Zev’s back on Golden Avenue. Temporarily, he’ll tell you. He skulks along it in his scarecrow lurch, nodding to the neighbours as he goes. So far no one’s asked after his green Saab, and old Mrs. Boccia across the street even praised him for returning to look after his mother. Zev figures that’s the best possible spin he can put on his situation. And if anyone asks, he’ll say the Saab is in for repairs.

Golden Avenue ends in a garbage-strewn lot that separates the narrow Edwardian houses from the railway line in the west end of Toronto. The Zevbrowski residence is the last house but one, shaded by maples in springtime bud. From the window of his boyhood bedroom, Zev can see the worn footpaths of the baseball diamond and the lilac bushes behind which Betty Leung once treated him to some breathless kisses. On the wall above the bed his mother has replaced the crucifix he removed when he was thirteen. Zev leaves it up. He’s just a guest now.

The night before, the most shameful of his life, Zev had met his cousins Stan and Yannick in a borrowed van for a late-night dodge from his Yorkville condo. It was after midnight when he peeled off his black suit and climbed into bed while his mother snored down the hall. First his father, then his business, his car, and now everyone will know the condo has been rented out.

Just as he’d finally drifted off, the first Go train, rumbling in from the suburbs, shook the house at 6:09 A.M. When they started passing in half-hour intervals, Zev got up to face the day. In the living room he piled his furniture over his mother’s faded sofa and set up his desk. There were messages on his cell: inquiries after submissions, copy editors looking for work. Nobody called with good news any more. Then it was out the door to the office on Spadina Avenue he’d chosen to keep over his condo. Bedlam Books was nothing without its Chinatown perch.

Out on Golden Avenue, Zev ducked as Mrs. Leung, Betty’s mom, waved from her porch. Half a day and his cover was blown. There’d never been any privacy here. That’s when he knew he was back. Stuck. Trapped. Damned. Zev’s back.

Within a few days his mother was calling him Winicjusz again. Zev came home to plates of corned beef and cabbage drying out under tinfoil in the oven. He’d long ago stopped reminding her he didn’t eat meat, or that no one ate cabbage any more.

They never mentioned his father, or how he was found, crumpled by a stroke on a winter night, in his taxi, outside Shorty’s Variety, down the street. The neighbours all thought the old man had dozed off reading the paper again. Further indignity awaited Vinicus, Sr., at St. Joe’s, where he lingered two months, surrounded by machines that hissed and printed reports. Zev had sat by the bed wishing he had the strength to pull the plug.

In those two months Bedlam Books all but collapsed. Zev missed the London Book Fair and was late in organizing his spring launch. Wicked Sunday, his marquee novel, deservedly received brutal reviews. Worse, it had been the best of a mediocre lot. Even then he was struggling to find something unique to publish.

He also learned that Jaroszlaw Szonyi, the Warsaw poet since Solidarity, had signed the North American rights of his anthology over to Zev’s rival, in Brooklyn. He could hear his father cursing from beyond. Then his grant applications were denied—something about a lack of diversity. Bedlam Books would have to survive on the pittance it generated in sales. Impossible. It was around this time Zev knew he had to give up his condo.

On the rainy March morning of his father’s funeral, Zev slipped on the steps of St. Casimir’s as he and his cousins unloaded the casket. Thankfully, Father Bajor had been there to catch Zev under the arm. As he lay awake each night, Zev wondered if it would have been better if he’d dropped the casket and spilled his father onto the sidewalk. The accident prevented by the priest might only have postponed more doom.

Now he spent his evenings pouring over manuscripts in his mother’s living room. Among the lace doilies and the portraits of John Paul II and Lech Walesa, he quickly lost interest in stories of farmers fleeing their ho-hum Prairie hometowns, or of political intrigue in Ottawa. The poetry was also dull. Spring-cleaning metaphors. Flower cycles for victims of American imperialism. None of it had what Bedlam needed.

