The Trailer

The worst thing about being dead is the pain. I felt like I was being crushed inside for months after the heart attack.

The kids tried to help ease it before Sarah, my wife—my ex-wife now, I guess—took them away with her. Samantha, my daughter, told me the pain meant my heart was broken. She said it would feel better if I came home again. Jesse, my son, said maybe being dead is like when you scrape your knee or elbow. You get a scab for a while, but then the pain goes away.

Sarah wouldn’t talk to me after I died. She wouldn’t even see me. She changed the locks on the doors after she kicked me out. I tried to come back to visit the kids, but she wouldn’t let me in. I had to talk to them through the door, or on the phone. Samantha said Sarah worried I’d give them whatever it was I had. But I didn’t have anything.

My doctor said everyone dead feels the pain. He said there are different theories about it. The people who think our condition is caused by all the preservatives in our food say it’s a chemical by-product. The religious people think it’s purgatory, that we’ll be able to die for good once we’ve suffered enough. The medical experts think it’s the body’s memory hanging on to the last seconds of life. My doctor said if I think feeling my heart attack all the time is bad, I should try to imagine what burn victims feel.

I just wanted it to stop.

The Willy Lowman

The second-worst thing about being dead is you have to keep working. I still had my share of the mortgage payments, even though I didn’t live in the house any more. And now I also had to pay rent on a new apartment. I had to buy gas for the car. I didn’t have to eat any more, but I kept the fridge and cupboards stocked with groceries in case Sarah ever let the kids come and stay with me.

All the bills meant I had to keep on with the life I had, despite being dead. There were some physical changes, obviously, like not being able to sleep at night. But I went to the office with everyone else in the morning. I went to the food court with my co-workers for lunch and watched them order the same meals I used to order and eat. I looked at the images on the video menus, of the men in suits with hamburgers, the children with fish sticks and fries, the women with salads, but I couldn’t make myself hungry. I went to the bar after work with my co-workers and ordered drinks I didn’t drink. I did everything but play minigolf with them.

That’s because I had my heart attack on the seventh hole of Maximum Mini Golf in the Evergreen Mall during a game with two of my co-workers, Dylan and Hakim. I was ahead for the first time ever against those two. I was leaning on my club, watching Hakim tap a putt into the Wheel of Vegas, when suddenly I couldn’t breathe. I knew he was aiming for the free massage at House of Pleasure, but he hit the free gym pass at House of Pain instead. That’s when everything froze inside me and I fell to the fake turf.

I have to give Dylan and Hakim credit—they did what they could for me. Dylan performed his best impression of the C.P.R. he’d seen in the movies, while Hakim called 911 before taking photos of the scene with his phone. One of those photos—me with my tongue sticking out and my shirt torn open as the paramedics worked on me—went around the office mail afterward. I forced a laugh and a shrug when I saw it on people’s computers and tried not to think about what was happening to me in that photo. But I couldn’t forget staring up at the monitor as I lay there, unable to move, unable to do anything but watch the different images it flashed: a flag waving in the wind, a set of Nike minigolf clubs and balls, a smiling woman who promised to make me a millionaire off my accident lawsuit. When the paramedics rolled me away on the stretcher, the monitor showed a beach on a tropical island somewhere, with the caption, “YOUR AD COULD BE HERE.”

The paramedics did their best to save me too, but I was already gone by the time they arrived. That’s what the driver told me later in the hospital after the emergency-room doctor pronounced me officially dead. “Tough break,” the doctor said, putting away the paddles he’d been shocking me with and handing me a release form to sign.

“Are you sure? ” I asked him. “Can I get a second opinion? ”

He looked at the paramedics. The driver nodded and said, “Dead.” The other one was playing a game on his cellphone and didn’t even look up.

I signed the release—it took several attempts because I still wasn’t used to the numbness that comes with being dead. But sometimes now I wonder what would have happened if I hadn’t signed it—if I wasn’t officially dead.

Anyway, the paramedics drove me home in their ambulance. I lay on the stretcher in the back. There was no room for me to sit anywhere. The driver said this situation was turning into a real epidemic. He offered to take me to Maximum so I could finish the game with Hakim and Dylan, but I said no, they were probably too far ahead of me now to catch up. Then he offered to tell my wife so I wouldn’t have to, but I said no to that too. I said there were some things a man had to do himself.

