Hi Mom,

The cold’s all right and the work itself isn’t too bad, but the sap is driving me crazy. I come home feeling like my skin is covered in it and nothing gets it out of my clothes. I can’t stand touching my gloves. Too sticky. But it’ll be over in a few weeks and the pay is decent.

Russell is doing well, thanks for asking. This Christmas tree gig is right up his alley. Please try to remember to call him “he.” I know you try your best but

Eli taps his spacebar several times then deletes the unfinished thought.

Please try to remember to call him “he.” If you come down for a visit we should all get dinner together—he looks really different these days. Lost some weight and grown a beard. Seems to be staying out of trouble.

Tell Aunt Barbara that I won’t make the party, but I’m driving upstate the next morning—got a few days at the restaurant off in exchange for working Christmas Eve. Will be sure to visit her while I’m around. Please take care of yourself, and let me know if you need anything. E-mail works best.Love you,

Eli

Eli hits Send and checks the time in the corner of the screen. He rummages through his closet until he finds something untouched by tree sap.

It’s exactly eight when he pulls his station wagon into a parking spot at the restaurant. He steps out into a puddle of sludgy half-snow, what TV weather forecasters gave the much-too-cheerful description “wintry mix.” Eli extracts his boots from the mess and trudges on toward the kitchen.

The restaurant, Francesca’s Inn, is a beautiful building from the early nineteen hundreds that has been Frankensteined with mismatching additions over the years. The upper floor is a family restaurant; there’s an adults-only bar downstairs. Eli is grateful to work in the back, where he doesn’t have to deal with drunks. He walks through the employee door and hangs up his coat. His cheeks are flushed as he ties his black apron around his waist. One of the waitresses—Stacy, maybe?—is on her break, hanging out in the kitchen, flirting with the cooks. She sees Eli and waves at him. He nods at her and heads toward the dishwasher. Eli is boyishly handsome, but never got the hang of flirting.

Ninety minutes into his shift, Eli has heard “Jingle Bell Rock” at least three times. He slides another tray of dishes into the machine and pulls down the top. There’s a lull at the moment, and while the dishwasher runs, he checks his hands. The cracking skin around his knuckles reminds him he needs to pick up lotion on the way home. He wonders if Russell has any.

Eli feels a vibration on his hip. He’s not allowed to answer his phone at work, but he quickly checks the screen. It’s his mother. He lines up some more dishes and puts them through the washer, moves the clean dishes down the line. He waits for the phone to chime, telling him his mother has left a voice mail. It doesn’t. She hasn’t. Instead, the vibrations start over. She’s calling twice in a row—he wonders if something is wrong. He’s lining up dishes on autopilot. He doesn’t notice the hair, not at first.

Eli picks up a plate and yells, “Shit!”

It’s covered in long, dark, thin hair. He looks around in a panic, but no one has seen it yet. One of the cooks shouts back, “Is everything O.K.?”

“I, uh, burnt my hand,” Eli replies, “but not too bad.”

Eli tries to scrape the hair off of the plate and into the garbage, but the mound does not get smaller. Thin black hair begins to pile up and over the edges of the plate, growing longer and more tangled. He drops the whole plate into the trash. The phone is still buzzing. When he reaches into his pocket to turn it off, he touches a clump of hair. It’s wet, and it sticks to his skin, and Eli’s heart is pounding as he tries to trash the hair faster than it can appear.

The edges of Eli’s world start to blur and dislodge. He digs his fingernails into his palms, willing the hair to go away. He tells himself it’s not real, that he’s going to open the dishwasher and finish the dishes and it is going to stop. Eli’s boss tolerates, but doesn’t like him. He needs to focus to keep his job. When he counts to three, the hair is going to stop.

One. Two. Three.

Hi Mom,

I called Dad and told him. He sends his best wishes. How long do you think you’ll be staying at the hospital? If I can switch shifts this Wednesday, I could drive up and visit. Let me know. I’ve attached pictures of the apartment. It’s definitely big enough for two. Before Viola left I slept on the futon for

Eli remembers he never told his mother that his girlfriend was living with him.

It’s definitely big enough for two. Quiet building and there’s an elevator. Just an option—we can talk about it whenever you feel ready. Get some rest!

Love you,

Eli

“That’s fucked, dude,” Russell says to Eli the next day. “Your mom’s not even that old. Is it, like, broken broken? Hair fracture or, like, does she need a whole new hip?”

