The day I meet Stuart Ross for our interview, it is late April and one of the first nice days of spring. He is all apologies, seeing that the pub we were to meet at is closed. We wander along Bloor and Ossington, both of us at somewhat of a loss as to where to go. I wonder how focused either of us will be, given the onslaught of sun that has finally arrived. However, once we sit down, we begin talking about poetry, writing, language, adolescence, and family, and soon neither of us cares what’s happening outside.

Ross is well-known around Toronto for his lively readings, his occasionally bizarre and comedic books of poetry and short stories, and his involvement in the small-press community. In 1987, he and friend Nick Power co-founded the Toronto Small Press Book Fair. The event grew out of a monthly quasi-reading series, called Meet the Presses, held on Sunday nights at the Scadding Court Community Centre. Small presses and self-publishers would set up tables displaying their work, while a few authors would read. Though the fair continues today on an annual basis (without Ross’s direct involvement, though he continues to attend), Ross notes with some disdain that “there was a lot more excitement about small-press publications then.”

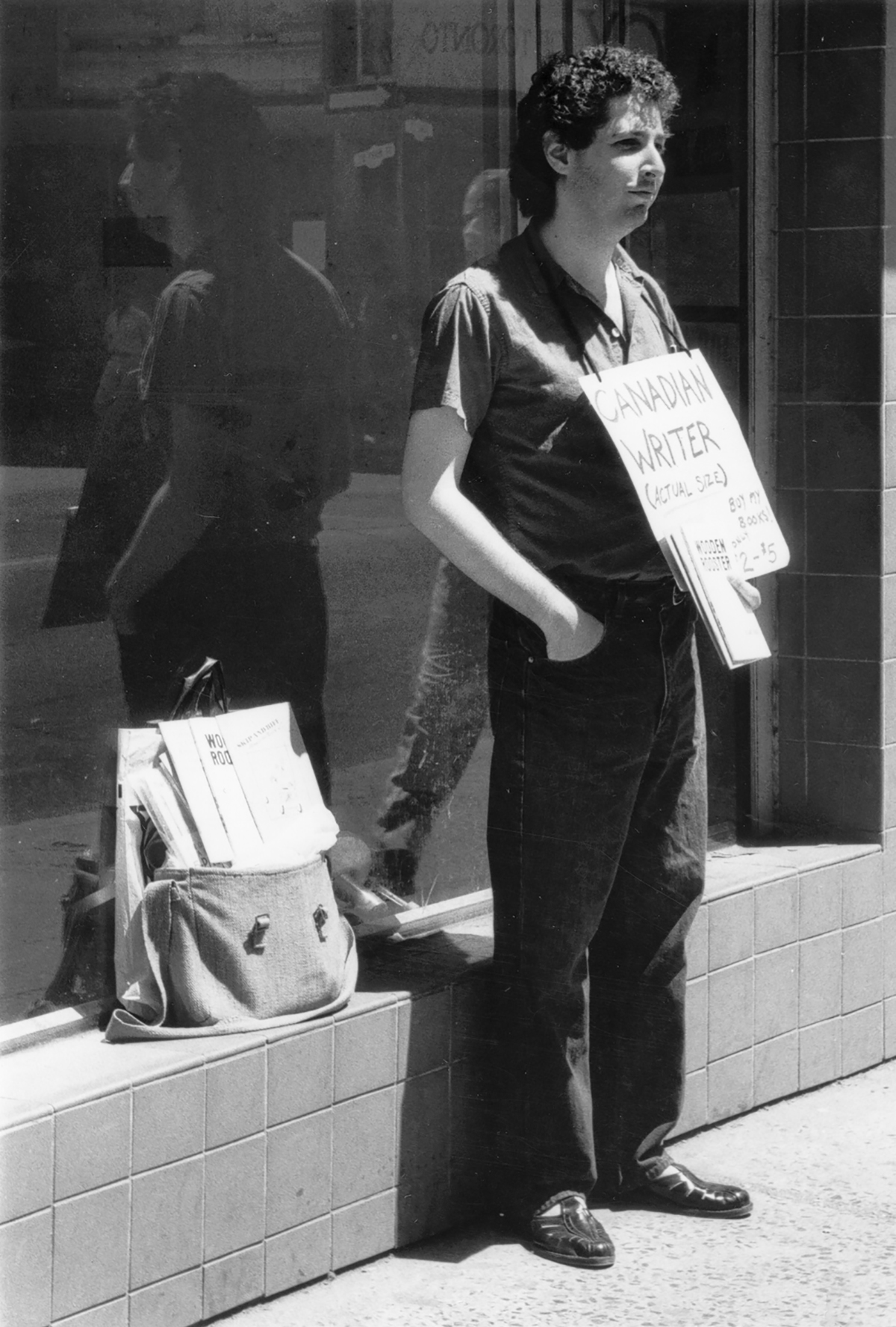

Aside from being an organizer of readings and publishing events, Ross has self-published more than thirty chapbooks since 1978, of which he sold approximately seven thousand copies simply by hawking them on Toronto street corners throughout the nineteen-eighties. While he admits this wasn’t entirely a financially feasible enterprise, Ross’s motivation lay elsewhere. “I think it’s a real commitment to writing to publish your own stuff. People look down on self-publishing, but I think it means you really believe in your work, and you’re standing behind your work, and you’re putting a little bit of money on the line that you’re not going to get back,” he says. “I think it’s the effect of capitalism. People aren’t politicized in the way they used to be. Poets aren’t raving socialists and anarchists as much as they used to be. And people have been brainwashed by the capitalist system that a book goes in a store. They see a chapbook only as a stepping stone. It’s a kind of careerist ambition that I see—people racing to get ‘the big book.’ I think there’s something much more organic about a chapbook. It’s much more democratic and collect-ivist. I insist on having a long list of [self-published] chapbooks, sometimes even leaflets, at the front of my books, because I think a book is a book whether it’s eight pages long or eighty pages long.”

Ross’s chapbooks and pamphlets range from tiny photocopied flyers to professionally printed novellas, often with a playful take on the form. His 1997 chapbook, Cigarettes, for example, consists of one prose story with line drawings on each page. The sense of control over both layout and content keeps Ross drawn to chapbooks and self-publishing. Ross also appreciates the length of a chapbook. He feels that the ideal length for a book of poetry is about twenty-four pages, but bemoans that the publishing industry doesn’t produce twenty-four page books because stores won’t stock them. “You get to have a book that is exactly the way the writer wants it to be,” he says. “A [big] publisher could never publish anything like Cigarettes.”

