Two men are here to sell us a vacuum cleaner. It’s the kind that sucks all of the dust into a reservoir of water and that promises to save all of the allergen-ridden, puffy-eyed children from a life of doom every time the house needs to be cleaned. That’s what the men told my mom. She’s the one who let them inside. I’m the nice young man who wheezes and needs a stupid Bionaire in my room, and whose stuffed animals are suffocating in black plastic bags in the attic because when I hug them they try to kill me—except I won’t die. That’s what Mom says while she puts the dental mask over my mouth, looping the elastic around each ear before firing up the vacuum cleaner she calls Big Betty.

“You won’t die. You just need to wear this.”

It’s snowing like a son of a gun outside, so when Mom opens the door and backs away to let them in the front porch, they charge at her with an incredible whoosh, scattering snow everywhere in big wet globs, shaking the snow out of their hair, stomping their feet. Everyone’s laughing like it’s a comedy. Everyone except for me.

I’m not shy. Mom says I’m wary. There’s an Elvis Presley song called “Suspicious Minds”; I definitely have one of those. The men remove the rubber protectors from their feet to reveal the kind of fancy leather shoes important people wear. There’s also a very large plastic suitcase sitting between them.

When people see the inside of our house for the first time, they say it’s “charming” and they make ooh and ahh sounds and say, “I used to live in a house just like this.” Not these guys. They don’t seem to have any interest in looking around, which is fine by me.

“You can set up in here,” Mom says.

Once her back is turned I race up to my room to grab my Knight Rider notebook and my lucky pencil.

The best place for keeping an eye on things is from my spy spot in the space under the stairs. We live in a character home. I don’t exactly know what gives it character. We don’t have any ghosts or anything like that, but the floor creaks when you walk on it, our attic has a trap door and a drop-down ladder, and there’s a cellar in the basement containing potatoes that have eyes.

One of the men rips open the suitcase with so much force the buckles splinter off, like it’s a plastic toy. It breaks into a million pieces, scattering everywhere like snowflakes. Mom’s face is covered with a bridal veil, so I can’t see the fear in her eyes when the man grabs her by the wrists. She’s a turkey wishbone and he’s going to snap her. “Make a wish, Mom,” I whisper. They force her inside the suitcase, like that magic act where they saw a lady in half, except that I can’t see her legs, or any part of her, all I can hear are her screams.

I believe in taking notes on all subjects because even though I think I will remember it’s surprising what I forget. Besides, Mom says it’s good for me to empty my head, because it gets really full. I’m using my secret agent eye trick. (If you need to see things far away you close your left eye real tight. Maybe if you’re right-handed it’s the other way around?) One guy is really short and round, but only when he turns to the side, kind of like the pictures I’ve seen of my mom when she was pregnant with me. The other guy is tall and skinny, like a piece of celery. They’re like Laurel and Hardy! I mind-message Mom, but she is staring at the man with the brown hose in his hand like her life depends on it.

“What type of vacuum cleaner do you have now, ma’am?”

Our Hoover lives in the linen closet. It used to belong to Grandma, but we inherited a lot of “crap” when she got “shipped off” to an apartment. When Mom vacuums it smells like dried flowers and burnt hair. “Oh no, not again. Not the incinerator!” I yell, my arms swinging over my head, charging through the house with my blue mask pulsing in and out. I make like I’m Darth Vader from Star Wars. Eeehhh. Ooohhh. Eeehhh. Ooohhh. But Mom can’t hear or see me; she’s caught up in making patterns on the floor. Mom is very graceful. She used to be a dancer, before Dad left us and started on “family number two,” and now she works two jobs to make ends meet. The only dance partner she has when I’m not standing on her feet is the beater bar. She swings the hose this way and that, and I run through the house like a superhero until she’s done.

“The unique thing about the Rainbow system is that virtually zero dust is emitted into the air, and there are no bags. It also has a powerful hurricane motor that grabs everything—including the things you can’t see.”

The skinny guy waves his hands around in the air like one of those Sunday morning TV preachers Grandma loves so much. Like Oral Roberts, but without as much hair.