In all honesty, I was planning on keeping it from Sarah, but she knew from the moment I walked in the door. She looked up at me from her yoga mat in front of the TV and then leaped to her feet and ran screaming for the bedroom, where she locked herself in.

I knocked and knocked on the door, but she wouldn’t let me in. “Go away,” she cried. “I’m in mourning!”

I went back to the living room and watched the yoga program. A man was twisted into an impossible position. “Just hold it,” he said. “Keep holding it.” Sarah threw all my clothes out the bedroom window and then called me on my phone to tell me to get out. I was glad we’d sent the kids to urban survival camp for the week. But I didn’t know at the time I’d never see them again.

“I’ll sleep on the couch for a while,” I told Sarah. “Until you get used to the new me.”

“Until death do us part,” she said and hung up.

I went out and picked up my clothes. My neighbors were having a barbecue and everyone stood there with drinks and hamburgers in hand, watching me gather my shirts and ties, but no one said anything.

I called a taxi and waited in the front driveway. All the houses on the street looked the same. It was one of those cookie-cutter neighbourhoods. When we’d first moved here, I’d gone home to the place across the street by accident and didn’t realize it until I was at the front door. The house was for sale now. I wondered if having a dead neighbour was bad for property values.

I took the taxi to my car in the Evergreen Mall’s parking garage. I sat there for most of the night because I couldn’t sleep. I thought at first it was because of the shock of being dead and what had happened with Sarah. And trying to figure out how to explain it to the kids when they got home. I didn’t know back then that I’d never be able to sleep again. That’s why you see so many people like me working the night shift at convenience stores.

Eventually a security guard driving around the garage stopped and shone his flashlight on me without getting out of his car. He told me I had to move on. There was a lineup of cars at the exit. Each one had a lone man inside. I drove to the office and got to work paying my bills. And that’s been my life ever since.

The Hollywood

Not long after I died, I got promoted.