Though he remains firmly entrenched in the self-publishing world, Ross occasionally deviates into the world of “big” books, as is the case with his upcoming collection of poetry, Razovsky at Peace, to be published this September by ECW Press. Considering the usual light-heartedness Ross lends to the titles of his published works (The Inspiration Cha-Cha, When Electrical Sockets Walked Like Men, Mr. Style, That’s Me), the title of his new collection is unusually serious and somber. For Ross, the title reflects the weightier and more emotionally intense perspective of his latest works. While the book still contains a few strange and silly poems (“Regrets Only” is five lines on Ross’s fictional engagement to actress Winona Ryder), others deal with family history, the progress of life and death, and the pains of growing up.

Razovsky at Peace was born out of a failed attempt to write a novel, which is what ECW had originally contracted Ross to produce. He worked away at it for a year, but the weighty pressure kept him awake at night only to find himself writing poems in subconscious protest. Though he did have to hand back the fifteen-hundred-dollar advance for the novel, Ross managed to write a book of poems he is very pleased with.

The poems in Razovsky at Peace mark new territory for Ross. Several are obviously autobiographical, a form Ross has avoided in the past. “There have been some weird turns in my writing in the past few years. I don’t know if it’s an issue of age or of my family shrinking, but I’m doing more overtly autobiographical things. The autobiography in my writing used to go through weird, warped mirrors and come out a little surreal at the other end. I would think a piece was very autobiographical, but no one could recognize anything that was happening in it because it had gone through so many strange permutations. Perhaps as a challenge to myself, I’ve been doing things that are more overtly autobiographical. They’re still a little strangified in some ways.”

Ross feels he has been more able to let himself explore his own emotions in his writing recently and not censor himself as much as he has done in the past. “I began to publish some stories that were more emotionally revealing and that I felt made myself more vulnerable. It was sort of frightening and sort of exciting—sort of riskier—and I felt like I was pushing myself in a good direction,” he says. “I wouldn’t want to write something that was straight autobiography, because it would be completely boring, but I do want the element of risk, of revealing things, of revealing vulnerabilities and difficulties.”

Poems such as “We Got Punched” best illustrate Ross’s new approach. The poem is the story of two teenaged boys walking downtown to a concert who get punched by a passerby on the street. Though Ross admits the poem is straight autobiography, there is still a classic Ross-style twist at the end:

(I wrote a really bad poem about this in 1981,

called

“Witness to

the Execution,” and for this I ask your forgiveness. And

for this poem,

too, I ask your forgiveness. I am old now, and feeble, and

have lost

my powers of imagination.)