But where to find it? Most of his friends who still wrote had moved on to bigger publishing houses. Others had given up. His ex-girlfriend, the novelist Sarah Willey, now had a marriage to a lawyer and two little girls to manage. The poet Mark Purcel had become the gaming correspondent at a daily newspaper. Zev feared that the good days were over.

One morning in June he woke to find grey in his goatee. His brown hair lay like straw over his shoulders. His face sagged. Three years ago, Katie Shue’s The Redhead was in its third edition and he couldn’t work enough hours. Now he dragged himself downtown to the office every day.

His last remaining employee, Bonnie Hutchins, was making notes in a manuscript as he entered the office. Zev didn’t dare reproach her, since she’d scarcely spoken to him since he downsized her last month. Once an editorial assistant, Bonnie was a heavy blond woman of about thirty who called him Vincent, or sometimes Vince. He let her, too, because until his troubles started, they’d been getting along so well he’d considered asking her out.

One of the things he and Bonnie hadn’t talked about was how last week the leasing company had taken away the photocopier and the fax machine. Zev settled at his desk in the inner office and opened his laptop between leaning towers of manuscripts and takeout coffee cups. Stacked nearby were boxes of print overruns: the hockey stars’ cookbook, the anthology of nineteenth-century railway poems.

Now he had more worry. His father, who’d evidently spent too many afternoons at Woodbine Racetrack, had left the house heavily mortgaged. Unless Zev generated some income soon, his mother, who wouldn’t receive her pension for another two years, would have to sell it.

Determined to make Bedlam famous and slightly more solvent again, Zev wiped his round glasses on his shirttail and picked up the first manuscript at hand. The Dollhouse Songs was a series of linked sonnets about the pain involved in committing a parent to a chronic care facility. A hot topic, apparently, among aging boomers, but certainly not any fun.

Entropy Man, another story about a superhero, was more a screenplay treatment than a novel. According to the cover letter, the film rights had already been sold. The author, a daytime television anchor who reminded Zev that he’d had him on his show, hoped for a quick response. Zev tossed the whole package into his overflowing recycling bin. Fast enough?

Fishing for Birds was an ornithological treatise and not the steamy memoir of swinging sixties Soho he’d been hoping for. The Birch Switch detailed cruelties meted out during a rural Ohio boyhood. It wasn’t sexy either. Zev then endured the first ten pages of Rhododendron, an Indian doorstop, unsure if it was fiction or not. He dropped his head to the desk.

There was pressing correspondence from translators seeking payment and agents pitching new writers. There were letters from his lawyer, his landlord, and his landlord’s lawyer. Even his father’s lawyer, which was interesting. Authors accused him of withholding royalties, others of having lost their manuscripts.

Zev flung the letters and faxes into the air and watched them land on the hardwood floor. Problem solved. Bonnie, alarmed, opened the door to his office. Zev smiled at her, and wondered if she was the source of the rumours about his impending demise.

Yet it was his own wavering focus that was to blame. He’d followed up badly chosen books with shoddy marketing plans. To simplify matters, Bedlam was getting out of the translating business, effective immediately. Old Vinicus, descended from centuries of clever peasants, would hopefully understand.

In the kids he passed along Queen Street at lunch he recognized the new readers he needed to reach. Zev spent the next two hours at Pages and Chapters observing that people couldn’t get enough of superheroes, sex still sold, and graphic novels were hot. Women liked stories about shopping. Men always liked war. He also found an ad for a magazine launch that evening. There it was: fresh talent just waiting to be found.

