Just outside of Washington, Our Lady of Mercy Rehabilitation Center is surrounded by a thick wall of tall leafy trees.

“Is it only for men?” I ask as we walk from the parking lot. Fluke has been a resident here five months now. This will be the first time either of us has seen him since Vincent and Carla’s wedding one year ago last week. Part of me wonders if this visit will do little more than dredge up more misery.

“It’s mixed.”

“You said it was built for clergy members?”

My brother nods. His sigh is implicit.

“Then how can women be staying here?” My accusation is implicit.

He looks straight ahead as we walk up the circular drive in front.

“I said this place was for priests and religious, and nuns are religious.”

I keep my mouth shut. Our family is only nominally Catholic. All of us but Vincent, who is so Catholic you’d think he was a convert. Carla converted. She wasn’t much for religion but she was baptized in our mother’s living room, two hours before the wedding.

Perspiring under the weight of his robes and the August heat, Father Luke led Carla through the sacrament. This was the first time I had ever seen Fluke on duty. He crossed Carla’s forehead with holy water and whispered, “I don’t want to mess your makeup.” His own lashes fluttered as rivulets of sweat trickled into his eyes. It was warm but none of us was sweating like Fluke.

I had dubbed him “Fluke” on the rooftop patio of the seminary as the three of us stared out over Washington, getting drunk on Russian vodka. Luke’s ordination was coming up soon.

“One more month and you’ll be Father Luke. ‘F. Luke,’” I said. “Fluke!”

“You got that right, sister.” Luke glanced at his watch and set down his empty glass. “Four weeks until I take the ontological leap. Who’s up for male strippers?”

A grim smile crossed Vincent’s face. He looked out past the railing to the basilica in the distance.

“Oh puh-lease, Mother Manguard,” Luke needled him. “Don’t be such a stick-in-the-mud!”

I grinned and flicked an ice cube at my brother. My dear and earnest Vincent. He had just begun Year 2 of his theology degree and it stuck him like a blade, the sight of infidelity rewarded.

“There he is,” Vincent says. “Is that a Bible in his lap? He looks positively pious.”

I spot Fluke seated on one of several moulded orange chairs in the portico. Black hair lacquered, he has a large book in his lap and a cigarette in his hand.

“Well, well, if it isn’t Father YouTube,” Vincent calls out.

I wince. My brother must think it’s better this way. Better to chase the elephant out of the room before it makes itself comfortable.

“You’re here!” Fluke’s voice is frail. Closing his book, he sets it down on the cement and lifts himself carefully out of his chair as though nursing an injury. Twenty-eight going on eighty.

He switches his cigarette from one hand to the other and then opens his arms wide. The sheen on his eyes suggests tears are brewing.

“Sorry. I’m still smoking,” he whispers as I step into his embrace.

He smells of soap and nicotine. His polo shirt is damp and my mind flashes back to Father Luke performing the sacrament of marriage, skin florid and glistening as he joined Vincent’s hand with Carla’s and pronounced them a couple.

Fluke lets me go and turns to Vincent.

“Hey, brother. How’s it going?”

I am struck again by the way the guys from Saint Michael’s Seminary embrace in such an unabashed way. Not the usual one-armed man-hug severed with a backslap.

Once our greeting is complete, Fluke glances around as though he’s forgotten his wallet.

“Let’s sit,” he says. “Gosh. Take a load off.”

He adjusts a second orange chair for me. Vincent pulls one closer for himself.

“I’m on so many meds, I can’t remember my own name never mind my manners.”

“What do they have you on?” I study him: his hands and his eyes, the cadence of his speech.

“What don’t they have me on? Let’s see . . . lithium. For my bipolar. I was diagnosed years ago but I wouldn’t take the meds. Gained too much weight. Different doctors, different approaches, but still, here I am on lithium and I look like Rosie O’Donnell. I take eight hundred milligrams two times a day. I think. And . . .”

I glance at Vincent. His left eyebrow is slightly arched. Rooting in my purse, I ask if I can write down the meds.