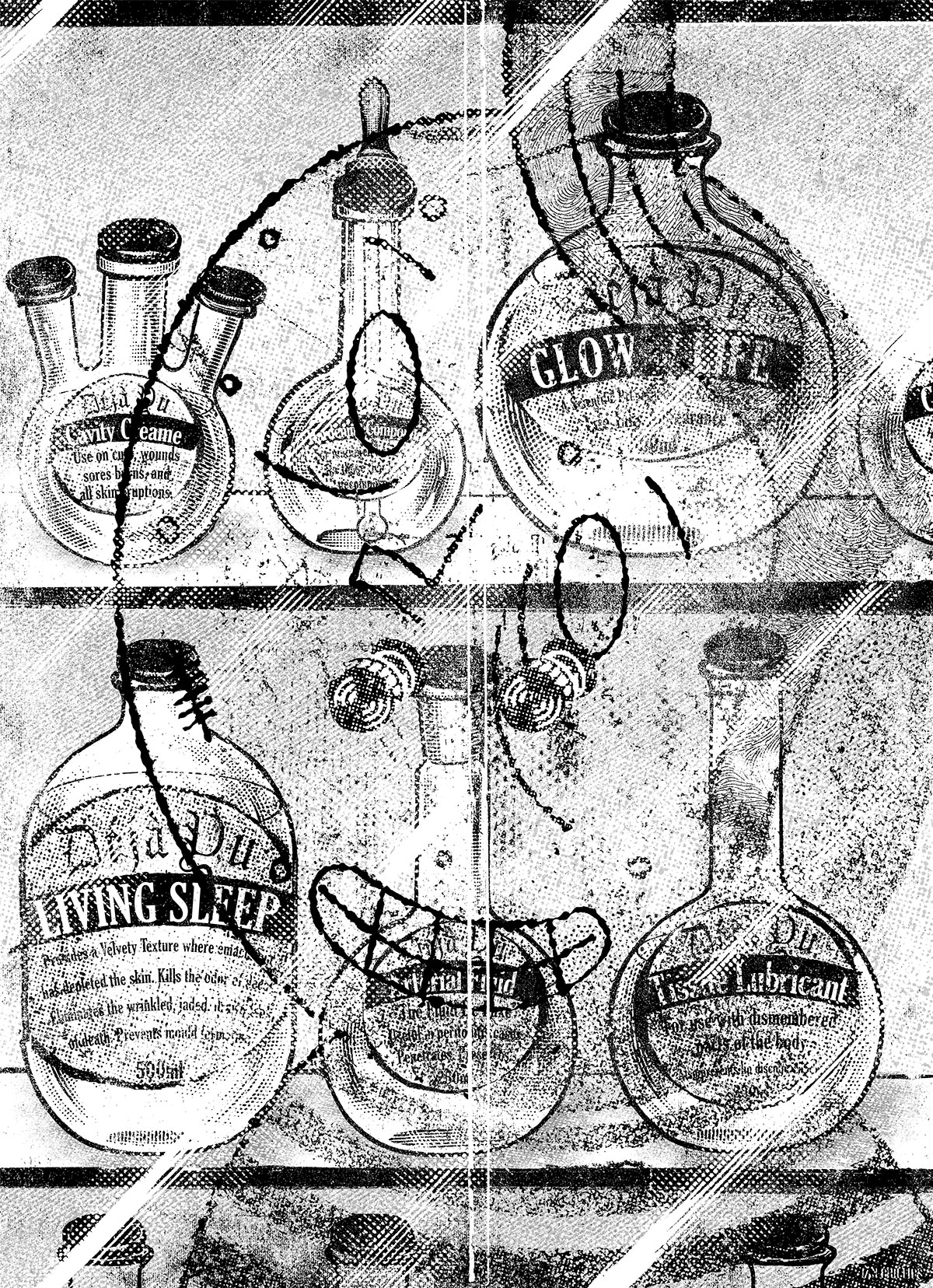

In fact, I got promoted because I was dead. I was put in charge of the Déjà Yu beauty products account. The next-worst thing about being dead is people can tell we’re dead. We have the tint to our skin, the smell, the stillness when we’re thinking about what’s happened to us. The Déjà Yu beauty products are supposed to make us look alive again. Creams to put colour back in our skin. Aftershave and perfume to mask the smell. Balms to make our lips look warm. Eye drops to sting our eyes and remind us to blink. Shock pads for our chests to remind us to breathe.

Like all other beauty products, they don’t really work. My team’s job was to make people think they do.

Before I died, I was junior member of the development team, which mainly meant I made runs to Starbucks for coffee and to Kinko’s for the mock-ups of the ads. But the E-mail the partners sent around the office a few weeks after my death said I was now in charge of the team because of my unique circumstances. I was the only dead person in the office, the E-mail said. Congratulations.

My co-workers all sent me their own E-mails saying I looked good. They said they could barely tell the difference from when I was alive.

I could tell from the looks that Dylan and Hakim gave each other over the cubicle walls they wished they’d tried harder to save me.

I didn’t really want to be in charge of the Déjà Yu account. I didn’t really know what I was doing.

The day of my promotion, I rearranged my monitor in my cubicle so no one could see the screen. I opened one of the company’s Screenplay for Success™ templates and studied its rules:

- The Trailer. Set the scene.

- The Willy Loman. Make the audience identify.

- The Hollywood. Give the audience some drama to keep them entertained.

- The Pitch. The product.

- The Punchline. Leave the audience happy and willing to buy.

There were large spaces left between each rule where I was supposed to add my notes. I couldn’t think of anything to fill the spaces. I closed the file and logged on to my home site instead. I watched videos of me and Sarah and the kids at the local Disney Time. I wanted to cry at the shot of Jesse and Samantha holding hands with the Goofy in the army uniform, but my tear ducts didn’t work any more. I phoned the house again to talk to the kids, but there was no answer. I tried to leave a message, but the voice mail was full.

The day after I was promoted, Hakim wandered over and asked if we were going to have a meeting about the Déjà Yu account. He said everyone had run out of spam to read.

I told the office manager I had to hold a meeting and she put us in the Coke room, which is a sign of how seriously the partners took the Déjà Yu account. I’d only been allowed in the Pepsi room before. The Pepsi room is just a standard meeting space with Ikea chairs and a table, but the Coke room has Aeron chairs and a video screen.

My team consisted of three people: Hakim, Dylan, and Phoenix, an intern from the university marketing program. I wasn’t sure if Phoenix was her real name or not. When I sat beside her, she pushed her chair to the side, away from me. We all stared at the blank video screen for a while. It took me a moment to realize they were waiting for me to say something.

“Does anyone have any ideas? ” I asked.

No one said anything. They all looked from the screen to me. I looked back at the screen. The only thing I could think of was my family at the Disney Time. “Home video,” I said. “We’re going to make a home video.”