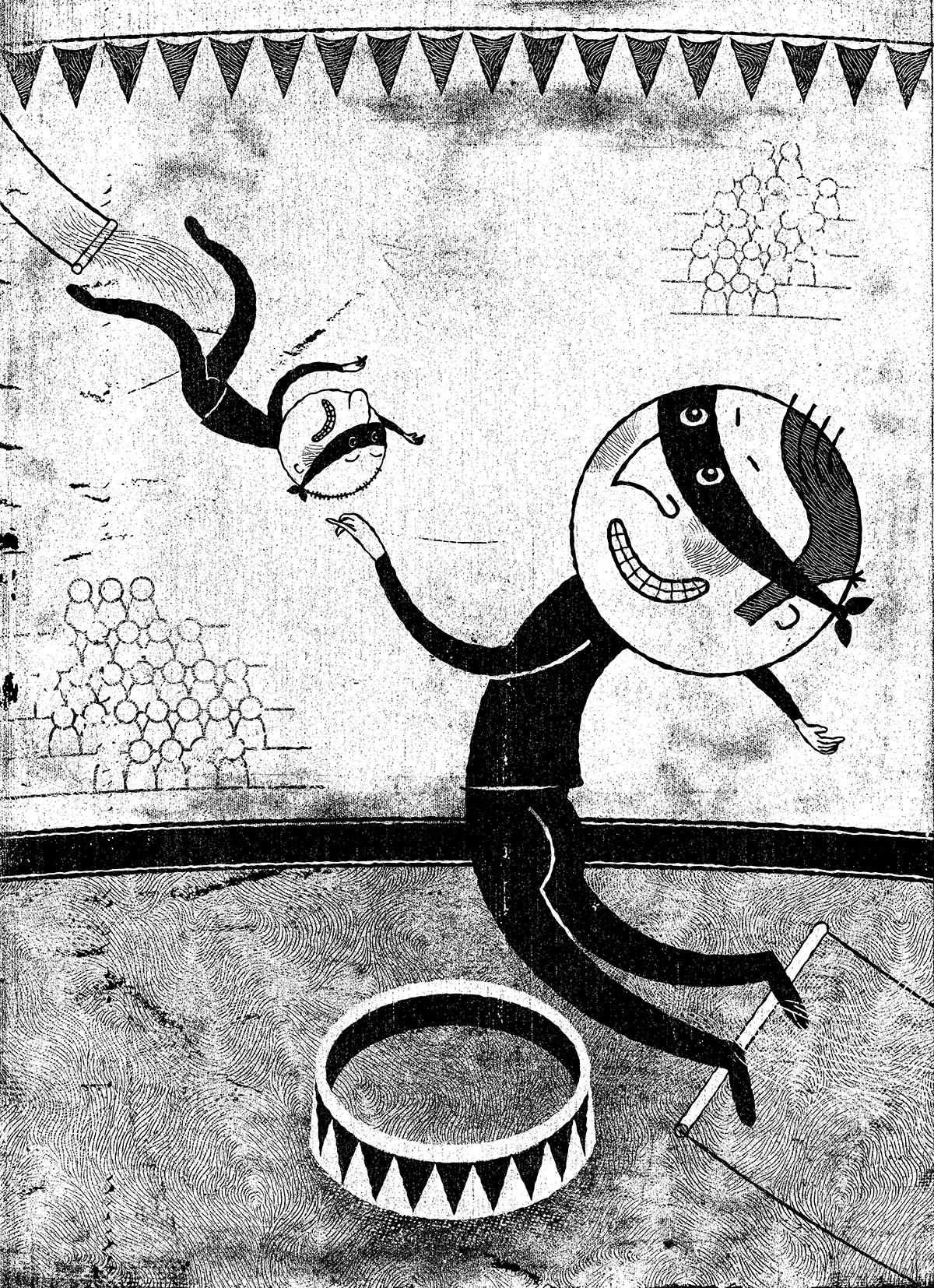

The office had been tidied when he returned to it. He really had to find some money to pay poor Bonnie. He read a manuscript about a group of anarchists staging a sci-fi musical, The Trapeze Thieves, that needed more of a story. But it had the bizarre edginess of a classic Bedlam book, and he packed it away to read on the streetcar.

The launch was at the Dolphin, in the Annex. Zev sat with his ginger ale at a wobbly cocktail table. Mudflaps, a complimentary copy of which he’d received at the door, contained glossy fashion and skateboard ads but very little text. The room filled slowly, most people avoiding the long, ponytailed man at least ten years their senior in the black suit and raincoat. Zev appreciated the respectful distance.