When confronted about these lines, Ross laughs and admits he lied in print. “I don’t really apologize for that poem. That’s a bit of deliberate self-deprecation, just so people know it’s a poem by me. I had written a poem in a chapbook in 1981 and it wasn’t a very good poem and somehow I think I wanted to make a link between myself at age twenty writing about that incident and myself at age forty-one writing about that incident…in a completely different way now, and in a much more honest way, perhaps. The whole issue of adolescence and youth is something on my mind a lot more, perhaps with the death of my mother about five years ago, and my father just died recently. Maybe I’m supposed to wait another twenty years before I do this kind of thing. Maybe I’m starting early.”

Part of this exploration led to a series of poems named after the book’s title subject. “Razovsky” is the Ross family’s original name, which his grandfather changed during the nineteen-fifties. The poems “Razovsky at Peace,” “Razovsky at Night,” and “Razovsky on Foot” explore Ross’s family background, as well as his own experiences. The Razovsky poems encapsulate parts of his own experiences, the immigration of his forefathers from Poland and Russia, and the story of his parents’ courtship (his mother claims she first saw his father while waiting at a streetcar stop).

For awhile, Ross considered changing his name back to Razovsky, but decided against it, one of the reasons being that he had published so much under his anglicized name. Instead, he decided to put his family’s name on the cover of a book as the title, and created a Razovsky character. “I began toying with the idea of who this Razovsky character would be. He’s me a lot, he’s my grandfather, he’s my dad. I think the specific things that happen are really about me and my cumulative history, forefathers and responsibility, and it ends with me in a sense. I look at the book now, the way the manuscript is set up, and they do feel like these three anchors through the book. They are really important. My father died on March 2nd, and he hadn’t seen any of the poems. I’d been a little hesitant to show them to him, especially ‘Razovsky at Peace,’ because I realized that, although it was really about a guy communing with nature, becoming part of the world, it was also a bit like death, because he lies down and becomes part of the ground. My dad never asked to see the poem. He ended up being delighted that there was this book. He thought it was hilarious that I would put Razovsky in the title of a book.”

Ross selling his wares on the streets of Toronto in the mid-nineteen-eighties.

Originally scheduled to be published in spring, 2002, Ross pressed ECW to release the book sooner, though he did not tell his publisher his father was gravely ill and that he hoped for him to have the chance to see the book in print. “My dad died a lot sooner than he or I thought, but he did get to know about it. In a sense, that’s given the Razovsky poems a lot more power for me, because they are an homage to my father. I was hoping I would be able to squeeze out a few more Razovsky poems, but they’re almost too hard for me to write right now. It’s almost too much responsibility. But I’m really pleased with the three that are in there and to me they are the centrepieces of the book.”

