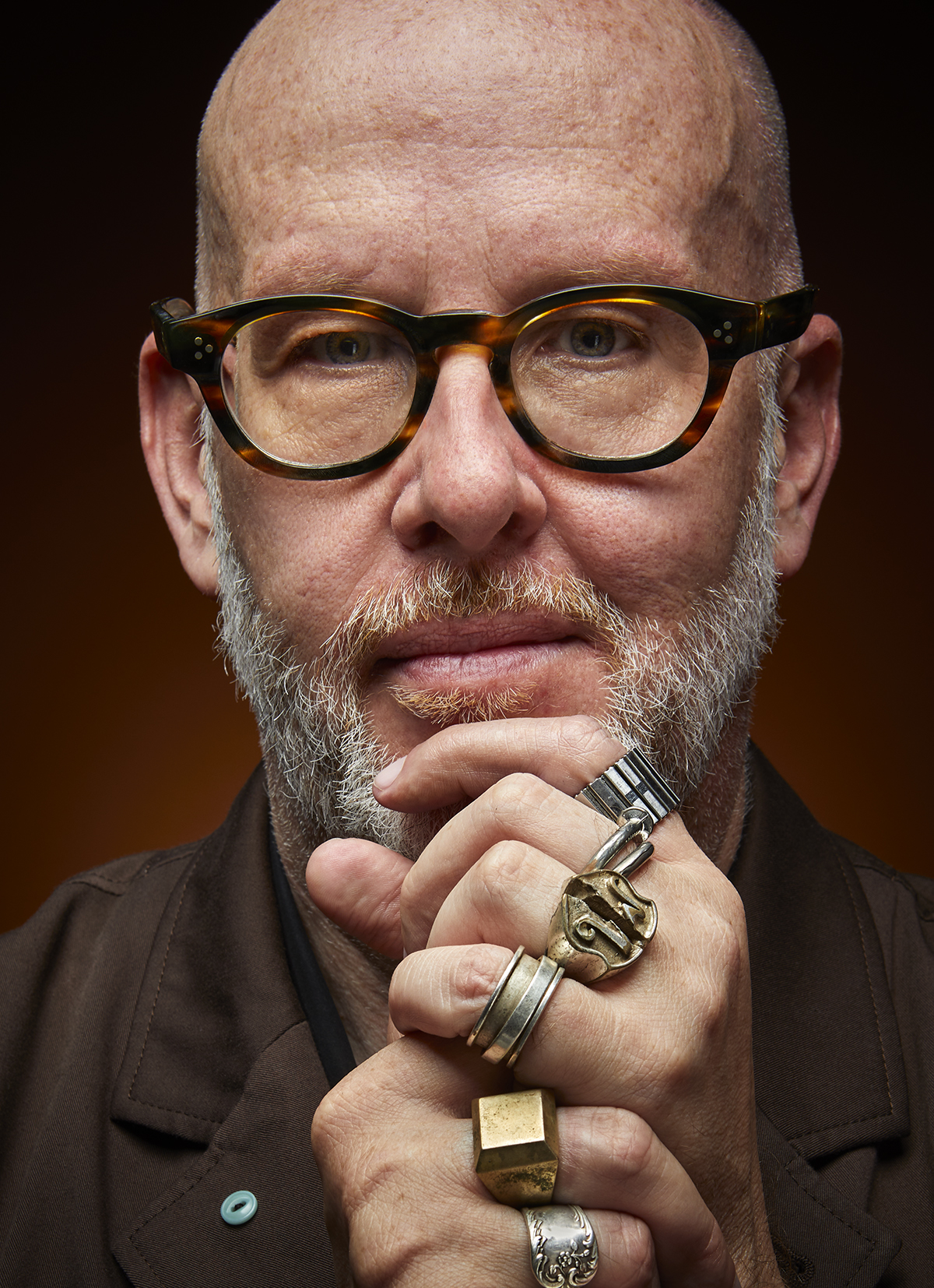

Derek McCormack was his usual self-effacing self this past February, when he took part in a Zoom conversation with the journalist Nathalie Atkinson, in support of his latest book, Judy Blame’s Obituary, a collection of his non-fiction writing on fashion. McCormack, who is fifty-three but still has a slightly boyish look, despite his close-cropped hair and white beard, dressed in keeping with the subject matter, in a rubberized Jean Paul Gaultier shirt he said he bought in the eighties. Not that you’d know it. Slumped far down in the frame, he revealed little below his neckline, letting his backdrop of vintage Halloween decorations and carnivalia take up more space on the screen than he did. “There’s nothing that could get me to stand up and show you any more of this shirt,” McCormack told Atkinson. “It’s like a halter top on me at this point.”