“I guess I don’t know,” Eli says. He drags and piles branches while Russell takes his first cigarette break of the day.

“Well, that’s pretty fucked.” Russell adds between puffs. He’s not supposed to smoke on-site, but the wood chipper is way out at the edge of the farm. He usually doesn’t get caught, and Eli doesn’t say anything. He’s a little impressed that Russell can operate a lighter with those big, clumsy gloves crusted in sap. They’re identical to the ones Eli wears—Eli bought them packaged together.

They hear the boss call out to them and Russell quickly stabs out his cigarette and throws the ashy remains into the woods. They hustle past rows of nearly identical fir trees. When a customer makes a selection, they cut it, drag it, wrap it, hoist it, and tie it to the customer’s car. There’s also a delivery option, but no one ever takes it. It costs extra, and in this part of Maine everyone owns a car. At least, everyone except Russell, who recently moved back from New York City. Eli drives him everywhere, just like in high school.

“So, you heard from that Viola chick?” Russell asks as they drag the tree toward the wrapping station. It’s a tall one, and fragrant. It’s one thing Eli likes about the job: the smell.

“She’s not—no. She’s gone,” Eli says. “Over. Like, not-speaking over.”

Russell sucks his teeth dismissively.

“What was her deal again?”

“She got an internship, down in Rhode Island.”

Eli carefully lines up the trunk of the tree in the packager, a little metal hoop rigged up with bright orange mesh. “And, you know, it wasn’t going that well.”

“That’s such bullshit, internships. It’s like they started passing laws about volunteering and they had to think of a new, hip word for working for free. It’s like you get all this student loan debt—”

“Hey, pull it?” Eli asks.

Russell pulls the trunk from the other side of the hoop, and the big, unruly tree comes out, tightly bound in the shiny, criss-cross orange plastic. The vibrant shade of the mesh reminds Eli of Viola’s hair when they first met.

Eli squints at the wrapped tree, seeing it quiver and bulge. Something is moving inside of it. He hears a familiar whining sound and hooks a finger through the mesh, tugs on it as if to test its strength. Russell cuts it off of at the hoop and just before he ties it closed, a black cat shoots out of the end of the tree. When Russell doesn’t react—doesn’t see what Eli saw—he knows that it was Viola’s cat, Wednesday. Eli feels nervous sweat threatening to leak through his heavy layers, but he gives his head a shake and gets back to the job.

They hoist the tree up onto the customer’s minivan and tie it down. The customer—a pale blond woman who looks too young to be the mother of the three kids dozing in the van—slides Russell a tip. He thanks her with an “aw shucks” and a wink. She smiles at him for a moment too long before leaving. Russell, unlike Eli, is a masterful flirt—especially with women, even though he has no interest in dating them. Perhaps because he has no interest in dating them.

They head back out into the trees, looking for debris to drag to the wood chipper. Russell continues as if the conversation was never interrupted.

“So, it’s, like, you go into all this debt to go to college, because your whole life that’s what they tell you need to do to get a job so you can buy a house or whatever. Then you work for free, because now that’s what you need to do. You work your ass off in school, and then you work your ass off for free and then when someone will finally pay you, you’re so broke that you’ll work for any bullshit rate. And people with actual good jobs call people our age lazy, but . . .”

Russell rants on, but Eli is focused on something far away. He’s thinking about that mesh, about Viola’s neon-bright orange hair, about lacing his fingers through the mesh, through her hair, and he sees a flash of that bright orange moving between the rows of trees. Eli feels the ground underneath his feet shifting, the memory trying to pull him inside of it. Instead of letting himself slip down, he steps forward. He can see her—Viola, laughing as she runs. Then Eli sees himself. He sees Eli chasing Viola. Eli follows.

He loses himself and Viola for a moment and walks faster, jerking his head around to peek through the jungle of evergreen branches. There: Eli has caught Viola by the arm and they’re kissing now, they’re reclining onto a bed that isn’t there. Eli is touching Viola over her jean skirt and she’s saying, “No, not there,” and he says, “Show me where,” and she guides his hand with hers. She takes a finger into her mouth and bites it. The Eli that’s watching remembers this is the first time they had sex, after they made out in the car until it got too cold and she raced him up the stairs. Eli is seeing this moment from behind a row of unclaimed Christmas trees, but he also sees Viola from inside that memory. He lets himself sink inside the heat of this playful first time and the heady feeling of blooming love. His face is brushing against her skin; he doesn’t know why it smells like pine.