They kept looking at me.

“We’ll show them what they want,” I said. “Life like it used to be.”

I put Dylan in charge of finding us a set, Hakim of putting together a film crew from our regulars. Phoenix said she could get actors for free from the university’s drama program.

“We need older people,” I told her. “People with kids.”

“Half the people in university now are older than you,” she said. “The place is full of people who’ve lost their jobs to zombies.”

I said that would be fine but let’s not use the word “zombie.” I went back to my cubicle and called home again. Still no answer. The voice mail was still full.

Dylan found us a house to shoot in a few days later. It was in a subdivision on the outer edge of the city. River Spring or River Canyon or River Valley or something like that. It was an area of scrubland, near an incineration plant. I didn’t see a river anywhere.

The house had a mortgage foreclosure notice on the door, but there was still furniture inside. It was nicer than the furniture in my old house.

“Why didn’t they take all this stuff? ” I asked. “They could have got this out before the locks were changed.”

“The bank guy told me they owed money on everything inside the house too,” Dylan said.

“I still would have taken it,” I said.

The director and cameraman Hakim hired both wore T-shirts with the Soviet Union’s hammer and sickle on them. They stood outside the house and talked about how many African families would fit inside it while they smoked hand-rolled cigarettes. When I went out to say hello to them, they just stared at me and didn’t answer.

I went back inside and found Hakim. He was in the kitchen going through the cupboards, inspecting the glasses and plates.

“Where did you find these guys? ” I asked him.

“We couldn’t go with the usual union guys,” Hakim said. “On account of you.”

“What’s wrong with me? ” I asked.

“Union crews can’t work with zombies,” Hakim said. “They’ve got concerns about outsourcing and seniority.”

“Can we not use that word? ” I said.

Hakim shrugged and dropped some glass tumblers into his shoulder bag.

I looked out the window at our film guys again. They were unloading gear from their van now. “But communists are O.K. working with me? ”

“I didn’t say that,” Hakim said and walked away.

The real problem was the actors.

When Phoenix drove up with them, I could see they were dead. All of them—the man, the woman, even their little girl. They stood outside, a little apart from each other, and stared at the house without blinking.

I pulled Phoenix aside, around the corner of the house. “What is this? ” I asked her. “I thought you were getting me students.”

“They are students,” she said. “They came back to school after they died and lost their jobs. Except the girl. She still has a job.”

I peeked around the corner, at the girl. She was brushing the hair of a doll.

“She’s been dead for decades,” Phoenix told me. “She was one of the first, back before anyone knew it was happening. She’s actually a drama prof at the university. Revelatory hiring practices.”

I went back inside. Hakim was unpacking the kit of Déjà Yu samples for the actors. I took some of the cream from his kit and put it on my arms and face. Hakim watched me but didn’t say anything.

The director came over and asked me what the plan was for the shoot. “Just make them look normal,” I said.

“What do you mean, normal? ” he asked.

“Make them look like a real family,” I said.

I went into the bathroom and studied myself in the mirror while the actors put on the Déjà Yu stuff. The cream made me look slightly more alive again, but I didn’t feel any different.

The director decided to do a breakfast scene. I sat on the couch and watched them shoot it in the kitchen. The director told the little girl to ask her parents for a new phone. He told the woman to say she was getting plastic surgery done again. He added she should look like she was on anti-depressants. He told the man to think about the money he was going to take from Third World countries when he went to work.

“So it’s just like before I died,” the man said.

“Exactly,” the director said. “Act it like it’s the morning of your death.” I closed my eyes while they shot the scene.

When they were done, I told the crew to come back the next day. I told the actors we wouldn’t need them any more.

“No offense,” I said, “but the last thing dead people want to see in an ad is more dead people.”

“I was thinking the same thing myself,” the man said.

“Maybe plastic surgery is the way to go,” the woman said.

The girl didn’t say anything, just kept brushing the hair of her doll.

I pulled Phoenix into the bathroom and told her to come back the next day with living actors. She sighed, but agreed. I went back to my apartment and tried to call home again. The voice mail was still full. I watched cop shows all night long. They were all the same. A man took his family hostage, the police surrounded the place and sent in the dead cops, maybe even some dead dogs. The cops got shot but it didn’t matter. Sometimes they brought everyone out alive.