“Dust is the devil,” but I love how on sunny days the sun lights it up so I can run through it, spinning it like those clusters of flies that hang around on really hot days in the summer. “Micah!” Mom yells. “You’re making it worse.”

I’m always making it worse. Not just at home, at school, too. At school my seatmate is Darcy. We’re in a split 5/6 class. She’s dumb. Like dumb dumb. Not just bad at fractions. We’re stuck at the back of the classroom—for our own good. There’s a box of tissues on our desk on account of her nose being so snotty. It’s a border: she’s in the U.S. and I’m in Canada. Sometimes the box moves and her elbow touches my elbow, so I put four small dots on the desk in permanent marker. Now we don’t fight about it anymore.

In the winter, Darcy’s nose boogers get crusty and block her nostrils and she breathes in and out of her mouth and makes me go out of my mind. Last Wednesday, when I was going out of my mind, I spied a piece of chalk on the floor. I rubbed it on the metal part of my chair and started sliding around. I was having so much fun, I decided to circle around the desk, just as Darcy stood up. I crashed into her. She went down like Jesse Ventura in W.W.F. Except she was wearing a dress and I could see London and France. She didn’t know because she was down for the count, but when the rest of the class saw, they yelled gross things and said she was going to be brain dead. Mom got called at work to pick me up. She wouldn’t even look at me.

“Get in the car, Micah.” I wanted to rest my chin on my knapsack but I didn’t because I needed to be punished. Instead, I looked at the side of Mom’s face, tracing its edges like that silhouette art project we did. I would have gotten an A+.

All of the bad things get sucked up by the vacuum cleaner, but good things do, too: my Lego, the backing to Mom’s diamond earring, Cheerios. Mostly though it’s the stuff we don’t want to look at, like hair and spiders and little stones that get tracked inside on our shoes. “I’m always amazed how heavy this bag is,” Mom says when the bag gets full and the vacuum cleaner screams extra loud.