When Russell touches him, the moment evaporates and Eli feels as if he’s been yanked up out of deep water. He gasps and shudders, and Russell pats his shoulder.

“Losing time, man?” Russell asks. That’s how Russell talks about what happens to Eli.

“Yeah,” Eli says. “Thanks.”

“Come on. Somebody else needs a tree.”

Aside from the two years Russell spent in New York City, Eli and Russell have been inseparable friends. In high school, everyone thought they were a lesbian couple, especially since Russell dressed and acted so butch. It was Eli who came out first, though, and Russell was one of the first people he told. Russell had reacted with disbelief, and with a weird kind of anger Eli couldn’t name or place and certainly hadn’t anticipated. Two days later, Russell apologized and told the truth: he was trans too, and was convinced their parents would never believe them if they both came out at the same time. His devastation was short lived: But fuck what my parents think. It’s just one more thing they won’t get about me.

Still, they were careful to tell a story that wrapped the coincidence up in fate. “I guess that’s why we related to each other so well,” Eli would tell his mother. They chose different therapists and doctors in different neighbouring towns and didn’t mention each other to them. In their backwoods part of the state, it was easy to imagine a doctor with two young patients requesting hormone replacement therapy deciding it was a trend instead of a need. Coming out more or less together wasn’t all bad, of course. They could do each other’s shots when one of them wasn’t feeling brave. They went shopping together, celebrated each other’s milestones, swapped horror stories. And Russell helped Eli stay grounded in the present whenever he started to lose time.

Eli settled in Maine, close to home, pretty early. Their hometown inspired constant anger in Russell, who instead floated across New England for a few years. He started college in Vermont and then quit. He grew weed in New Hampshire until he almost got busted. He lived and worked in a motel in the rural Berkshires. He was a barista in Boston, a tattoo apprentice in Providence. He worked for six months at an alien-abduction-themed business just outside of Hartford, Connecticut—Eli couldn’t understand if it was a gift shop, some kind of museum, or just a weird tourist trap. When that place closed its doors, he hopped on a train to New York, met a guy named Dylan, and disappeared for two solid years. Eli only knew he was alive because of the occasional cryptic e-mail he would send: “Laptop stolen. Public computer at the NYPL. Life’s fucked, huh?”

Eli hands Russell a bottle of ibuprofen while they’re at a red light. Russell thanks him and pops one into his mouth, swallowing it without any water. On the radio, bells are ringing and Darlene Love is begging her baby to come home.

“Lotion’s in the glove compartment if you want,” Eli says.