“I want to look them up. I’ve got a focus group coming up with physicians and mood stabilizers.”

“Mood stabilizers, yup. Three hundred milligrams a day.” He spells “Seroquel” for me. “And Lamictal, that’s an anti-seizure, and, um, Klonopin . . .”

He lights a cigarette, tilts his head back to exhale.

“My sister says this kind of dosage is crazy. She just graduated. Full-on nurse now.”

He looks at my notebook.

“You still working at the focus group place?”

I nod and print “Klonopin, 4 x 1 mg/day.”

My brother adopts a wry tone when the subject of my work comes up. “She’s still there. Recruiting angels to dance on the head of a pin for fifty bucks a pop.”

I look up from my notes.

“The smokers got two hundred bucks last week. So ha!”

Consumer Focus and Research pays people in the community to come in and try products or ponder advertisements and express their honest opinion on what they see, taste, and hear. I started there as a recruiter right after high school. I have since become a moderator. My job involves the facilitation of conversation among participants for surveys and focus groups. Our slogan is Your Opinion Matters. Sometimes, I’m asked to stand behind a two-way mirror with the client, observing the reactions of our participants—still my favourite part of the job. Few people get to fulfill their natural desire to be a fly on the wall. My brother may hold fast to theology, but I have come to believe that one can find meaning in careful analysis and interpretation. It’s a science that is pragmatic and yet hopeful.

“Speaking of dancing,” Vincent says, “last time we saw you, you were the most downloaded priest on the Internet.”

Fluke blows a stream of cigarette smoke.

“My sister said I was No. 1 on YouTube for two hours. Good Morning America was parked on my parents’ front lawn after the whole thing broke. Fox News. The Today show. My poor parents.”

Back in February, Vincent had walked into the living room where I lay sprawled on the couch. After everything that had happened to him in the previous six months, I had grown used to his flat, lost tone. But now there was a sudden heat to his demeanor.

“Google ’Father Luke Drunk Priest.’”

It sounded like an order. I reached under the couch for my laptop.

The headline was everywhere: “drunk priest propositions cops.” Video footage was leaked: Father Luke chained by one wrist to the white brick wall of a drunk tank, shouting, “Get these fucking cuffs off me, lousy shits!”

Standing in a beige linen suit, bright orange socks, and a pair of buffed loafers, Fluke yanked at the chain, convinced he could free himself. After a while he changed tack and began to beg. “I’m not an animal. Let me go. I’ll do whatever you want. Want me to suck you off? Be your boy toy? Because you can go fuck yourself is what. I’m innocent. Police brutality!” Each news agency that aired “the proposition,” cut the tape just before Fluke’s refusal to comply. They did, however, run excerpts of cries for his mother and his subsequent rendition of “When You’re Good to Mama” from the musical Chicago.

“Jesus,” I muttered, staring at the screen.

“He doesn’t want to be a priest,” my brother said. “He wants to play one on TV.”

Vincent stormed back into his bedroom. “They’re going to eat this up.” The media, he felt, were gunning for Catholic priests.

“What was with those fetching orange socks?” Vincent asks now. “Were you out deer hunting that day, Father Fudd?”

Fluke snorts.

“That could’ve been my audition reel. Celebrity Rehab with Dr. Drew: me and Janice Dickinson.” He rolls his cigarette ash on the edge of the standing ashtray. “Although, really—there were only four of us at that so-called party and I had one glass of champagne. I should have stayed home.”

According to the Portland police, Luke was three times over the legal limit and behaving aggressively. They needed to digitally record the situation, they said, for “safety reasons.”

“When the video went viral,” Luke continues, “my lawyer doubled his fee. Asshole. The new guy’s good. When I’m ready, he wants to slap a civil suit—Oh hi, Dr. Baker.”

We turn our heads to see a tall, angular woman trotting toward us. In her fawn-colored trousers and matching jacket she reminds me of one of those leggy hunting dogs. I swish the hem of my cotton skirt to catch a little breeze and wonder how she can stand being encased in so much fabric.