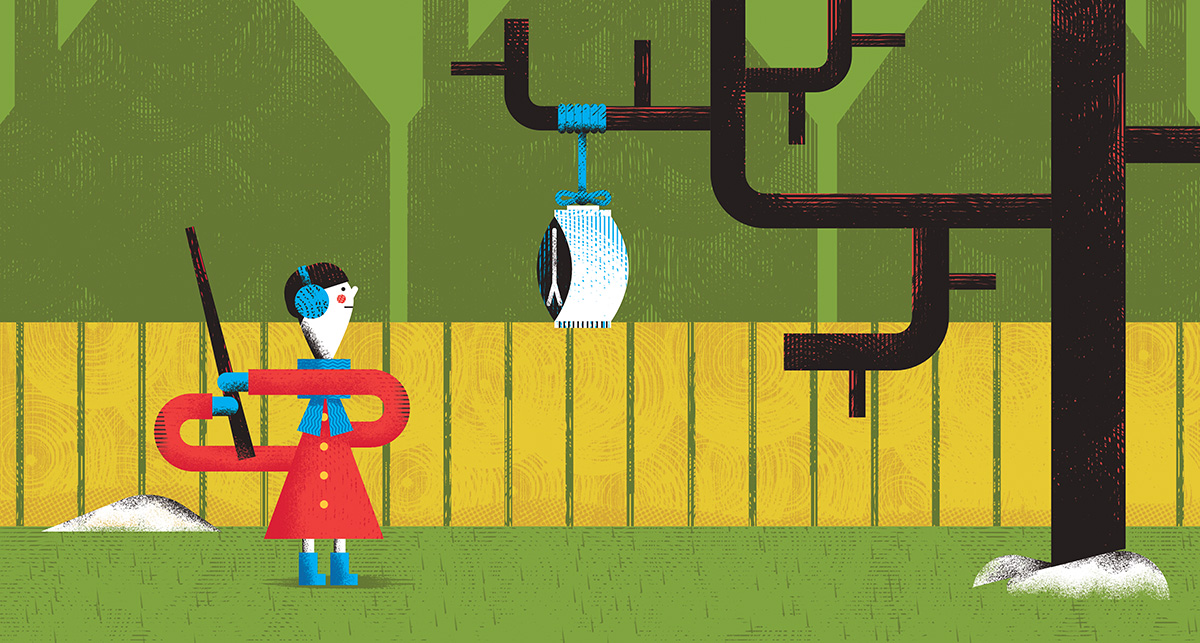

Once, I asked Mom if I could take the bag to the backyard and tie it up to the tree like a piñata and smash it with our broom and set all of the dust mites free. I know about dust mites because I had to go see a specialist because of how bad my ears get. Sometimes they ache and get so plugged I can’t hear, which means I can’t sound out words, and for a while I had to leave regular class for one-on-one study with a lady who tried to poke my eyes out because of how blue they are.

“She’s pregnant, sweetie. Being pregnant can make you a bit crazy,” Mom said. Anyway, the specialist showed us the scary-looking dust mites in the dark on a black and white screen and explained that they’re everywhere but “completely invisible to the naked eye.” Once I knew it was the bugs that were making me sick, I used an entire can of Raid in my room to fix it once and for all, but then Mom took me to the hospital because of all the poison. The doctor decided to keep me there and removed my tonsils and adenoids, and boy did it hurt to swallow. All I wanted was ice cream. The nurses were so sorry but all they had was Jell-O. It jiggled in my throat. They told me not to blow my nose but when they left the room my mom let me blow my nose into a tissue she found in her purse that had lipstick on it. Then we both cried because blowing made everything worse.

Some days Mom cries a lot and won’t leave her room. Hearing her crying makes my insides hurt, so I call Grandma. Grandma comes and whispers through the keyhole, and eventually Mom comes out. Her eyes look like they have balloons under them. They sit at the dining room table and drink tea. Grandma says things like, “It’s not the end of the world” and “Suck it up, buttercup.” After they’ve drunk all of the tea in China, Grandma leaves and we have a quiet dinner. I like it better when it’s just the two of us.

“How much does it cost?” Mom asks one of the salesmen.

The short man shifts from one foot to the other, resting his elbow on the chair. The skin on his elbow is purple and cracked like a scab that needs to be picked off. His socks are also purple, with stripes. “Well, it depends if you get all of the attachments. I could give you a special deal if you like, little lady. Maybe we could throw in our all-natural air freshener, too.” This seems to make Mom feel better because I can’t see the line in the middle of her forehead anymore. She calls it her worry line, but it might as well be named after me.

I flip to the last page in my notebook and add “Little lady” to “Things People Call Mom”: Ma’am, Marcelle, Marcie, Mar-Mar, You little tart, Hey you, Ya dumb broad, Sugar, Lovey, Micah’s old lady.

The short man slumps to the ground. His head makes a dull sound as it hits the hardwood floor, rolling to one side. His hair is stringy and slicked with sweat. His eyes wide open, like aggies. he will never blink again. The other man scrambles to his side, yelling his name over and over: “Frank! Frank! Are you with me, boy? Don’t go, Frank!” and he throws himself down on the man’s chest and sobs and sobs and sobs until his head melts.

Because of what happened at school and what Mom calls “strange behaviour,” she took me to see the Boogie Man. The Boogie Man lives in a tall office building near the lake. We had to take an elevator to the twentieth floor. I held my breath the whole way up.

Guess what? He tells me I’m normal. He tells my mom I’m normal. He probably writes “Normal” on the yellow pad of paper sitting on his desk. “You have a bright future,” he says, clicking his pen. Click click click. Bright bright bright. What I don’t tell the Boogie Man is that at night, when I close my eyes, I see smashed-in faces with drooping mouths, jagged teeth, and skin hanging off bones. It’s like fast-forwarding that movie about sharks I saw at Luis’s house. I don’t tell him any of this because of what he’ll write down, because of what he’ll tell Mom when I’m sitting in the waiting room, counting the ceiling tiles to calm down.