A man in a toque took the mic and announced that audience participation was encouraged. Zev yawned loudly; he’d barely slept since moving home. A fellow with a head of curly hair, whom Zev thought looked familiar, sat staring at him from the opposite side of the room.

First up was a slide show of a Barbie doll, in different outfits, provocatively posed in front of various fast-food outlets. A skinny kid with sideburns and an American accent announced the name and location of each restaurant and what he’d had to eat there. The Steak ’n Shake in Muncie, Indiana: double burger, large Coke. Or the Burger Barn, in Joplin, Missouri: catfish on a bun and a sweet tea. The slides were accompanied by a light show that uncomfortably reminded Zev of Laser Floyd at the planetarium.

He searched for the message in what he was seeing. Fatty foods and skinny dolls, legs like French fries. Maybe. It was probably important somehow that Barbie’s tour ended in California.

Loud music started and people flitted between tables. Apparently readings no longer occurred at magazine launches, and no one had a book for him. Too bad: it wasn’t often that publishers went scouting. Rising with a minor flourish, he positioned his fedora and felt the eyes of the crowd follow him out. Leave them talking.

At home, his mother was asleep on the couch again. Zev turned off the television before removing her glasses and settling the afghan around her. Every night her loneliness was as plain as his inability to comfort her. In the darkened kitchen he carefully ate whatever crusted mashed potatoes and creamed corn hadn’t been corrupted by the dried-out sausages. Then it was back to the manuscripts.

The following week he took the streetcar to Yvan DeSoto’s launch at the Parkdale Arms. Zev had read Yvan’s poems a year ago but hadn’t thought they were ready. Apparently someone at Cathedral did. The other two writers reading that night were unknown to him and, hopefully, unsigned. He had begun to suspect that Bonnie was funneling the better material to one of his rivals. Cathedral, for example.

As he took his seat he spotted the curly haired fellow from the week before. A woman read poems about an army of robot Amazons pillaging the training camp of the Arizona Cardinals, then a man old enough to know better read a clumsy story about the masturbatory habits of a teenager, presumably himself, obsessed with Lisa Bonet, from The Cosby Show.

Disgusted and bored, Zev fled. So too did the curly haired fellow, who followed him to the streetcar stop. Zev spun to confront him. “Is there something I can help you with? ”

The guy skidded to a stop. “You can give my book back if you won’t publish it.” Zev knew his own face revealed he’d drawn a blank. To compensate, he whipped out his notebook. “What’s your name? ”

“Derek Weiner.”

“My secretary makes note of every manuscript we receive. It’s not the only copy, right? ”

“No, but—,” Weiner started.

“So there’s not a problem, is there? We’ll get it back to you, Mr. Weiner. Good night.”

Zev had been stalked before, notably by an older woman writer of gory Stephen King imitations with whom he’d been briefly involved. He raised his arm for a taxi. The sooner he put some distance between himself and this man, the better.

But Bonnie hadn’t heard of Weiner. Zev and his assistant were talking again, perhaps because of the cheque he’d written her from what was left in his personal account. Over lunch at Peter Pan he’d learned that Bonnie was from Moncton and listened patiently to her fears for her brother, fighting in Afghanistan. It was all part of Zev’s plan to determine where the good manuscripts were going.

The situation at home had gone from sad to bizarre. He found his mother’s pink slippers in the microwave and the toothpaste in the fridge. The poor old girl wore track pants all the time, and gave off a sour odour. After evenings on the front porch with his manuscripts, Zev stretched his legs in the neighbourhood. Twilight often found him at Shorty’s, head buried in the ice-cream freezer. The present Shorty, a Korean, was the man who’d discovered his father.