“Hello, Luke.” The yellow shirt she wears gives her an insistently cheerful look. She strides up to our small circle and clasps her hands together. “How are you this afternoon?”

“Very well, thank you,” Fluke says, sitting up a little straighter.

“I just wanted to check on you, make sure you weren’t stuck out here talking to reporters.”

Her eyes prick at the notepad in my hand.

“Oh!” Fluke laughs. He snuffs his spent cigarette in the ashtray. “Dr. Baker, this is Vincent. We were in the seminary together, and this is his sister, Ella.”

Up on our feet, Vincent and I each extend a hand. Fluke stays seated.

“Nice to meet you. Have either of you been here before?”

“First time,” Vincent says.

I watch her posture, note that she never crosses her arms, and the fact that she makes eye contact. This is a woman who is comfortable stating her opinions, one who does not fear reprisal.

“Has anyone talked to you about confidentiality?” she asks.

“Everything you see stays here,” Fluke recites. “Everything you hear stays here. Hear! Hear!”

“That’s right.” She smiles

“We’re aware,” Vincent assures her.

I look beyond her to a man sitting on a sunlit bench on the other side of the circular drive and wonder who might be here and for what sorts of addiction.

Dr. Baker excuses herself. Fluke thanks her. We sit in silence as she strides back up the walk. Once she disappears inside the front door, Fluke exhales and plucks himself a fresh cigarette: “What kind of reporter wears white socks?”

I look at Vincent’s ankle, and snort at the stretch of sport sock between his jeans and black shoe.

Luke stares at the building’s front door.

“I can’t shake the feeling that I’m in trouble now,” he says. “I don’t know anymore. It says ’histrionic’ on my chart. That, and ’agoraphobic.’”

“Agoraphobic?” Vincent says. “Does that mean you can’t wear fuzzy sweaters?”

I laugh and then stop. My brother’s smile is almost a sneer.

Luke blinks at him a moment.

“Ha! Yes. Fear of the fuzzy. . . . It also says ’paranoid.’ They got that right. Before I came here, it got so bad I was scared to go downstairs after the liturgy. We always had a little snack and coffee afterward. But I would run upstairs and hide in my room. I was scared when the phone rang. E-mail made me feel as if someone was in my house. Dr. Baker wants to bring the lithium down, but I feel good now. I don’t want to change anything.”

I look from Luke to Vincent and think about some of those agency meetings at Consumer Focus, the steadfast belief that desire is shaped by fear. To sell a product, they believe, one must begin with the realization that a person becomes devoted to a thing, a place, another human being when he fears what life might be like without it.

“They do a big assessment when you first get here,” Luke continues. “They even asked me how many sexual partners I had last year.”

I lean forward a little in anticipation.

“Seventeen.”

“Seventeen?” I repeat.

Vincent keeps a placid face, but I recognize the flint in his eyes.

“The therapist said that even if I were a layperson she’d still recommend Sexual Compulsives Anonymous.”

Luke looks at his dwindling cigarette and reaches for the pack. He lights a new one with the embers of the old.

“I’m not a sex addict. I just like having sex.”

One night at Saint Michael’s Seminary several of us sat on the rooftop patio, drinking vodka and gossiping. Many of the young seminarians were recruits from the Ukraine. Like barely pubescent boys, none of them met my glance or sent a word in my direction.

“So,” Alexander called across the table. “Did you read the New York Times this morning? The pope is sending his army.”

“Bah!” Vincent said. “They’d lose half their seminarians.”

The New York Times had run several stories lately, articles that told of an impending witch hunt. Apparently the pope would soon be sending his minions around the Catholic world to interview priests-to-be and root out the homosexual element.

“Vincent,” Rudy chimed in, “are you hiding any homosexuals under your bed?”

“I keep ’em all in the closet,” Vincent quipped.

“No homosexuals in this place,” Alexander said. “Only heretics.”

“Those fuckers fuck with me,” Luke waved his cigarette around, “and we’ll see which newspaper receives a picture of which bishop with a big fat cock in his mouth. Tout de suite!”

I coughed.

“Luke, honey, you’re killin’ me.”