I wish I could make the bad stuff stop, but all I can do is wait it out, like when my neck goes hard from pulling Gs on the Tilt-A-Whirl, at Chippewa Park. I’ll lay on the grass until the world stops spinning and my neck is soft again. Sometimes my imagination plays tricks on me. Like when I’m riding my bike in the summer and I get to the crossing two blocks from our house and I see the strange white van with no windows (Luis says it’s a raper van) and I imagine that it hits me. I’m flying but I never land.

For a while Mom dated a guy named Luke (I don’t know why, but he liked it when I called him Cool Hand Luke). Luke was hit by a car and has a prosthetic hand. He can’t feel anything. Even when you poke his fingers with sewing needles when he’s sleeping. I want to know what that’s like. The not feeling anything. He hugged me when I fell down the stairs on account of me wearing my super slippery sleuthing socks. That’s when he told me about his own accident with the car. About how he broke his shoulder and a couple of ribs, and tore the nerves and tendons in his hand. They had to amputate it. Which is just a grown-up way of saying they cut his hand clean off.

Luke always smelled of smoke. When he hugged me that time, I didn’t mind the smoke like I usually did—maybe because it didn’t give me a tickle in my throat. I do remember how hard his muscles were. They were so hard I could feel them through his thick denim jacket. Before that moment I’d only ever hugged Mom and Grandma. Hugging Luke was different. I never wanted him to let me go. I wanted him to carry me everywhere—to get groceries, to the baseball diamond, to see the stars light up the sky at Hillcrest Park. I knew he could do it. I knew he would never get tired. That I would never get too heavy. Everyone would think we were cool and not freaks, like a travelling ventriloquist duo at the circus. People would come watch us and eat cotton candy until their fingers and tongues were blue and sticky. I wouldn’t have to worry about how it sounded when I talked. I could just open my mouth and let all of his thoughts and words pour out instead of mine.

Mom dumped him. Luke didn’t dump Mom. That’s what Grandma said. I really liked Luke, but when Luke was around a lot so was Grandma. Mom would kiss me goodnight and in the morning Grandma was there asking me what I wanted for breakfast, which is a silly question, because I’m always going to say, “Thin pancakes with crispy fried edges, please.” If Mom still wasn’t home by lunchtime, we’d walk to McKellar Confectionary for Coney dogs, because I’m a growing boy. Sometimes we’d get them to go in a brown lunch bag, other times we’d sit in one of the booths and eat them from oval plates. I’d get mine without onions: n-o. They’re especially good with chocolate milk. The bad part about eating lunch with Grandma is having to make conversation with Grandma.

Questions Grandma asks that I will answer:

1. How is your hot dog? Did they remember not to give you any onions? I hate when you ask for no onions and then you get onions anyway, even if it’s just a tiny bit of onions. I mean, what if someone was allergic to onions?!

2. Do you think it will snow today? It clouded over awfully quickly.

3. Those are nice mitts. They look handmade. Where did you get them?

Questions Grandma asks that I will not answer:

1. How is school? The last time I saw you, you were working on a science project. Did you get a good mark?

2. Has your mom been to see Rod?

At this point I shovel in the hot dogs like I’m in a hot-dog eating contest, bugging my eyes out and half-pretending that I’m choking.

“Micah! I wish you wouldn’t eat your lunch so fast. You’re going to have stomach troubles later in life.”

Works every time.

Did I tell you my name is Micah? Mom named me after a prophet. I think that’s why I can see into the future.

The short man draws a knife from his pocket and slices it across my mother’s throat. A thin line of blood appears, like a paper cut. She goes paler than pale and the man catches her in his arms as she slides to the ground. She’s a goner. I scream, but it sounds like a squeak. They run and so do I, but they are faster because their legs are longer and that’s just the law of physics. Eventually we become outlaws together, riding off into the sunset in their beat-up station wagon. It’s as though my life before Mom never existed. Like using Wite-Out to hide a mistake.

The big guy reaches into his pocket for his wallet, pulls out a card, and hands it to my mom.