Zev ate his Nutty Cone on Dundas Street. A streetcar stopped near the Esso station, and a single figure emerged from it. The guy from the Parkdale Arms. Zev hid behind a payphone as Weiner walked off toward Roncesvalles. This was no coincidence, this was a warning.

Terrified, that night Zev lay sleepless, wondering if he should drive a taxi, like his old man. He could marry Bonnie and move her into Golden Avenue. He’d done his bit for CanLit.

At another reading the following week, a woman with a Scottish accent too thick to understand read poems about ghosts eating curries in the Shetlands. Zev contemplated the cracks in the soles of his shoes. Maybe too many people were writing these days, producing literature as weak as Mexican beer. And every day he expected the sheriff to lock him out of his office, or for Weiner to step out of the shadows and finish him off.

One Monday, Bonnie’s desk was empty when Zev arrived. With her betrayal now complete, Zev trashed all the manuscripts on his desk. Bedlam Books was all but finished. Pages covered the floor and drifted like snow into the outer office. He slipped on them when he came back in from lunch, sad that Bonnie wasn’t there to clean them up.

Later that week, after his telephone was disconnected, Zev started a list of what he liked in each manuscript. One had a matron named Rose who opens her house to runaways in nineteen-sixties Ottawa, though there was little else to recommend it. He liked the dialogue in All Night Gardening, a story about a boy and his father in a Maryland fishing village. Another author brought a whiff of magic realism to an Appalachian mining town. In The Fickle Dentist, linked stories about a Houston dental clinic, the characters shone even though the plots read like television hospital dramas.

Suddenly he knew what to do. Zev would create the stories and the author he needed to rescue Bedlam by plundering manuscripts of the characters, settings, and plots he admired. All he had to do was switch them around.

Armed with a highlighter, he got started right away. In one manuscript he liked a kitchen fire that kills the family cat; in another, how a Glasgow girl dispatches a romantic rival. One otherwise weak manuscript yielded a cousin who dealt coke; the next, a flowering magnolia in a southern town. Throw in some mid-nineties Montreal speed-metal bands, some asparagus soup recipes, and a car that won’t reverse. Your Journey Prize, Mr. Zevbrowski? Oh, thanks. Set it down there.

There was enough material there to write thousands of stories. This was mathematics rather than plagiarism, Zev rationalized, since he was only stealing ideas and not actual words. Night had fallen when he next looked up. Zev had before him the first story he’d ever written. Montreal had become Seattle; the nineties, the late eighties; and the magnolia, a white lilac. The first person narrative was fastest to write and provided, Zev hoped, an immediacy readers would believe took a rare talent to achieve. He named his effort The Wastepaper Basket, after the one on which his feet were propped.

In a week he had his template for literary success: take a character or two, invent some funny and sad things to occur, add a major issue and some clever dialogue. Keep the story and the sentences short, and sound a meaningful or melancholy note three paragraphs before the end. Resonance was key and resolution meant avoiding climactic endings and making sure the hero never got the girl/boy. Poetry would be even easier—he could just shuffle lines.

Zev started a list of elements to be included: cosmonauts, bondage, ice fishing, optimism, vampires, the Kabalah, land mines, pastoralism, and as many references to old television shows as possible. There were likewise things nobody wanted to hear about anymore, like incest, Catholicism, George W., heroin, and suburban sprawl.

Retro always worked. Using Bonnie’s calculator, he determined that a continually moving window of nineteen years, three months, eleven days and seven hours separated what was cool then from what was back in again now. Thus, Michael Dukakis and L.A. Law became obvious story points.

He wrote night and day, living on falafels and cappuccinos, and catnapping on the office couch. With Bonnie gone he could smoke at his desk, a right he hadn’t enjoyed in years. When he felt grotty, he took a bird bath in the washroom, stopping on his way back to pick up pages that had slipped into the hall. When he got stuck for dialogue he visited an Internet café, where he found that someone had meticulously posted the teleplay of every episode of The A-Team to the Web. His wrists ached, his laptop overheated, but still he typed.