“Saint Michael’s Seminary,” my brother mused, “a bastion of refinement and reverence. Speaking of which, the Giants are playing this Monday. Any of you knuckleheads going to watch the game?”

“Knuckleheads?” Alexander repeated. “Knuckleheads!” He laughed. “I never heard this. I like this one.”

Beside me, Luke took long pensive drags off his cigarette. Arms crossed, he stared down at the table.

I gave him a playful shoulder butt.

“How you doin’ over there?”

He pushed back his chair and headed inside to the lounge. Through the glass door I watched him wind his arms over the top of his head and then drop them at his sides again. He faced the patio. Then, catching my gaze, he reached over and turned off the light.

I glanced around the table. Vincent and the rest of them had segued into a discussion of various power brokers in the church. I stepped inside just as my brother was saying, “Christ didn’t call them a brood of vipers for nothin’!”

It was dark in the lounge but I could see the cherry of Luke’s cigarette glowing.

“Hi, Ella,” he murmured. He leaned against the wall near the light switch.

“Want some company?”

“I was just going to my room.” He mashed out of the nub of his cigarette in a saucer on the table. “Come on. I want to show you something.”

Following Luke down to the second floor I wondered if it was against seminary rules for a visitor to go into a man’s room like this. I didn’t suppose it was women who concerned Luke or his rector though. Still, I glanced up and down the hall while he put his key in the lock.