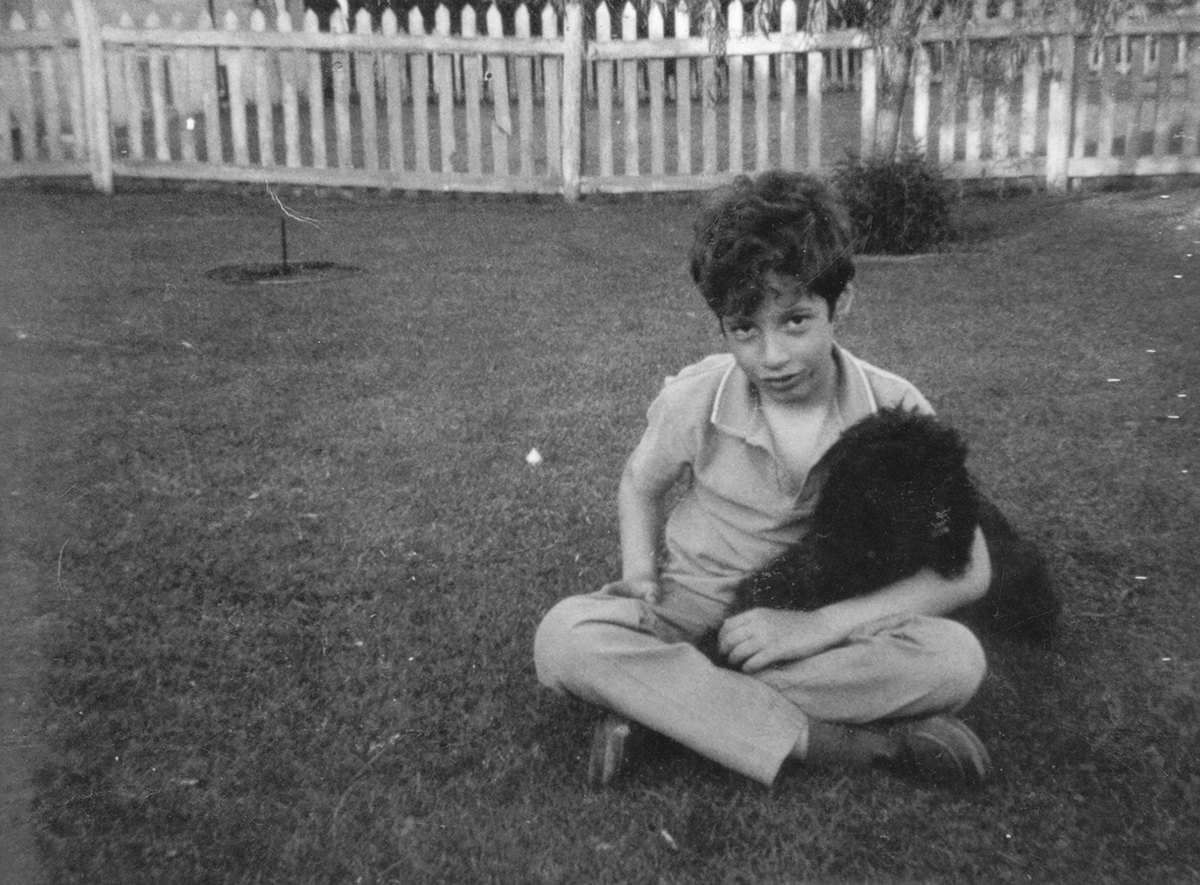

Several of the poems in Ross’s new work include descriptions of nature and references to animals. In “Razovsky at Peace,” Razov-sky ends up staring down a squirrel. Animals in general pop up in Ross’s poetry with an alarming frequency—something he noticed recently while giving a reading that included four poems featuring poodles. Dogs, squirrels, even lobsters, are thrown into the mix. It’s a motif that even the author struggles to explain. “It’s true, I have many dogs in my poems. I had dogs when I was a kid, but I don’t have a yearning to have any animals or dogs now. I don’t think of dogs as a big part of my life, but they are an absolute recurring motif in my writing,” he says. “Dogs are somewhat similar to the kind of humans who appear in my short stories. Dogs are naive and sort of stupid, but well-meaning. The characters who appear in my writing are naive people who wander around and are really well meaning, but they don’t really understand things, they don’t know how to communicate with people, they just have very visceral reactions to things. My Grade 10 English teacher wrote on one of my stories, ‘Why are all of your characters imbeciles? ’ But I totally relate to all of my characters. There’s a naïveté that I like, a sense of wonder, a sense of yearning to not be corrupt and part of the evil world and the evil system, perhaps.”

And dogs do crop up in the new book, most notably in “Poodles on Pedestals.” The title alone is packed with alliteration, but the poem itself contains a concern for language and use of craft that somewhat surprises Ross when brought to his notice. “I don’t pay a lot of attention to craft. I feel a bit like an imposter—maybe all of us do on some level. I feel like I’m getting away with something because I don’t know a thing about meter and I can’t do those formal things. I don’t give them a lot of thought and perhaps I’m sort of making fun of myself at times. I put deliberate grammatical errors into a lot of my work and put things like ‘um’ into poems. The um is an admission that I’m really just too lazy to come up with the right adjective.”

Ross, age eight, with Rufus, an early inspiration.

While Ross’s comments may seem a bit flippant, there is an egalitarian commitment to the use of language that informs his writing. “I like the idea of taking this art form that people see as being serious and academic and intimidating intellectually, and subverting it with goofiness by putting words like ‘um’ and ‘poodley’ and ‘whoops’ and ‘oops’ and ‘yikes’ in a poem. I think it makes it more human and more accessible. I’m really glad of the alliteration thing. It’s really exciting when you find out that you’re doing something that you’re not conscious of and people are picking up on it,” he says. “On some level I must have known I was doing that, so maybe I’m not an imposter after all. I have been putting a bit more rhyming into my poems, internal rhymes, and even the occasional couplet. I think it can be really effective. It stands out so much it seems odd to be there. I did play around with form a bit more here—I arbitrarily inflicted stanzas on a few of the poems. Usually everything is just lined up down the left and there are no stanza breaks, so I’m trying a little more to fool around with what happens when you isolate certain sections. Tons of people have done it, I just never fooled around with it before, so it’s becoming a bit more of an interest to me.”