In a month he’d cobbled together enough stories for a collection, many of them set in Alberta because it seemed to Zev that westerners were often lonely. This was the kind of artistic decision he’d learned to make. One afternoon he saw two men in mesh baseball caps and gingham shirts arguing over the open hood of an overheated Buick out on Spadina Avenue. His title came in a flash: Country Car Care Manual. He called his Web host to get the Bedlam site up again and found a printer who agreed to an initial run of eight hundred on a modest deposit. The proofs went out to reviewers with some stamps he found at the back of Bonnie’s desk.

The author he credited the work to was Warren Moran, a twenty-eight-year-old son of Canadian diplomats who’d lived in Myanmar and Italy. He’d attended Cambridge for his masters in comparative literature and had since taught English in Thailand and Peru. Presently, he was finishing a Ph.D. in French literature, at Columbia, and was also a much-in-demand D.J. on the European circuit. Zev chose the academic credentials to account for a formalism he’d detected in his own prose.

Yet what if someone wanted to meet Mr. Moran? Zev sauntered up Golden Avenue on a mellow evening considering the potential dilemmas his new author posed. His mother had fallen asleep in front of The Rockford Files, the oven crammed with plates of food. Because there wasn’t much to do until he saw the reviews, Zev would stay home with her for a few days. The tears came as he scraped blackened, rock-hard pork chops into the garbage. Creativity left him so emotional.

That night the summer heat and his own excitement kept him awake. He hadn’t felt this vital in years. Yet how to do a nine-city Canadian tour without an actual author? More problematic was what he’d do when the foreign rights were sold. By the time the first Go train rolled by, Zev had decided he’d hire an actor if it came to that.

His mother was dressed in a mauve suit when he finally came down, a sign she might be feeling better. “I’ve been waiting all the morning to make your breakfast,” she said. “What do you expect to accomplish sleeping so late every day? ”

Zev sat at the place set for him. It was possible that she hadn’t noticed he’d been away for a month. “Just one egg this morning, please,” he said.

“You should let me wash that shirt,” his mother said. “The collar’s looking very greasy.”

After she was gone, Zev packed up the manuscripts in the living room to bring them to the office. A novel from Warren Moran would complete Bedlam’s comeback. Then Zev would send Warren on a permanent vacation or, better, cook up a sudden, tragic death to spike sales. If he still couldn’t find worthy authors, he’d start writing himself and finally live the good life.

That afternoon he napped, the long hours of writing having worn him down, until heavy footsteps downstairs woke him. Weiner! Zev grabbed a slo-pitch trophy on his dresser and charged off to deal with the home invader.

Halfway downstairs he saw the police cruiser in front of the house. He let the trophy fall to his side. How had they found out so soon? Two big cops and a sallow man in a shirt and tie were with his mother in the kitchen. “Are you the son? ” One of the officers checked his notepad. “Are you Vinicus Zevbrowski? ”

“That’s me,” Zev said. “What’s going on? Am I in some kind of trouble? ”

“Your mother’s been caught shoplifting,” the officer said.

“It’s the third time this month,” the sallow man said. Zev now saw that his tie had the Loblaws logo on it. “She’s rude, too. I can’t keep pretending it’s not happening.”

“No, of course not,” Zev said, scarcely containing his grin.

“This is one last friendly warning,” the other officer said. “I understand there’s recently been a death in the family. Next time we’re going to have to lay charges. Understood? ”

“Definitely, officer.” Zev put a hand on his mother’s shoulder and waited until their guests were gone. “Ma, I thought you were going to Aunt Helen’s. Why didn’t you say you needed money? ”

“You don’t have any,” his mother said. “Anyway, it’s their fault—they charge too much for everything. Five dollars for chicken legs.”

Zev stayed at the table after his mother left to watch her afternoon soaps. If this were a short story, crucial decisions would have to be made about whether he and his mother would ever reconnect. He’d never seen so clearly how the creative process worked.