Judy Blame’s Obituary is McCormack’s ninth book since 1996, and the second published in just over a year. In 2020, he released Castle Faggot, his latest comically dark horror novel touching on various aspects of pop culture—in this case breakfast cereal monsters, the fashion world, and Rankin/Bass stop-motion TV specials—that may or may not be the third (or fourth) part of a potentially mislabeled trilogy. This uncharacteristic proliferation resulted in a number of online appearances for McCormack, including launches for each book and a lecture on dolls for Toronto’s Bata Shoe Museum. Although McCormack likes to put on a sad-sack loner persona—and it is, in large part, a put-on—he’s ready to perform in front of a live crowd again. “At first I thought, ‘This is great. I don’t have to leave my apartment,’ ” he said. “I would get quite into it. But then there’s no one after to tell you how you did, or to get a drink with, or to go out for fries with. So I started to have these little tricks before I would do an event. I would leave TCM on my TV at a low volume, so when the hubbub just dies, I wasn’t totally alone.”

Over the past year, McCormack and I spent quite a bit of in-person time discussing his writing career—conversations that were equal parts entertaining, given his playful cattiness and self-deprecation, and frustrating, for his long-held resistance to answering questions factually. Our talks were inspired by the recent twenty-fifth anniversary of Dark Rides, his debut short story collection, but also by the fact that McCormack’s career is such an interesting case study of a small-press author who came of age in Toronto’s vibrant nineteen-nineties small press scene—one who received a not insignificant amount of mainstream attention early on, despite his work falling far outside the mainstream. The stories in Dark Rides were inspired by McCormack’s youth as a gay teen in small-town Peterborough, Ontario, where his parents ran a local department store, and he fell in love with the writings of Baudelaire, Rimbaud, and Burroughs, while devouring the fashion and pop culture articles he found in the pages of magazines like The Face. Dark Rides is set in Peterborough in 1952. It features various characters—many of whom are named Derek McCormack—who walk through life with an unearned arrogance, despite, or perhaps as a result of, a näivety that continually sees them humiliated either verbally or physically by rural locals who love nothing more than torturing those they view as different. “I was just showing readers the dangers of working on a haunted hayride or shopping at a joke shop or going to some honky-tonk saloon underage and getting hosed in nineteen-fifties Peterborough,” McCormack said. “So I guess it’s a cautionary book.”

Despite being published by a Toronto-based micro-press, Dark Rides garnered a decent amount of, largely positive, reviews. “I was received surprisingly well,” McCormack said. “I was pretty green, in the sense that I had no expectations. Dark Rides was distributed by a really great distributor in the States. In Canada, it was slow, but once it got reviews in the U.S., Canadians started calling. I was on Imprint, a literary show on TVO. I remember that because the first question was, ‘Do your parents know you’re gay?’ That was the kind of question you got at the time. But you didn’t get shelved in Fiction, you got shelved in Gay Interest, at the back of the store. The only books you could really get published by a mainstream press as a gay person were AIDS memoirs or coming-out books. That was all straight people wanted from you.”

The height of McCormack’s early Canadian fame was, arguably, a 1999 Globe and Mail article titled “Book Boys”—a puff piece that touted a group of then young authors—Andrew Pyper, Russell Smith, Evan Solomon, and McCormack—as “Toronto’s literary Brat Pack.” The group is described as having “lifestyles and agendas . . . a far cry from Pierre Berton and Peter Gzowski” and running “the cocktail circuit in packs, standing out in designer trainers and Prada knockoffs amid the rumpled-cardigan masses. Beautiful, cocky, determined to succeed and, like most packs defined by age, attitude, haircuts and hormones, slightly ridiculous.” McCormack is said to be “probably the least recognized of the group, [but] the others treat him with reverence for his experimental style”—all of which he still bristles at today. “Have you ever heard a worse description of me?” he said. “Let’s go through that. I didn’t wear trainers. I didn’t wear knockoff Prada. I didn’t wear knockoff anything. I was not a party animal. I was not Spuds MacKenzie. There’s no resemblance to me at all. And no one has ever treated me with reverence.”

Over the next decade, McCormack released another story collection, Wish Book; a carnival-inspired collaboration with the poet Chris Chambers, Wild Mouse; the non-fiction volume Christmas Days; and two novels, The Haunted Hillbilly and The Show That Smells, not to mention several objects d’art though the Toronto press Pas de chance. With The Haunted Hillbilly, he moved his setting away from nineteen-fifties Peterborough and to a stylistically fictional land of his own creation, mixing real-world icons from the realms of country music and fashion with a variety of literal (often gay) monsters. McCormack continued to earn mainstream press, but a major deal remained elusive.

