Every other Saturday morning I slammed my face into Dad’s hard belly. He had no choice but to envelop me in a dewy, Irish Spring–smelling hug, even though bodily contact was anathema to him—a foreign phenomena, American in all the very worst ways.

He had the gruff voice of a lonely, heavy smoker—six hundred cigarettes and not much else for company all week—and he wore his blue suit, which was soft with wear because he never wore anything else. The rest of his clothes were in the closet upstairs.

He took me to a greasy spoon, where he ordered bacon with two runny eggs and home fries and I had a vanilla milkshake. He always gave me a quarter for the jukebox, which I clutched in my palm as I laboured over my choice before finally pressing G-something, but it was never the tune I intended. I would slink back into the booth in humiliation and Dad would say, “That’s an oldie—an oldie but a goodie,” and I would feel ever-so-slightly redeemed.

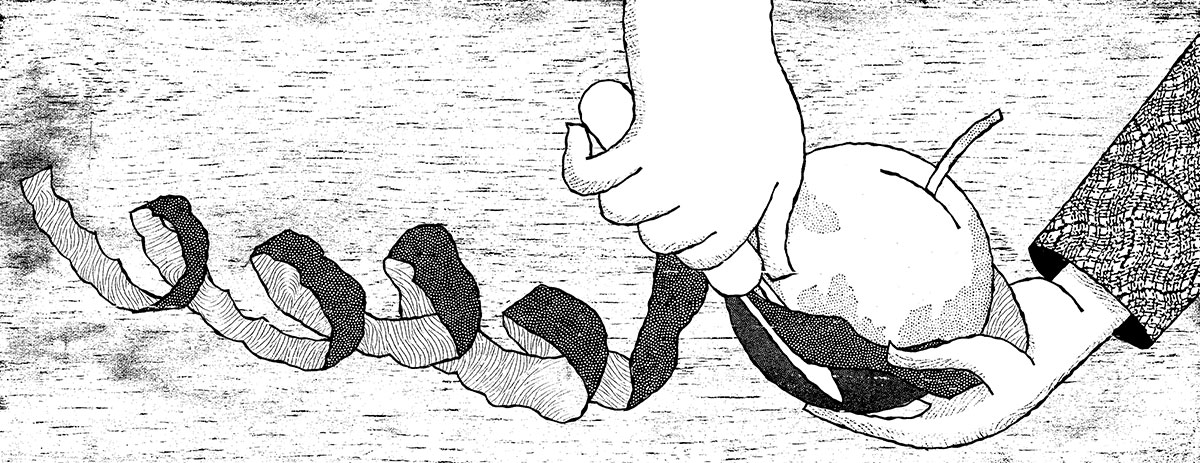

We spent the day at his office, where he did paperwork in the front room and I built a fort between boxes of paper and broken chairs. Later, he peeled an apple for me in one single strip with his Swiss Army knife. The traffic light cast alternating rays of red and green over the room as the sun disappeared behind the big buildings in the distance.

“Best be getting you home,” Dad said, and I obediently picked up my pencil crayons and put them into my satchel. We drove home in silence in the car with a pine air freshener hanging from the mirror and I wondered where Dad slept.

Mum never asked more than, “O.K.? ” when I got home. It was the year that everyone stopped speaking.

One Saturday I lunged into Dad’s stomach and opened my eyes to see grey. I pulled back in confusion—he was wearing a different suit. I wondered if Mum had let him upstairs. He had his bacon and eggs and I had my milkshake, and I pressed the jukebox button and for the first time ever I got the song I intended, and Dad said, “Don’t know that one,” and I worried I’d disappointed him.

When I came home that night Mum said more than, “O.K.” She said, “My friend Bill’s coming for dinner, so why don’t you change into your new dress? ” She had on blue eyeshadow and a skirt I’d never seen before. My new dress was laid out on the bed. I tugged it roughly over my head without undoing the zipper. I heard it tear before I felt it tear. I tugged some more.

“It’s broken,” I said standing at the top of the stairs, holding up my arms.

“Oh dear,” Mum muttered, wiping her hands on an apron. “Well, I don’t have time to fix it now.”

So I kept my arms at my side when I met Bill, refusing to shake his outstretched hand.

Mum served fancy food—coquilles St. Jacques—and I wondered what beach had shells so big, and whether we would ever have a holiday there.

“Delicious,” said Bill.

“Where does Dad sleep? ” I asked my mother.

Bill looked into his shell and Mum cleared her throat and said, “Not now, Ruby,” and took a sip of wine from Bill’s glass. Her lipstick left an oily pink mark.

I picked up my sticky shell and cupped it over my ear, relieved by the hollow roar of the ocean. Cream slid down my neck as I struggled to hear the echoes of speech within the abyss.