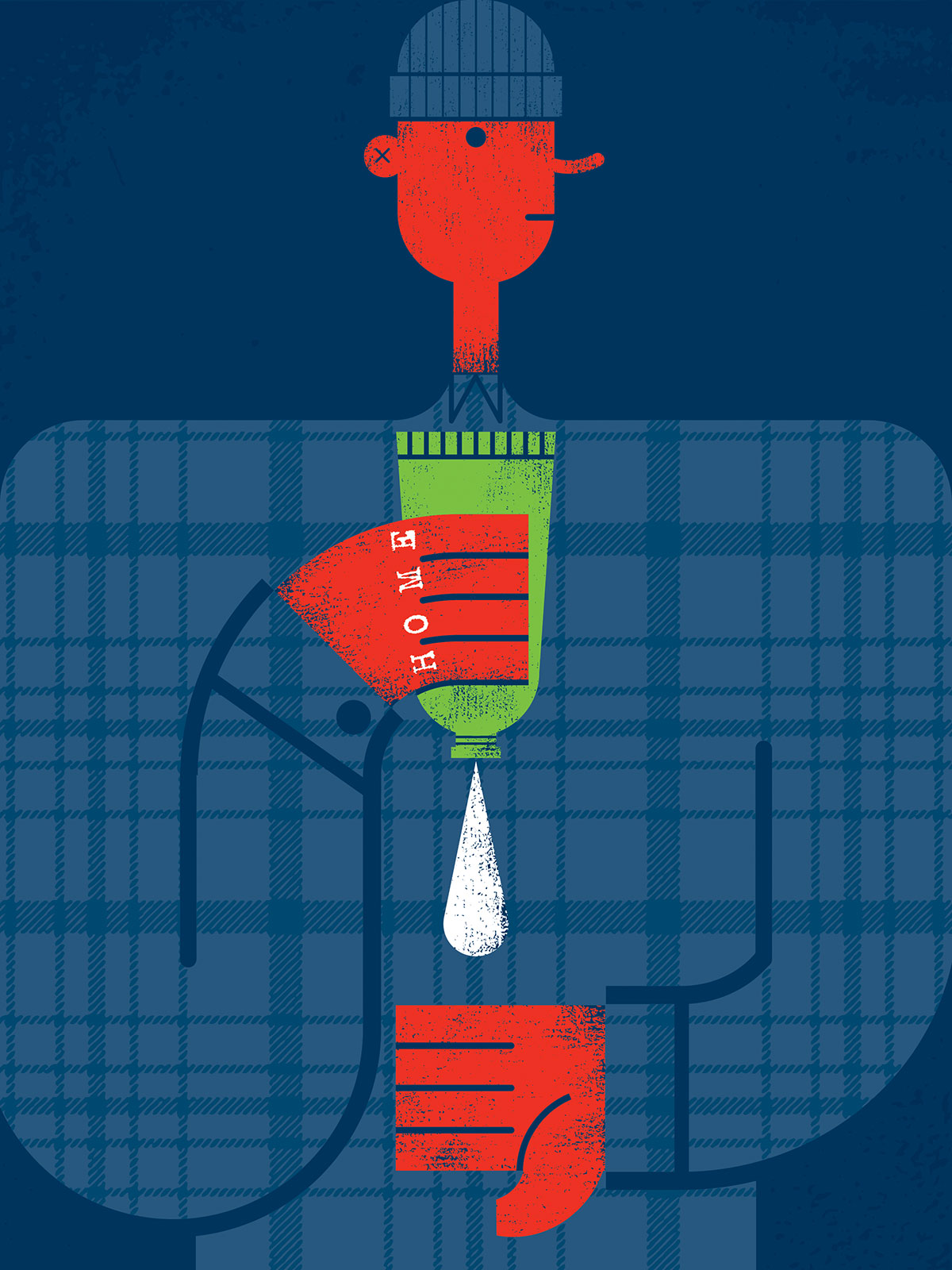

“Definitely,” Russell mumbles and reaches forward. He pulls out the lotion, squeezes a bit too much into his palm. He rubs it into his sore left hand, where his knuckles read: l-e-s-s. Then into his right: h-o-m-e. Russell takes stock of where the skin has cracked and frowns.

“So Saturday’s Christmas,” Eli starts.

“Yeah?” Russell replies in a tone that lets Eli know he has just said something incredibly dumb.

“Do you know what you’re doing yet?”

“For Christmas? Family bullshit, probably.”

“I meant after,” Eli says, turning down the radio. “Thursday’s our last day.”

Russell says nothing for a moment. Then: “Maybe ask Mary if there’s other stuff I could do for her.”

Mary is the woman who owns the tree farm. Eli knows she’ll say no—she has a day job. The trees are a side income.

“I could ask at Francesca’s,” Eli says.

“Yeah, I guess,” Russell says. “But I can’t keep staying with my parents.”

“Rent’s pretty cheap around here,” Eli says. They drive past an elaborate Christmas light display that has just flickered on in someone’s yard. Russell points at it.

“All this stuff looks so stupid with no snow on the ground.”

“Yeah. Global warming, maybe.”

“Maybe I’ll go back to New York,” Russell chimes, as if this is a positive option.

“You’re kidding,” Eli says. When Russell doesn’t respond, he asks, “Where would you stay?”

“With Dylan, probably,” Russell mumbles.

Eli flexes his hands, squeezing the steering wheel. Russell pretends not to notice the discomfort.

“He kind of called.” He shrugs.

Eli has never met Dylan, but he doesn’t like him. He doesn’t like the way Russell talks around him, avoids questions about him, like he’s a secret. Eli suspects Dylan is the reason Russell stopped talking to his friends. Eli suspects Dylan is the reason that, when Russell showed up so suddenly at his door again in October, he was skinny and jumpy and willing to move back in with his parents. Eli suspects that Russell’s laptop wasn’t stolen. Eli has never asked if Dylan ever hurt Russell, or took Russell’s money. After growing up with him, Eli has learned not to press on the sharp places.

Instead he asks: “What did he say?”

“Oh, he’s sorry, blah blah blah. Misses me.”

“Did he say if he was sober?”