“Even though that Globe article was awful and depicted us as dipshits, it was weird to be a gay writer with three straight writers who were getting a lot of press and had big book deals. It didn’t make sense that I was there,” McCormack said. “There was a period when everyone was getting signed to agencies and big deals were being made, and gay men never made those deals. We were still considered outsiders. For all the great groundswell of CanLit and the money infused in it and the agents and parties and deals, you didn’t get those if you were a fag. But then something really weird happened: gay lit sort of came into its own. In a short period of time it became recognized. It could go in Fiction. But then, in a heartbeat, it was boring, it was passé, it was too prissy, it was old fashioned. I think the moment came after gay stuff hit the mainstream in sitcoms and movies. Gay became normalized, but it was this super-sanitized version of gayness. There was a moment in the eighties and nineties when people were interested in transgressive literature. I had always been lumped into that. It’s ridiculous, because transgressive literature was always defined as dirty-ass stories of urban living, drug use, prostitution, recklessness, and I was never like that. I was always writing about the fifties in small-town Canada or in Nashville at the Opry. But I guess there was enough finger fucking and rimming and shit that people saw it as transgressive.”

Not long after his fortieth birthday, McCormack began experiencing pains in his stomach. He eventually was diagnosed with peritoneal surface malignancy, a cancer that attacks the tissue covering the abdominal walls and organs. Thankfully, a recent mid-life health kick had left him strong enough that doctors were able to try an aggressive surgery. In early 2012, McCormack entered Mount Sinai Hospital, in Toronto, for a daylong procedure, during which surgeons opened him and essentially lifted and scrubbed each organ, as well as his abdomen walls. McCormack’s spleen, as well as parts of his liver, bowel, and intestine, were removed permanently, along with the lining of his abdomen. Doctors then briefly filled his abdomen with a warm chemo solution, before sewing him back up. Potential complications resulting from the procedure are plentiful: for example, because the abdomen lining will not grow back, doctors need to ensure organs don’t attach to the walls. (McCormack’s bladder did end up attaching to his abdomen, making him prone to infections.)

Recovery is as equally, if not more, unpleasant than the surgery. “I was in the I.C.U. for two weeks,” McCormack said. “The surgery also shuts down your digestive system, so they have to hope it starts up again. With me it took about eight days. And the delirium. I didn’t sleep for weeks. I was suicidal. When I had my eyes open there were beetles crawling all over me, there were outlets speaking to me, and I thought I had wind in my clothes. I thought someone had stolen my teeth and put British teeth in. Your body diverts all the glucose away from your brain to heal the body, so your brain is a damaged little animal. I stopped talking. And when I did open my eyes I’d say, ‘I can’t do this.’ Eventually, I started to eat, started going on walks. I moved back into my own apartment. It did wonders for my brain to be there.”

Because peritoneal surface malignancy is extremely rare and usually forms in patients over the age of sixty, there isn’t a lot of information on survival rates for someone McCormack’s age. Around fifty percent survive for five years. McCormack has now survived for ten.

McCormack is keenly aware that this real-life experience mirrors many of the fictional horrors in his writing. In the short story “Wish Window,” a department store window dresser uses a display to expresses his anger after being diagnosed with cancerous tumours, while the country singer Hank Williams dies a slow, disturbing death across the pages of The Haunted Hillbilly, just to cite two examples. “It all makes sense,” McCormack said. “When I was a kid, I started bleeding in my pee, and I had maybe four or five exploratory surgeries to see if I had cancer. I didn’t, but it still gave me this deep expectation that it would be found one day. I was a terribly ill child, and I also grew up really openly gay in a space where that was considered a sickness—I didn’t think it was a sickness, but obviously I developed this anxiety about being sick in other ways, which comes out in my books.”

McCormack’s first post-cancer book, The Well-Dressed Wound, a Civil War–era story featuring Abraham and Mary Todd Lincoln facing off against the Devil disguised as the Belgian fashion designer Martin Margiela, is not only sparser than his earlier novels—many pages are mostly, if not entirely, blank, and several others feature little more than exclamation marks—it’s also angrier. Two pages are made up almost entirely of the word “faggot,” and everything, living or inanimate, is covered with AIDS. “The Well-Dressed Wound is my cancer book,” McCormack said. “I really wanted to write a book about dying and cum and shit and an angry screed, which I did. I think it’s the sparsest book because I had to write more of it in my head when I was lying on the couch. I did not have the strength to sit up at a computer, and I didn’t often have the strength to write, so it repeats a lot and it’s rhythmic. I could only hold things in my head long enough and get them on the page and then think of the next page. Someone read Castle Faggot and said, ‘Oh it’s the angriest book, but it has the most emotion,’ but I think The Well-Dressed Wound is by far the most emotional and the angriest of the books. There’s very little time to stop and laugh in The Well-Dressed Wound. It’s just outrage after outrage and death after death.”

