Trotsky moves apartments every year. Usually it’s because the credit agencies find him and want him to pay for his furniture. But sometimes it’s because he wants to live in other people’s homes.

He always keeps copies of his keys. He lets himself back into his old apartments months later. No one ever changes the locks. He wanders around the apartments, looking at how the new tenants have furnished them.

He sits on the couches and lies on the beds. He turns on the computers and goes through the files until he finds the hidden porn stashes. He makes himself something to eat and does the dishes.

He never sees any sign he’s ever lived in any of these places.

He goes back to one of his old apartments, over a convenience store, and finds it turned into an art gallery. Paintings line the walls where he had hung photos. The bedroom is a sound installation. The room is empty of everything besides several speakers on poles that play the sounds of different people breathing. He listens to each of them for a long time.

In some of the apartments, he takes photos from their frames and takes them home. He puts them in his own frames.

One day when Trotsky is in one of his old apartments, the new tenant comes home.

Trotsky is standing in the bathroom, brushing his teeth with her toothbrush, when he hears the lock turning. He steps into the bathtub and pulls the shower curtain closed as the door opens. He still has the toothbrush in his mouth.

He listens to her move around the apartment, opening and closing cupboards in the kitchen, making herself a cup of tea. The toothpaste is burning his mouth now, so he gets down on his hands and knees and spits it into the drain. When he gets back up, he doesn’t know what to do with the toothbrush. He sticks it in his pocket.

While he’s standing there, the woman comes into the bathroom. She sits on the toilet and pees. Trotsky holds his breath. She reaches into the tub and turns on the water, but she doesn’t pull back the curtain enough to see him.

Trotsky waits until she goes into the bedroom and then gets out of the tub. He dries his feet on the mat so he doesn’t leave tracks. She’s left the bathroom door open, and he peeks out. She’s getting undressed in the bedroom, her back to him. He goes down the hall, but instead of leaving, he steps into the kitchen. Her tea is still on the counter, and he takes a sip. He tastes her lipstick on the cup.

When she gets into the shower, Trotsky goes into her bedroom. She has the same Ikea bed as he does. He listens to her singing in the shower as he looks into her laundry basket at the clothes she was just wearing. He goes into her closet. He pushes past the hanging clothes, into the back. He sits down behind some boxes. He waits.

The woman comes out of the shower, wrapped in a towel. She drops the towel on the laundry basket and puts on pyjamas she pulls from the dresser. She goes into the kitchen and comes back with her tea and a magazine. She climbs into bed and reads, sipping from the tea every now and then.

Trotsky can taste the tea again. He smells her on the clothes in her closet. He wants to reach out and touch her.

When she turns out the light, he waits for what feels like an hour before he moves. Her breathing is deep and regular at this point. He moves out of the closet slowly, listening after each step. He stands beside the bed and listens to her breathe some more. He closes his eyes and tries to imagine what she’s dreaming.

He takes her toothbrush with him when he leaves.