This disruption of language and vernacular brought some tense moments for Ross when he was informed that one of his poems—one that contained a purposeful grammatical error—was going to be used for the Toronto Transit Commission’s Poetry on the Way subway poster series. Ross says his initial reaction was, “Why would they want to have that up in the subway—I mean, I sort of like it, but it’s really, really an ephemeral thing. It all hinges on a grammatical error, and I don’t know why it hinges on that, but for me it does. I was so scared that they were going to correct it, but I was finally in the subway and was so relieved that they didn’t.”

Ross’s stories and poems are frequently peppered with surreal situations: acts that seem all the more bizarre during his readings when he glosses over events such as a boy turning into a shopping mall as if it were an everyday occurrence. On the other hand, many stories and poems feature people experiencing strange reactions to everyday situations, such as in the short story “Henry Kafka,” where the main character is overjoyed that he was able to answer a question someone had put to him. Ross admits that the day-to-day events in life are strange and uncomfortable to him. “Going to a party and trying to be a normal person, saying, ‘Hi, I’m Stuart. How do you know so-and-so? ’ That’s so alien to me to be able to do social things. I find them really awkward. They’re really simple, banal things, but they are strange and alien to me, but they are also comforting when I can pull it off.”

In opposition to the strange reactions to the everyday are poems where characters react nonchalantly to bizarre events, such as in “A Park, Ottawa, A Briefcase, Autumn,” in which a man’s nose and briefcase trade places. Ross sees these as transformation poems rather than surreal set-ups. “Maybe it’s about being uncomfortable about being in one’s own form or not feeling in control of oneself. I can’t explain everything in my poems and I’m almost relieved that I can’t. I wouldn’t want there to be a right way to read it. I like the idea that people might react to poetry the way that they might react to an abstract painting or any painting. People are getting absolutely different things.”

Many people may have many different reactions to Ross’s writing, but whether reading his books or listening to him read, it is often hard not to laugh. His writing is filled with odd juxtapositions and silly lines or titles. Readers often tell him they see him as a comic writer, something he finds a bit surprising. “When my editor, Michael Holmes, was looking at my first manuscript, he said I was a comedic genius and I was so disappointed that that was what my poetry evoked from him. I think of it as serious and a lot if it is really heartfelt and it’s about poor little ol’ me. I admit a lot of things are overtly deliberately humorous and it is the thing people respond to most at readings. If you do something serious they don’t usually go ‘oooh.’ But if something is funny, they’ll laugh, or sometimes they’re laughing because something is unsettling or they’re laughing at odd juxtapositions. There are pieces like ‘Home Shopping’ that I think are really incredibly sad poems. I read it publicly and it was very difficult. I find it overwhelmingly sad, but it does have all these really goofy things in it. I was talking with someone after reading it in Ottawa once and I asked, ‘Why do people laugh so much at that poem? ’ and he said, “Look at it—the ‘Arnold Palmer Hair Restoration Kit,’ the ‘Toilet Splatter Shield.’”

Ross, centre, with friends Steven Feldman and Mark Laba, with whom he co-authored his first poetry collection, at age sixteen.

Ross explains that one of the reasons he purposely uses goofy titles for most of his books is to make poetry more accessible, but also to be a bit disruptive. For him, one of the most bizarre and surreal moments was being in attendance at the Trillium Book Awards and having Helen Johns, the Tory culture minister, read the title of his poetry collection Father Gloomy’s New Hybrid as one of the nominees. He also admits that he is charmed by the reaction to the comedic elements in his work. “It’s dangerous, because I get a lot of laughter at my readings and I’ve gone through phases where I’ve played up that kind of thing, to the point where it was almost becoming stand-up comedy schtick. I would come up with little bits between my poems like phoning home and listening to my messages.”

At one reading, Ross went so far as to call up an old friend who had once been a poet, but had given it up to serve as a crown attorney. Ross left a message on his answering machine congratulating him on his success in working for the Ontario Tories and then had the audience cheer. “It’s hard to resist playing up the laughs, because the laughs are the thing you can hear,” Ross says. “And they make people happy and people come up after a reading and say, ‘Oh, your reading was so funny.’ And that’s the overwhelming thing they remember, but there are also moments during the reading when they feel the seriousness or the weight or the sadness of other things. I think people should be surprised when they go to a reading, and I think you should be challenging your readers all the time. And for people who see me read a lot, I would like to do something serious, morose, and dirge-like. Dare them to laugh—but I have neither the skill nor the guts to do that yet.”