Another day at home was all he could take. Zev burned to write again, but first the new Zev needed an new image, especially if, without an author, he had to fill in at awards ceremonies or interviews. His last credit card was good for eight-hundred-dollars’ worth of baggy jeans, running shoes, and athletic wear. He even got one of those trucker caps, like a modern B. J. McKay. Properly outfitted, he’d be unstoppable.

The first reviews appeared that weekend. Two were glowing, and only one suggested that the stories were almost formulaic in their inventiveness. Zev also received three offers to profile this talented young author. Tears in his eyes, he explained that he would try to contact Moran, who was travelling in Mongolia. Yes, he was hoping for a novel from him. In the meantime, watch Bedlam Books for more fantastic new releases.

Great reviews were useless without an author. Back to work, then. Zev removed the staples and bindings from every manuscript in the office and piled them onto his desk. Then he flipped each stack onto the floor and dove after the mess, tossing pages into the air until they were all jumbled together. With a broom from the janitor he swept any strays in the hallway into the larger mess.

It was dark when he’d finished restacking the pages regardless of their original order. His first novel. All it needed was to be typed into his laptop and edited down. Zev was hoping for four hundred pages. Nothing too ostentatious.

A few days later he heard someone enter the outer office. The sheriff, finally. Now he’d have to get the manuscript pages back to Golden Avenue. But it was Bonnie who stuck her head into his office. “Jesus,” she said. “What happened to you? ”

“I should be asking you the same question,” Zev said. “Traitor. Where have you been? ”

“In Moncton, visiting my mother,” Bonnie said. “You know I always take September off. What the hell are you wearing? ” She took another step toward him, then placed a hand over her nose. “Oh my. Vinny, how long have you been in here? ”

“Long enough to get the job done.” Zev led her to the door. “You’re welcome to stay on, but you’ll to have to keep out of my office. Oh, and there should be some money in the account now, so don’t forget to pay yourself.”

It took three weeks to cut and paste the novel together. In it, a young American man teaching English in China learns that his parents have been killed in a car accident. He foolishly gets involved with the daughter of the local communist boss and the doomed peasant revolt she’s planning. Zev loved how he—or Moran, rather—contrasted the thematic bankruptcy of early-twenty-first-century Western culture with the austerity of the East.

Near the end of the novel, the hero is invited to Los Angeles to develop Who’s the Boss? for the big screen and leaves China torn in his politics and his affections. Zev had his hero detect a symbiotic relationship between LAX and the music of the Bangles, but couldn’t find a suitable ending. If no one else could write good endings, how could Zev? Yet the world could wait another week for what he had tentatively titled The Valedictorian.

Happily, Country Car Care Manual was receiving interest from U.S. publishers. Zev now knew using an actor wouldn’t work, and was having difficulty hiding the truth from Bonnie, who was being unusually friendly to him. It was true: women loved success. With money from sales he paid a month’s worth of back rent and got his phone reconnected. Some nights, anticipating the commuter trains, Zev dreamt of taking credit for the stories himself.

He wanted The Valedictorian to be thrilling rather than merely profound. Everything he’d read lately had been overly moving. Time passed. The evenings were too cool to read on the porch and leaves lay scattered along Golden Avenue. His mother was a ghost, oblivious to anything beyond the television. He had to get out, but the only way he could raise the money for a new apartment was to publish the novel.

In the absence of any new Moran material Zev held his nose and wrote the titles of five manuscripts on scraps of paper. These he placed in an empty coffee cup and closed his eyes as he made his selection. Yogic Hearts, presumably a romance, won. Zev asked Bonnie to draw up a contract, happy to see his girl busy again.

Within a week he had met the young woman author of Yogic Hearts and arranged for a first run of one thousand copies. Still, an ending for The Valedictorian wouldn’t come. He had the urge to tell his troubles to the books editor of a city paper he had on the phone, but to do so would destroy Bedlam Books. No one had told him a writer’s life involved so much loneliness.

