage for live entertainment was built on the racetrack, facing the grandstand. Simonds Centennial Area was built in 1965, and hundreds of exhibitor spaces became available in the main building and the smaller wooden buildings surrounding the midway.

Traditional industrial fairs had been falling out of favour for decades, as magazines, newsreels, and television began reporting news of technological innovations at a much quicker pace. Local manufacturing became less cost effective, which meant smaller and fewer exhibits. By the nineties, the massive cultural shift caused by the Internet made events like the A.N.E. even more antiquated.

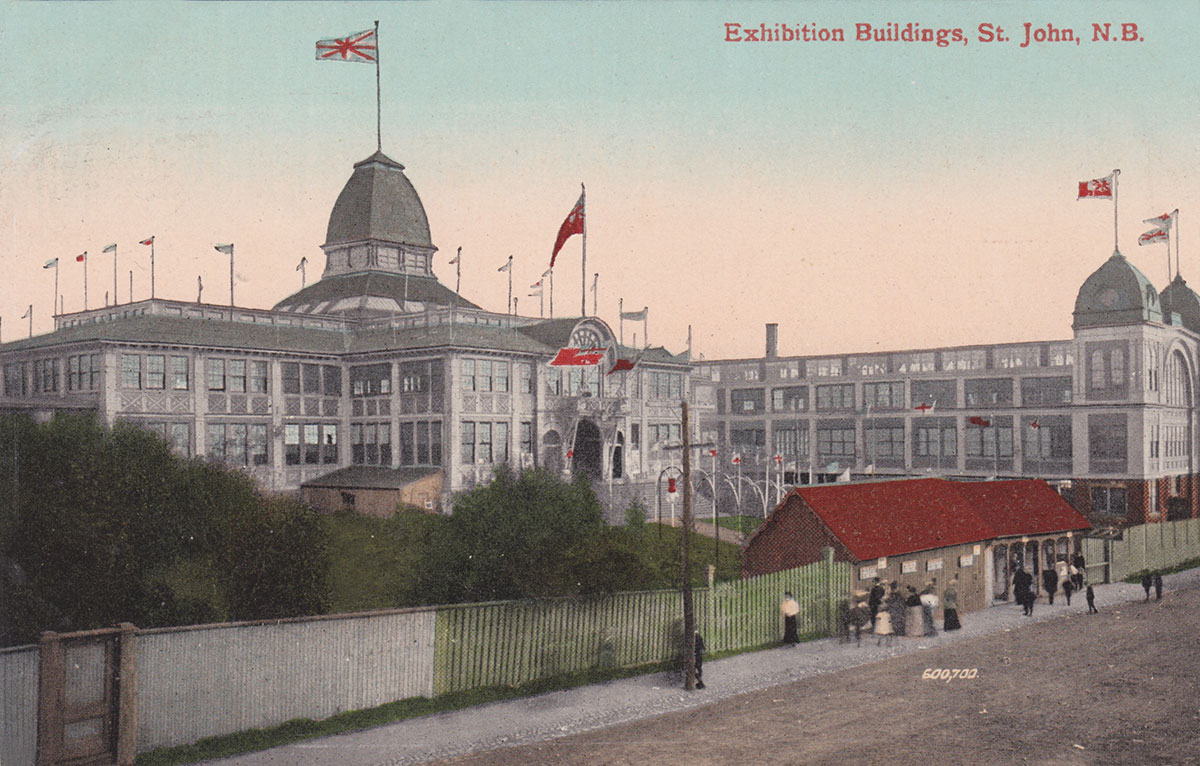

A hand-painted postcard of the Barrick Green exhibition buildings.

An aerial view of the grounds during the 1957 exhibition.

I left Saint John in 1991, but visit frequently. Over the years, I’ve observed the changes to the exhibition grounds, most of which took place in the early nineteen-nineties. A Cineplex movie theatre sprung up partially on the site of the Simonds ball field not long after I moved away. The ice rink and exhibition buildings were demolished soon after. A succession of fast food establishments—including, fittingly, an A&W and a McDonald’s—were built on a field formerly used for parking. The grandstand was demolished, and many of the barns are now empty.

I visited the city this February. Before I arrived, I contacted Frank McCarey, the current president of the Saint John Exhibition Park Association, to see if he’d be willing to talk to me about how the exhibition had changed over the past quarter century. On the morning I pulled up in front of the association’s office, the city was still digging out from its third major snowstorm in about a week. Snow banks along some sidewalks were piled six feet high, but the exhibition grounds, somehow, showed no trace of snow or ice.