If his latest novel, Castle Faggot, feels like a return to form, it’s because it was written largely pre-cancer. Originally a novel called Rue du Doo, it placed McCormack-styled versions of the General Mills Monster Cereals characters in a Rankin/Bass-type setting. But the book ended up short, even by McCormack’s standards, and was eventually shelved. “I thought, Should I add these other ideas? Should I write other things? And then I got cancer, and when I was recovering the book didn’t really interest me at all. Then, having survived and having had The Well-Dressed Wound flop, I thought, Oh shit, I’ve got to write another book. Oh my god, I have this thing here. I had someone read the Rankin/Bass section and they said, ‘For something that was really short, there were a lot of boring parts in it,’ and they were right. There’s a general frustration with me as a writer: after twenty-five years, why can’t I write the idea I want to write? Why do I always cut everything out? Why do I always not pursue things to the end? There’s so much fun, rich nostalgic resource material and such personal feelings about those monsters. I’d tapped into it a bit, but I wasn’t maximizing my own pleasure, which is what I tried to do in the end.”

Ironically, the anger and outrage McCormack fed into his recent novels was fed back to him by some in the gay community. While the multiple instances of “faggot” in The Well-Dressed Wound managed not to draw too much public ire, its appearance in the title of his latest novel did. After years of being embraced by the gay community, McCormack was suddenly face to face with a new L.G.B.T.Q. generation that didn’t agree with his long-held ownership and love of the word. Several bookstores refused to display Castle Faggot, and it was removed from Amazon several times, owing to a combination of customer complaints and algorithm flagging. “I hear blowback from young queer people who find my take on these things distasteful, but I also think they’re just generally not interested in a middle-aged white gay writer,” McCormack said. “I don’t blame them. I think that, at best, we’re just super boring and, at worst, we’re spoiled or privileged.

“I think I got reinstated on Amazon because my publisher, Semiotext(e), is distributed by M.I.T. Press. But a couple of places were supposed to run reviews and didn’t. Two of them were gay and lesbian publications. That said, it’s been much less flak than I would expect. Castle Faggot had the fewest reviews I’ve ever gotten but the best sales. Part of that is distribution. I got interviewed by a kid who bought it at his bookstore in Jerusalem. I got a note from someone who bought it from the gift store at the Tate. I think the fact it had that title made it taboo. And I have a sense that word may be becoming more prominent again thanks to me. Just the other day on the street some people called me faggot and I thought, Oh, they loved my book.”

Despite initially claiming he was done with his past characters, McCormack currently is working on a book that returns to the world of country music. “I can’t even picture there being another book like my older books,” he said. “It’s going to be much less writing and more visuals, but the visuals will not be copied and they won’t be black squares, they’ll be things I made. The new book I do with images will be set in Nashville, in the country music world, and it’s going to visit all the characters in the country music novels, but it’s going to be like a wrap-up. I feel like there are a few things left I haven’t desecrated in country music, and I’m just going to get in there and do it. I love writing about those country and western characters because they remind me of growing up listening to that music. There’s also so much nostalgia: there was nostalgia for a period I wasn’t born, there was nostalgia for a period my grandparents talked about, there was nostalgia for a period my parents lived through, and now I have nostalgia for the period when I was writing those things: that period when I wrote The Haunted Hillbilly and went to Nashville and drove around. I’m nostalgic for that youth and that freedom. And what I want to do with the writing has changed. My future books will all be attached to something I make. I’m not good at making things. But if the good Lord or Satan gives me a few more years, I would like to get good at making things. I can see some of them not being books at all. I can see one of them being a magic show that has no publication. Some of these things in my head look more like a craft category at a rural fall fair. I’ve been publishing for twenty-six years. I still like publishing, but at some point you’re like, How can we vary this? My art friends have dragged me slightly into the art world, and I love watching people make things. It seems to me so gratifying and something you can do despite your bad health days.

“My idea for my last book is set in a miniature train, and I basically want it to be a cycle where I go back through the sites of all my books. It’s a book about travelling through this landscape, where I keep returning to my ideas over and over, which is what all my books have been anyway. I really wanted to literalize the idea that I keep returning to the same things, kind of as a goodbye. There’s going to be a serial killer on the train. And then I think someone might kill me. It’s either a return to familiar ideas or admitting I only have one idea.”