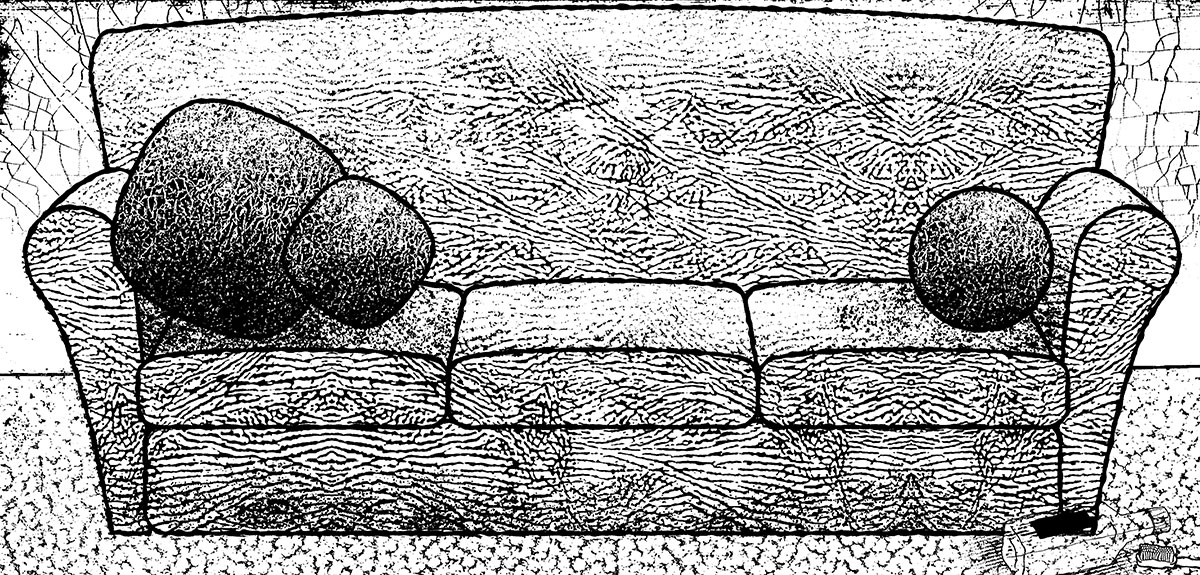

Trotsky lets himself into another one of his old apartments, and this time waits for the new tenant to come home. The closet is too small to hide in in this apartment, so he lies behind the couch instead. He’s not there long before he hears the door open and close.

“Hello? ” a man says.

For a moment Trotsky thinks the man knows he’s there. He wonders how. But the other man doesn’t say anything else. Instead, he goes into the kitchen and begins going through the cupboards.

Trotsky peeks around the corner of the couch and watches him. The other man wears a postal uniform. He has a postal bag slung off one shoulder. As Trotsky watches, he takes a bottle of Scotch from a cupboard and drops it in his bag, then an espresso maker from the counter.

When the other man goes into the bedroom, Trotsky gets up and follows him. He looks around the door frame and watches him empty the dresser drawers onto the floor, then drop a jewellery box into his bag.

When the mailman opens the closet door, Trotsky steps into the room.

“What do you think you’re doing? ” he asks.

The mailman spins around and stares at Trotsky.

“I didn’t think you were home,” he says.

“I’m not,” Trotsky says.

“I’ll put it all back,” the mailman says.

Trotsky watches the mailman as he puts the jewellery box back on the dresser, and picks up the clothes from the floor and shoves them back in their drawers.

“I don’t normally do this,” the mailman says.

“Neither do I,” Trotsky says.

He follows the mailman into the kitchen and watches him put the Scotch back in the cupboard and the espresso maker back on the counter. Then they just stand there. Trotsky’s not sure what to do next.

Then they hear the sound of a key in the lock.

They both dive behind the couch. The mailman has to lie on top of Trotsky for both of them to fit. Trotsky can smell the sweat on him, and he can barely breathe from his weight. The mailman shakes his head at Trotsky as the tenants walk in.

The tenants are a man and woman. They’re laughing about something, and then they stop. Trotsky thinks maybe they’ve seen some sign of him and the mailman. He tries to think up something to say.

It’s not what you think.

He’s the robber.

I was just here waiting for you.

Then he hears the sounds of the man and woman kissing.

He peeks around the corner of the couch and sees the man has the woman up against the hallway wall. He unbuttons her shirt and runs a hand over her breast. He drops his head to her other breast, and then the mailman drags Trotsky back behind the couch. He shakes his head at Trotsky again and draws a finger across his throat. Trotsky doesn’t know if the mailman is threatening him or trying to tell him what will happen to them if they’re caught.

The man and woman go down the hall, to the bedroom. Trotsky and the mailman stand up when they hear the bed start to knock against the wall and the woman cry out. The mailman goes back into the kitchen and puts the espresso maker in his bag again.

“What are you doing? ” Trotsky whispers, following him.

“I don’t know who you are,” the mailman whispers back, “but you’re not who I thought you were.”

“I get that a lot,” Trotsky says.

When the mailman goes to put the Scotch in his bag again, Trotsky lets himself out. He sits on the steps at the front of the building and calls the police on his cellphone. He wants to report the burglary, but when the operator answers, he can’t think of anything to say.