“Give me some time to think about it,” she says, as I skedaddle out of my spy spot and walk to the kitchen to get a glass of milk.

“Oh, hey, Mom.”

“Micah, there you are! Frank and Julian were just leaving.”

Up close the Rainbow Men look different. Their faces have more lines in them, like cracks in pavement. But their features are sharper. Frank’s round belly is pushing against the buttons on his shirt and Julian’s leather belt looks like it’s been left out in the sun.

Once they’re gone, Mom takes out the broom to sweep the dining room. I watch the back end of their car, which is crusted over in ice and mud. I can’t make out the license plate number. “APJ E6—.”

“How about sweet and sour meatballs for dinner, Micah? Would you like that?”

Sweet and sour meatballs on white rice is my favourite.

Mom’s got her back to me and I throw my arms around her in a great big bear hug. Grrrrrr. She is a bear and I am a bear. But really we’re only bears hugging in my mind.

We have dinner. We don’t talk about anything bad. We don’t talk about Darcy, or the Boogie Man, or Grandma. She keeps a Safeway flyer beside her at the table and writes on it between bites of food, before sliding the pen behind her ear. I sneak a look at the numbers but I can’t make sense of them, and not just because they’re upside down.

“How would you feel if we got rid of Big Betty?”

“I don’t care,” I say. “But what about Grandma?”

“Oh, she won’t be thrilled. You know how she can get. Maybe we’ll have a yard sale in the spring and try to sell it along with a few other things. It’ll help pay for the Rainbow.”

I like yard sales. I like browsing through records and 8-tracks, trying on leather jackets and smelly old shoes, and sometimes there are even stacks of girlie magazines. Luis says they’re worth their weight in gold.

The vacuum cleaner takes three weeks to arrive. It has a two-year warranty in case anything breaks. I was hoping the Rainbow Men would deliver it to us so I could see them again. Instead, Mom and I stand in line at the post office to sign for the parcel with our delivery notice. A nice man helps us get it to a shopping cart and says, “Anytime, sweetheart” to Mom after helping us push it through the slush, strapping it to the inside of the trunk because it won’t close. We don’t talk on the drive home because of the snowstorm, because of how the wipers are going a million miles an hour. I try to count the swipes, but I give up after a hundred.

We lug the vacuum cleaner inside. The edges of the cardboard box are soggy and fallen in like that time I tried to bake a cake for Mom’s birthday.

“Oh good, the warranty,” Mom says, lifting a limp piece of paper out of the box and stuffing it into our junk drawer.

“What’s a warranty?”

“A warranty is like a promise.”

Then I ask Mom why the vacuum cleaner is called a Rainbow and she tells me about the flood in the Bible and how a rainbow is a symbol that God gave us to say he would never send another flood to wipe out the earth ever again. “The rainbow was his promise.”

What I want to know now, but don’t ask, is why there are still floods. Not where we live but in places I’ve seen on TV. The number of people who die climbs the higher the water gets. Trees bend over like they’re made of rubber, water goes from blue to brown, and people sit on the hoods of their cars with their dogs and cats.

Mom says our Rainbow vacuum means a new start for us. She looks happy. I know this because I can see all of her teeth when she smiles.

Now when Mom vacuums she insists on showing me the disgusting things in the water. “Micah, come here! Would you just look at this?” I’m surprised how much of Mom’s hair is in there—it’s wrapped around everything. Once we’re done looking at the water, we flush it down the toilet. It’s like a flood in our bathroom every Saturday.

And when she asks me how I feel now, I tell her that I can breathe better, and that I don’t see things that aren’t there. That yes, I would like to take a road trip, and no, if I fall asleep in the car I won’t scream about the ugly things that live behind my eyelids. I promise. I don’t tell her that, in order to make me feel better, instead of the scary flashes, I see her dancing. Sometimes the two of us together, my feet on her feet, my hands in her hands.

Sometimes, though, she’s all by herself, her long black hair swinging from side to side, her eyes closed, just her and the Rainbow. Nothing else.