Russell shrugs and stares out the window, his stony face telling Eli not to ask anything else.

Eli grabs the ibuprofen and his water bottle, puts the pill on his tongue, and washes it down. He picks up the lotion Russell left on the passenger seat. He pauses, feeling as if he forgot something, then puts the bottle back in the glovebox and heads inside.

As Eli climbs the stairs toward his apartment, the forgetting feeling strikes again: something is tugging at him, like a hook stuck in his consciousness. He doesn’t know what it is—usually when a memory tries to pull him back through time, or when something from the past leaks into the present, he can identify what triggered it. But this sensation is unfamiliar, and getting stronger. He grips the railing with one hand and steadies himself against the wall with the other. When he finally arrives at his door and stumbles into his apartment, Eli is exhausted. His limbs ache from the day of labour and he’s growing lightheaded from the strain of resisting the pull of this memory. Or whatever it is. He drops his jacket on the floor, leans against the kitchen counter with both hands, and allows his mind to drift toward this unknown force.

It pulls him inside fast. His legs tremble, and he’s swallowed before the fear of being swallowed can fully form. He realizes that it is a memory, but it’s not his: somehow, it’s Russell’s.

Muscles twitch, head swims, vision falters. He knows his heart is racing and there’s a pounding in his skull, but other than that, it’s hard for him to feel his body. He might be crying, but he doesn’t know what about. The room reeks of piss, smoke, and alcohol. Eli is on the floor but doesn’t remember collapsing. There are shadows moving in his peripheral vision, people he doesn’t recognize. They step around him. Thoughts bubble up half-formed: Where is? How much did he? Dying?

Eli hears a crash of something nearby, then slips out of consciousness completely.

The next morning, after Eli runs to the bathroom and throws up more than was in his stomach the day before, he calls in to Francesca’s Inn and tells them he’s sick. It’s not a lie, but his boss sounds suspicious. When he finishes the call, he looks at himself in the bathroom mirror. He looks as bad as he feels, and there’s a long blue bruise on his jaw. He carefully brushes his fingertips against the spot. He’s not sure if this is where he hit the floor or if this is a side effect of time travel.

Eli returns to the kitchen. His jacket is still lying where he dropped it last night. In the opposite corner of the room, he sees broken glass. He rips a paper towel off the roll and starts picking up the pieces. His hands are still a little shaky, and he makes a mental note to eat something soon.

The picture frame that fell off of the wall contains a photo of himself and Viola on vacation, standing in front of Niagara Falls. Her hair was its natural brown colour, long, and she was wearing big round sunglasses. He had been trying to grow a moustache at the time, unsuccessfully, and his plaid shirt had noticeable pit stains. The glass is destroyed and the frame has popped apart at one corner. Eli lifts the whole mess and dumps it into his trash can. He makes himself some toast and jam, eats it at the counter, then fishes the photo out of the trash and puts it in a drawer.

Eli finally takes off his boots and lies down on his bed. He’s still nauseous, and his head and body ache. He wonders if he should go to the hospital, but he doesn’t know what he would tell them. Maybe they wouldn’t find anything wrong with him at all.

He tries to think about when it started—losing time. Definitely before he met Viola, before Russell moved away, before graduation. Before that? Did it happen in elementary school? Eli didn’t think so, but then, he didn’t have a whole lot of past back then. Would it get worse as he got older? Would what happened last night—other people’s time pulling him in—would that happen more?

Eli suddenly feels something on the bed with him. The mattress creaks as she steps, slowly and carefully, toward his chest. He can’t see the apparition, only feel it—Wednesday’s paws kneading the blankets and then her weight settling on him. Her comforting presence gives him permission to close his eyes. The purring guides him to sleep.

Hi Mom,

Sorry, but I don’t think I’ll make it to visit today. I’m feeling pretty sick. Maybe picked up something at work. We still on for Saturday? E-mail me please?Love you,

Eli

Eli thinks about calling Russell all afternoon, but doesn’t know what he would say. He paces the apartment, practising out loud for a conversation that will never happen.

“Are you O.K., man? Hey, man, is everything O.K. with you? Listen, man, I’m here. Talk to me. You don’t have to—please don’t—don’t—” He presses his palm on the kitchen counter where he passed out the night before. His stomach churns. “Don’t go to New York. Don’t talk to Dylan. You deserve so much better than that, that asshole! Jesus Christ. You idiot. You asshole! You used to tell me everything. How? How did you do this?”