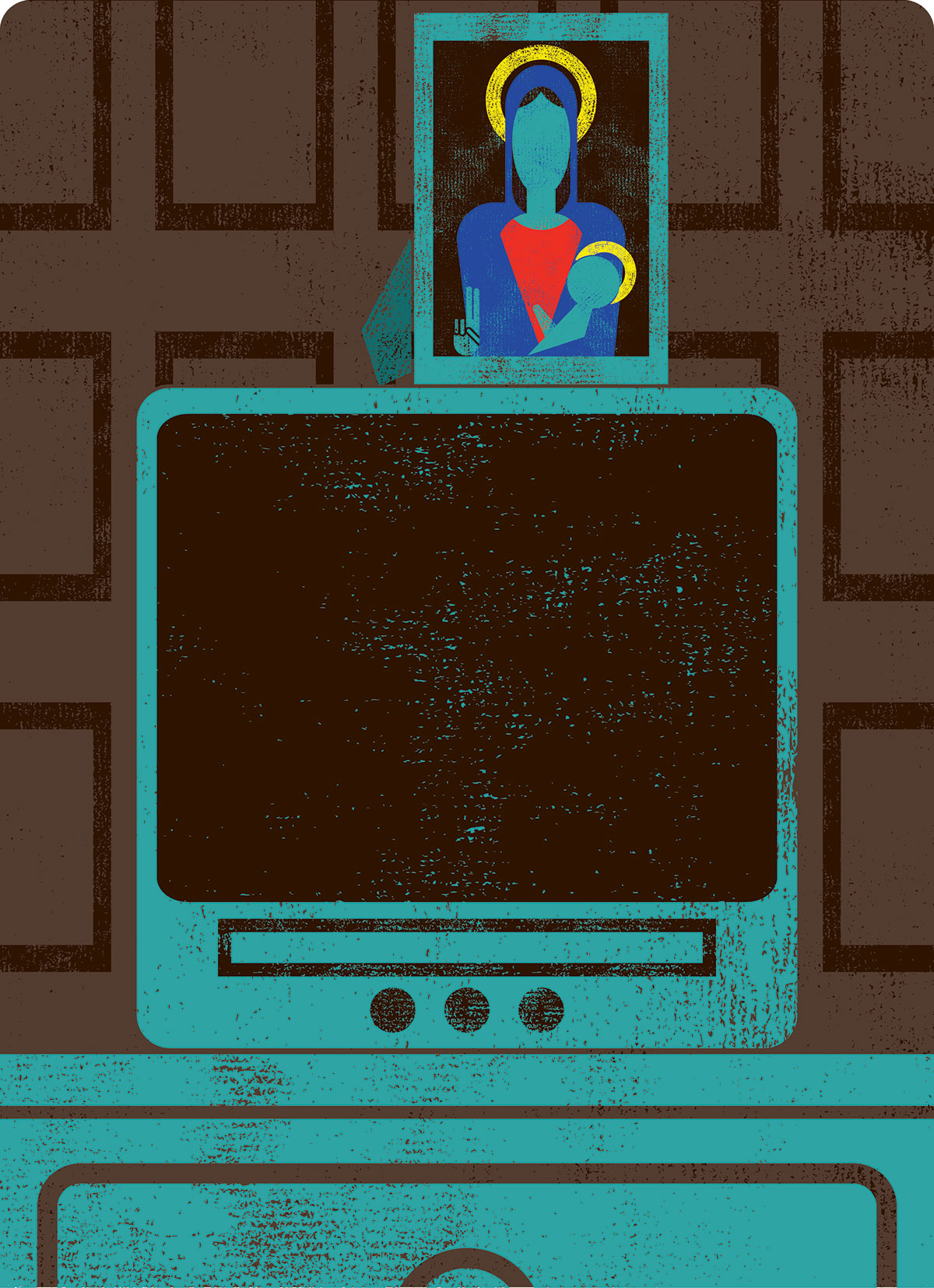

As I stepped over the threshold, he switched a lamp on. Dim light filled the small room and my eyes opened wider. Luke sat down on his crisply made single bed and I turned in a slow circle, peering into the faces of countless saints. Nearly every inch of all four walls was covered with a small wooden plaque, painted in golds and ambers, each one depicting a sacred event or a holy person. Up until this moment part of me had wondered if this seminary stuff was just a lark for Luke, something he was trying on—like an amusing but not very versatile hat. Now, staring at the doting eyes in icon after icon, it occurred to me that the man who slept here craved salvation the way some crave food or sex.

I looked at Luke. The top drawer of his nightstand was open. Perched on the edge of his bed, he stared at the front of a Christmas card. The edges were worn, as though it had been held daily. He set the card in his lap and opened it. Inside was a photo. After a few moments he lifted the picture and held it gingerly between two hands.

“This is Frankie,” Luke said softly. “They named him after me.”

Sitting down beside him I found it difficult to pull my gaze from the somber faces of the men and women on the walls.

Luke exhaled.

“Frankie was my nephew.”

He turned the picture toward me. A little boy in his puffy winter suit stood knee deep in the snow, grinning and pink-cheeked.

“He fell.” Luke squared the picture to himself again. “He got up on the sill, put his little hands where he thought the window would be and fell all the way down. Four storeys. My sister’s been sober ever since.”

“Oh Luke. I’m so sorry.”

“He was only three years old. When I feel like shit, I come in here and look at him. He was the sweetest, kindest little boy. And they named him Frankie.”

“I bet he was crazy about you.”

Luke set the photo back inside the card and slipped it back into the drawer of his nightstand.

“Sometimes,” he said, “they refer to Saint Luke as ’the physician.’ I thought, when I took this name, somehow it might be healing. ’Physician, heal thyself,’ huh? So much for that.”

Reaching down, he opened the bottom drawer from which he pulled out a carton of Marlboros and grabbed himself a fresh pack. Sitting up, he picked at the Cellophane.

“What’s going to happen when they come?”

“Who?”

“Ella,” he whispered. “We’ve known each other since we were kids, but I feel like we’re just getting to know each other now.” He stared into my eyes. “I’m gay.”

The sight of little Frankie in his neatly pressed shirt came to mind, his red lips, his hair groomed, slick as a mannequin’s.

I glanced around at the icons again. Nobody craves this kind of company without reason.

“I know, honey,” I said. “I picked up on that. I guess I did back then too. I just didn’t have the words.”

His eyes brimmed and a tear trickled down. He wiped a hand across his cheek.

“What if they pick up on that? My whole life—since I was a little boy. This is all I ever wanted.”

“It’ll be O.K.”

I tugged the cuff of his shirtsleeve, unsure what else to say.