As he put down the phone he heard a loud male voice in the outer office. A creditor, no doubt. They were creeping closer now that Bedlam was active again. He heard Bonnie shout his name and opened the door to find a man brandishing a manuscript backing a terrified Bonnie into a corner. Weiner! “Get away from her!” Zev shouted.

Weiner charged at him. As they skidded across the floor into his own office, Zev was overcome by the odour of unwashed clothing. Eyes watering, he pushed the crybaby author off him as Bonnie cringed near the door. At least she was safe.

The two men circled each other, Zev noting the vacant, zombie look in Weiner’s eye. “I want my book back,” Weiner said.

“It’s not here, Weiner,” Zev said.

“This is for me and every writer you’ve ever burned,” Weiner shouted.

The accusation paralyzed Zev. Could the weasel know his secret? Weiner used Zev’s hesitation to attack, his open hands landing weak blows on Zev’s face and arms. At last Bonnie showed her true colours by slapping at Weiner to get him off Zev.

Somehow, Weiner ended up on Zev’s back, his hands over Zev’s eyes. They careened into the hallway. Blinded, Zev spun out of control as he tried to throw the wailing writer off his back. He sensed daylight and fresh air ahead, then heard Bonnie’s cry. In the same instant, he banged into something and the great weight was lifted from his back.

Zev blinked into the sudden brightness. He had slammed into the railing of the fire escape, which had knocked Weiner off his back and into the laneway below. The late writer lay in a twisted pile atop the crumpled roof of a car.

Zev stared into the deep blue autumn sky. Bonnie stepped onto the fire escape, her arm slipping around him, her head nestling against his chest. He had earned his freedom, and the girl.

The rest of The Valedictorian came easily now. After establishing his hero working with Tony Danza in a Brentwood bungalow, Zev had the outraged communist boss send assassins stateside. An elaborate chase across L.A. ensued, with the hero rescuing his kidnapped secretary after eliminating dozens of Red Army specialists in a monumental clash at Anaheim Stadium.

A week later, Zev chose Red Dawn as a new title, cut much of the dialogue with the communist’s daughter, and changed China to India. Soon what he’d written earlier became a short prologue to the action sequences in L.A. It was sometimes necessary to provide a little back story.

Yogic Hearts turned out to be for people recovering from heart attacks. Zev had Bonnie arrange a promotion with the Heart and Stroke Foundation and the book sold so well that he started a series of health titles. To free up time to write, he made Bonnie vice-president of development. Unfortunately, saving the house on Golden Avenue didn’t provide her with much of a raise, and there was also the matter of leasing another Saab.

To celebrate the completion of Red Dawn, Zev put his refurbished reputation to the test at a Halloween evening of scary poems and stories at the Parkdale Arms. He ditched his Snug jeans and hoodie for a red cape and a blue T-shirt with a hand-painted “S” on it, relics from his student days. Worn under a black suit, with his white shirt open to the waist, he felt it was the perfect metaphor for the new Zev emerging from the old.

Unfortunately, no one else was in costume at the hotel. Zev was a day early. He had messed up his dates. Or Bonnie had. Writers can be so isolated.

The next evening, while shaving after his shower, Zev found his mother’s scarlet track pants hanging on the back of the bathroom door. They fit perfectly as tights, but were too short. He compensated by digging out an old pair of blue Doc Marten boots, tapping back into the energy of long-ago punk shows at the Apocalypse Club. Dressing up like a superhero was bringing out the kid in him again.

Still, he could go further. Deeper. He could bring out the real superhero. Zev donned the cape and T-shirt again, having dispensed with the suit—this was no longer about emerging—but it wasn’t enough. He found a pair of scissors and returned to the bathroom to hack off his ponytail and trim the rest of his hair. He stuck his glasses in the pocket of the track pants. Almost.

With his father’s tub of Brylcreem from the medicine chest, Zev parted his hair over to the side and used a comb to sculpt that single thick curl on the right side of his forehead. There. Just a second for it to set. Now he was ready.