Eli’s voice cracks in his throat.

“How could you leave me? How could you leave me alone? Don’t disappear again, you asshole, you bullshit asshole, you’re so full of shit, fuck.” Eli punctuates the string of curses with a hurt noise like a scratchy growl.

His phone goes off in his pocket, and he feels his chest seize up as if he has been caught. He checks and sees his mother’s number. He takes a deep breath, wipes his face, and answers.

“Hi, Mom.”

“Hey there, honey,” she says. “You’re not feeling good either, huh?”

He forces a chuckle, rests on the futon. “Yeah, just a stomach bug for me, though.”

“Well, drink plenty of fluids. And you don’t have to drive up this weekend if you’re still not feeling well.”

“Mom, it’s Christmas,” he says dismissively. “And you’re all laid up. Of course I’m coming.”

“It’s not a big deal. I know it’s a drive—”

“It’s, like, two hours, Ma.”

“Well, I guess that’s true.”

Eli feels the cushion beneath him shift; a memory starting to rise around him. He tries to ignore it. He wishes, again, that she would reply to his e-mails instead of calling.

“So, uh, did you look at the pictures?”

“Which pictures?”

“Of the apartment?”

Silence.

“My apartment that I sent you? Yesterday?”

“Oh, right. No, I’m sorry, honey. I’ve been . . . you know.”

“Yeah, that’s O.K.,” Eli says. “I just want you to know, you know, that I’m completely serious. You can move in here. It would be a lot easier, you know, if anything happens—I’ll be right here.”

“I’ll be O.K.,” his mother insists. “I’m going home the day after tomorrow.”

“Well, what if, uh, you know,” he struggles to say the difficult thing without using any of the difficult words. “What if it’s something else next time? Like, if no one’s around and—who knows? You could move here, or—I don’t know, maybe I could move in with you.”

“Honey, I’m fine.”

The words pierce Eli’s calm and bring on the memory in full force—he cringes as he hears a yell, and then a door slamming. He sees her from far away, through a window in his childhood home. His mother is running from the house and down the street. Part of him stays at the window, calmly allowing the memory to unfold before him, while the frightened child he was runs outside after her. “Mama, mama, I’m coming too.” She turns, looking shaken for a split second, then forces a smile. She crouches down and tucks a strand of thin black hair behind her ear. “Honey, I’m fine,” she says. “I just thought I’d go for a walk to clear my head.”

Eli watches as the child puts on a cheerful face and pretends to believe her. He watches the child learn how to lie.

“O.K.,” Eli says. His mouth feels as if it is full of a thick, sticky syrup that tastes like dust. “We can talk about it later.”

Eli buys another tube of hand lotion before work the next day. When Russell gets into the car, Eli hands it over and tells him to keep it.

“Thanks,” Russell mumbles, pocketing it.

“Last day,” Eli says.

“Yeah. Y’think it’ll be slow?”

“Who knows,” Eli says. “Maybe there’ll be a bunch of people who waited until the last minute.”

“Shit, I hope not,” Russell says. “How’re you doing, dude? You look kinda beat up.”

“I’m fine,” Eli says.

“How’s your mom?”

“She’s fine,” Eli says. “Have you figured out what you’re doing next week?”

“Guess not,” Russell replies.

They find ways to avoid the topic for the rest of the day.

Hey Mom,

Just got off work and headed to bed. Let me know if I can pick anything up on my way over tomorrow. Merry Christmas!Love,

Eli

It’s after eleven on Christmas Eve when Eli pours himself a glass of bourbon and settles in to watch The Muppet Christmas Carol. The Ghost of Christmas Past had just taken Scrooge’s hand when Eli hears his buzzer going off. He hits Mute and gets up. The sudden visitor makes him nervous, even though he knows who it will be.

Eli buzzes him up and waits, leaning against the kitchen counter and swirling his drink, watching the ice cubes melt. There’s a knock, and Eli opens the door.

Russell is sweating despite the cold, wearing an oversized winter coat and backpack with ripping seams. He’s holding out the gloves he wore when they dragged Christmas trees.

“Hey, man,” Russell says. “I just wanted to return these.”

Eli did buy them, but hadn’t expected to get them back. They’re crusted in dirt and sap and Eli knows they’ll go into the garbage by tomorrow morning. He takes them.

“Thanks,” he says.

He waits for Russell to step inside. “Come on, man. Come in, have a drink.”