“If they find out . . .” He wiped another escaping tear. “Some people aren’t as progressive as you. Even Vincent. I love Vincent. He’s the best thing to happen to this place, but I wonder how he’d feel about me if he knew.”

I kept my voice gentle. “He knows.”

Even the thirteen-inch television sitting on Luke’s bureau had a Madonna and Child icon set on top. The baby looked more like a tiny, knowing man standing in her arms. One of his hands caressed her jaw.

“Why do you stay here?” I asked, keeping my eyes on Mother Mary. “You could go over to the Episcopalians. It’s the same thing except they’re O.K. with gay.”

“You know what Bette Davis said?” Luke looked up at the Madonna too. “Gay liberation? I ain’t against it, it’s just that there’s nothing in it for me.”

“If your parish would take you back, would you even want to go?” Vincent peers at Fluke.

“They want me back,” Fluke says, his voice frail again. “It’s pointless though. I can’t say mass. I’ll burst into tears. Every time I think about it, I’m doing this.” He pops an imaginary pill in his mouth. “What good is a priest who can’t say mass?”

Vincent watches him.

“It might be tough the first time. Find some priest friends and have them concelebrate with you,” he suggests. “Anyway,” and his voice now takes on the sharp grit of gravel under tires, “it’s about community, not about you.”

Luke looks away. He grimaces as he rummages for cigarettes. He shakes the empty pack, then crumples it.

“My court date is set for ten days after I get out of here.”

“What does your lawyer think?” I ask.

“This will be my third D.U.I. They could give me three years.” He inhales a shaky breath. “I’ll leave the country if that happens. I’ll go to Brazil.”

“Oh yeah?” Vincent says. “You got a certain someone down there?”

My eyes snap to my brother’s. He looks as if he’d like to throttle Luke, wring out every squandered opportunity.

“Has your family been out to visit?” I blurt. My forced breezy tone sounds ridiculous.

Luke shakes his head. “I didn’t want them coming all the way out here. You’re my first visitors.”

Vincent blinks down into his hands.

“I’m so grateful too. I wish I could sit out here with you all day.” Luke sighs and glances at his watch. “Vespers in half an hour though, and we’re not allowed to show up in shorts.”

My brother looks up, as if he’s been caught off guard. When the three of us stand, his smile is lopsided.

Walking us back to the parking lot, Luke jams his hands into his big khaki pockets. Nobody speaks until we reach the car.

“This has meant so much to me,” he says. His lips purse and tremble slightly.

At the car, Vincent’s stance is wide and he sets his hands on his hips as though he is preparing for a punch in the stomach.

“I’m glad we came too,” I said. “It’s more relaxed than I expected. I thought they’d search us for contraband.

“Nah. All they care about is confidentiality. You can slip me crack, booze, heroine, just don’t tell anyone who you saw here.” He opens his arms to Vincent. “Brother,” he says, “thank you again for coming. From the bottom of my heart.”

Vincent’s eyes become wet and he throws his arms around Luke.

“You’ll get through this. I love you, brother.”

Over Luke’s shoulder, a quiet smile smooths Vincent’s face and the sinking sun casts a light that brings out the sad, liquid blue of his eyes.

They step apart. Luke looks at me. “Oop, you’ve a got an—”

“Eyelash,” Vincent says. “Hold still.” He touches my face. When he takes his hand back there’s a tiny hair on his thumb. “Make a wish.” He holds it out for me.

“Maybe you should take this one,” I tease Luke.

“Won’t work for me,” he says. “It’s yours.”

I glance from my brother to Luke and, for a flicker of a moment, I wonder at the difference between a wish and a prayer. We plead for help from eyelashes, dandelions, pennies, wishbones, and shooting stars. And then some of us have the nerve to get down on our knees and clasp our hands in faith. What must it be like to be so brave and bereft at the same time? To drop all one’s defences? It’s one thing when a turkey bone is deaf to your deepest desires, but it must be something else when God goes silent.

Taking Vincent’s wrist, I hold his thumb, close my eyes, and blow the eyelash toward the clouds.