Sometimes they killed the hostage-taker and brought him out screaming that he was going to sue them for the bullet holes in his chest or head or both. In one show, the cops killed everyone in the house. It was a drug lab, and they shot the wrong bottle of something and the place blew up. The cops and the newly dead family all staggered out different doors, but then the man and his wife and son all found each other in the front yard and hugged, their skin still smoking from the fire.

And that’s when I came up with the idea to get my family back.

The Pitch

The next day, Phoenix showed up with a real-life family. Not only were they alive, but they were actually a family. A man, a woman, and their son. I could tell they were together by the way they sat on the couch, leaning against each other without saying anything while they waited for the cameraman and director to set up for the shot again. It was just like how I used to watch movies with Sarah and the kids.

“Where did you find them? ” I asked Phoenix.

“They’re mine,” she said.

“You don’t know how lucky you are,” I said, but she just shook her head.

The director gave the same set of instructions to Phoenix’s family as he had to the dead actors, even the comment about taking money from Third World countries.

“I thought communism was dead,” I said.

“So are you,” the director said, “and yet here you are.”

Hakim didn’t bother putting any of the Déjà Yu cream on the actors, seeing as they were already alive. I put some on my face and hands again while they tested the lights for the scene. I thought maybe it would work eventually if I just kept applying it. Hakim watched me but didn’t say anything.

By the time they started shooting the scene, my skin was burning. When they reached the part where the son asked for a new phone, I felt like I was on fire. I ran for the bathroom to wash off the cream, but the taps in the house didn’t work anymore, so I rubbed it away with a towel instead.

When I looked in the mirror, my skin was pitted and eaten away where the cream had been. I went back out into the kitchen. Everyone stared at me. Hakim couldn’t conceal a small smile. Phoenix and her family all put their hands to their mouths, even the boy.

I couldn’t stand them seeing me like that, so I left.

I went home. My home where my family lived, not my apartment. I rang the doorbell, then knocked when no one answered. Then I kicked in the door. I waved at my neighbours, who watched from their windows, and went inside. I was going to kill my family. I was going to do it as gently as I could, so they wouldn’t hurt later. Maybe pillows over their faces or carbon monoxide in the garage. Then they would understand. Then they would be like me. Everything would go back to the way it was.

But no one was home.

And no one would ever be home again.

The place was empty, all the furniture gone, everything. Just some outlines in the carpet upstairs where the beds and dressers had been. Not even a note left to say where they’d gone.

My phone rang. It was the executive assistant for the partners. They wanted to know where I was.

“I don’t know,” I told her.

She said they’d heard about what happened. They wanted to know the status of the Déjà Yu account.

I went to the bathroom and looked at myself in the mirror while she talked. There were still spots of cream on my forehead and neck. My skin was still burning, and strips were peeling off now, hanging from my face. The skin underneath looked raw, but grey instead of red.

I understood everything then.

I was dead.

“Are you there? ” the executive assistant asked me.

“Yes,” I said and disconnected.

I went back to Maximum Mini Golf in Evergreen Mall. I bought a pass and took a club and a red ball and started at the first hole like everyone else. I played through to the seventh hole. I waited my turn behind the other players and I recorded my score on my little scorecard like everyone else. When I reached the seventh hole, I lay down on the grass and looked up at the monitor. It showed a hamburger patty sizzling over open flames and then the flag.

Two men had just finished the seventh hole and were recording their scores. When they saw me on the ground, they took a few steps toward me and then stopped.

“Are you…? ” one asked, while the other took out his phone.

The hamburger was replaced by an attack helicopter blowing up a car in a desert somewhere. Men in suits and ties stood in the desert and cheered.

I didn’t hurt any more. My skin didn’t hurt from the cream, my chest didn’t hurt from the heart attack.

I didn’t feel a thing.

I was dead.

The Punchline

The monitor shows the “your ad could be here” tropical island again. I close my eyes and imagine the videos of me and Sarah and the kids at Disney Time again.

I imagine a motto superimposed on the videos of my family. The videos of my life.

“DÉJÀ YU MAKES THE PAIN GO AWAY.”

I imagine the ad playing on the phone of the man standing over me now. Playing on my computer at work. Playing before movies. Playing on monitors in restaurants and stores in malls everywhere.

I imagine the ad is so successful it gets me an actual office at the agency, with my name on the door. My name added to the partner list. My name on every business card and company E-mail.

I imagine I’m lying on the floor of my empty house.

I imagine the rest of my life.