McCarey told me the association began leasing off parcels of land in the nineties because “the finances of the association had become absolutely desperate.” The exhibition had always been a loss leader for the organization, but by the nineties it was losing more than usual. “Attendance was dropping,” McCarey said. “How many kids now haven’t been to Disneyland? The exhibition was a pretty special time, but it just doesn’t hold the same attraction it did at one point.” Much of the association’s income came from harness racing, which was extremely profitable for decades. “Harness racing is basically dying everywhere,” McCarey told me. “When you look at it, the attraction was the gambling aspect, and government-sponsored lotteries sort of decreased that attraction. I think next year the only harness racing in the province is going to be here in Saint John.” The association pitched the idea of building a racino—a racetrack with video lottery terminals and other electronic games—when the provincial government solicited casino proposals more than a decade ago, but a similar proposal put forth by the neighbouring city of Moncton won out in 2007. Now, plans are underway to install a cricket field in the centre of the raceway.

The exhibition buildings and arena reached the natural end of their lives at the same time the association’s finances became dire, and the grandstand was condemned by the time it was torn down, in 2003. Once the association became solvent again, about a decade ago, it was able to begin thinking about rebuilding. The board “made a decision that, instead of putting up a building that we’re going to use once a year, let’s see if we can leverage it to something that’s more useful to the community,” McCarey said. The group recently donated a portion of its undeveloped land—which McCarey values at one million dollars—to the city, for the construction of a field house, which will contain two indoor soccer fields. It also donated an additional four million dollars toward building costs. In return, the association will have use of the building for one week a year during the exhibition.

“We’ve seen attendance go up in the past couple of years,” McCarey said. “We’re trying to change how we market it. We stopped charging for admission and that’s brought more people out. It’s sort of leveled off and it’s been going great since then. What happens now is people will come out one night to the exhibition. It used to be people would come out every night. We’ve got it budgeted next year at a cost of about two hundred and fifty thousand. We’ll generate about a hundred thousand and lose about a hundred and fifty. The intent is not to make money on the exhibition. The Ex never made money. The intent is to do something for the community.”

Fred Tobias and Cindy Crawford work the Red Cross booth in the late seventies.

In August of 2016, I returned to the Atlantic National Exhibition, now known as the Saint John Ex (“We decided to call a spade a spade,” one organizer told me), for the first time in more than a quarter century. I met my friend Andrew at his parents’ house, down the street from my own. We had no incentive to scale a fence now that admission was free, but I convinced him we should at least retrace our childhood steps through the field. We regretted our (my) plan fairly quickly, when we became entangled in tall grass and weeds. Without a ball field, there seemed to be little reason for the rutted paths to stay rutted, or maybe there were simply fewer children in the neighbourhood than there used to be.

The layout of the midway had changed significantly, but I soon realized the acreage reserved for the exhibition itself was the same, even as the land surrounding it now had other uses. A newer building that I remember being constructed in the early eighties now housed exhibitors, amateur arts and crafts, and the onstage entertainment combined, while some of the decommissioned stables displayed prize-winning vegetables, flowers, and livestock. A smaller building featured a mom-and-pop grill. There was still a collection of rides for children and adults, including the Tilt-A-Whirl, a Ferris wheel, and the infamous Zipper. The bingo tent was largely unchanged, though proper markers had replaced the corn. There were still games to throw and shoot things at, with prizes that looked no more appealing than they had years before. Vendors who once sold studded wristbands now peddled hash pipes. Some of the midway foods available at the Canadian National Exhibition found their way east, including deep-fried Oreos and a knockoff of Tiny Tom doughnuts. Throughout the grounds, show cards hand-lettered by Norman Jackson—a local artist know for his panting In This Decade, depicting John F. Kennedy overlooking the moon landing—pitched everything from a baby show to a high-dive act to a poultry competition.

I offered to take my mother to the exhibition—a reversal of our previous roles—and we spent an evening watching the stage show. Before that we walked around the grounds. She refused to play bingo with me, but I’m confident this was due to lack of interest, and not a lingering bitterness. She commented that the exhibits were nothing like they’d been in my father’s day. There was definitely less to see and do at the Saint John Ex than there’d once been, but the organizers seemed to understand that times had changed, and adjusted accordingly. The Ex wasn’t breaking new industrial ground, and it wasn’t offering any special sort of fun that couldn’t be had elsewhere. But it was homey and genuine, and entertaining in a new and different way.

I returned another evening with my friends Peter and Pamela. We passed Cover the Spot and I told Peter about the week-long defeat I’d suffered years before. He goaded me to play, and handed the carny some money on my behalf. I lost Peter’s money and a bit of my own, but this time I had the willpower to walk away before things got out of hand. When the carny—who went by the name of Bones—tried to coerce me to continue, I told him I’d lost enough money to the game three decades earlier. I jokingly suggested it probably had been him who’d taken it from me.

“How old are you?” he asked.

“Forty-three,” I said.

“I’ve been running this game for thirty-four years!” he cried. “It was me!”

The main gates, 1978.

A midway carny, 1978.

The author meets Rooty, 1976.