“Yeah, O.K..”

Russell takes a seat on the futon while Eli pours another glass. He grabs a chair and sits across from him. The Muppets are still on the TV, muted. Russell grimaces as he takes a sip. Bourbon isn’t his drink.

Something occurs to Eli.

“Did you walk here?”

“Yeah.”

Another sip, another grimace.

“My stepdad kicked me out again. On Christmas Eve. Can you believe it? New record for him on being an asshole.”

Eli stares into his drink.

“What are you going to do?”

“Well, he’ll let me back in tomorrow morning. That’s how he operates. But the job’s done and I’m sick of it, so.”

“So, what?”

Russell shrugs.

“Might leave.”

“Leave town?”

“Yeah.”

“Like, on a bus or something?”

“Yeah. Or I could hitchhike.”

Russell sees Eli’s skepticism and gives a short, sharp laugh.

“You know I’ve done it before.”

“Are you going to move back in with Dylan?” Eli says as evenly as possible.

Russell shrugs again, raps his knuckles on the arm of the futon.

“He’s dealing again. So. Nah, I don’t think so. And anyway, fuck him.”

Eli extends his glass, toasting the sentiment. Russell laughs again, more relaxed, and touches his glass to his friend’s.

“You deserve better,” Eli says.

“I guess.”

“You do.”

“Yeah, well.”

Russell takes a gulp, a hot, courage-gathering gulp.

“I have to figure something else out before I fucking kill myself.”

The air in the small room feels heavy with the statement and all it contains. Eli yearns to travel back in time—in a real way, a useful way. Back to when things were simple, or at least when things were difficult in a more familiar way. He realizes this is the moment one of them should suggest that Russell stay, stay right where he is.

Eli feels the familiar sensation of the world sliding away, but for once, time does not shake loose. Instead, it hardens: the moment crystallizes, and Eli can see every side of it. He rotates it in his mind, feeling every groove, all the possibility and regret it contains. Through the prism of this moment shine infinite pathways.

He can feel out the path if he extends the offer—the lost time gets much worse, then gets a little better. Russell is still angry and wounded, but safe. Eli feels resentment down this path, most of it his own. More than anything, Eli feels hurt. He feels Russell hurting him, and he feels himself hurting Russell. Lashing out at each other becomes the rhythm they live by. Eli feels pain, passed back and forth, over and over, until the path stretches too far for him to follow.

He grasps with his mind for another seam, one that traces the way of no invitation, and finds it—long, smooth, and calm. Russell goes back to New York. Eli visits his mother. He still experiences the past and present bleeding together. He manages. There are none of the sharp and hot feelings of hurt here, just uncertainty. And a low, dull throb of shame.

“You O.K., man?”

With a snap, the crystal shatters, and Eli is in the present. Russell is eyeing him, worried that he’s drifting again. Eli tries to look at his friend from another angle, but is left only with a hollow feeling. Though he’s never seen into the future before now, he finds it suddenly maddening to only be able to see this one Russell, locked in this one moment, and to not know what he will do.

“Yeah, I’m fine.”

Eli feels sick with himself, a feeling stuck to his bones and his guts, making it difficult to breathe and swallow. He can invite Russell to stay and see what kind of mean, petty, terrible friend he’ll turn out to be. Or he can take the easy path and keep his cowardice his own secret.

Eli finishes his drink and says nothing. The moment slips away.

Russell lies, says he’ll head back to his parents’ for the night. Eli pretends to believe him and gives him a hug. They promise to keep in better touch.

After he leaves, Eli returns to the TV. Scrooge has seen the error of his selfish ways. Eli doesn’t pay much attention—he’s seen this movie a hundred times, and he’s watching through the fog of the thought that he’ll never see his best friend again. When he had watched this story as a young girl, he believed implicitly that he’d grow up to be a good person. It seemed easy and obvious, being good.

Fifteen minutes and another glass of bourbon later, there’s a noise at the door. He tries to enter unannounced, but Eli had locked it, and the tension loosens in the moment it takes Eli to get there and fumble with it until it opens.

Russell stands in the doorway, his face sort of screwed up. He never left the hall. He’s struggling to ask the question, and of course he is—the question has to claw its way up into the doorway from the moment that had passed, the right moment. This moment isn’t right at all—the TV is still making cheerful noise in the other room. There are no tears, no heavy revelations, no promises, no embrace.

Eli lets him stay, all the same.