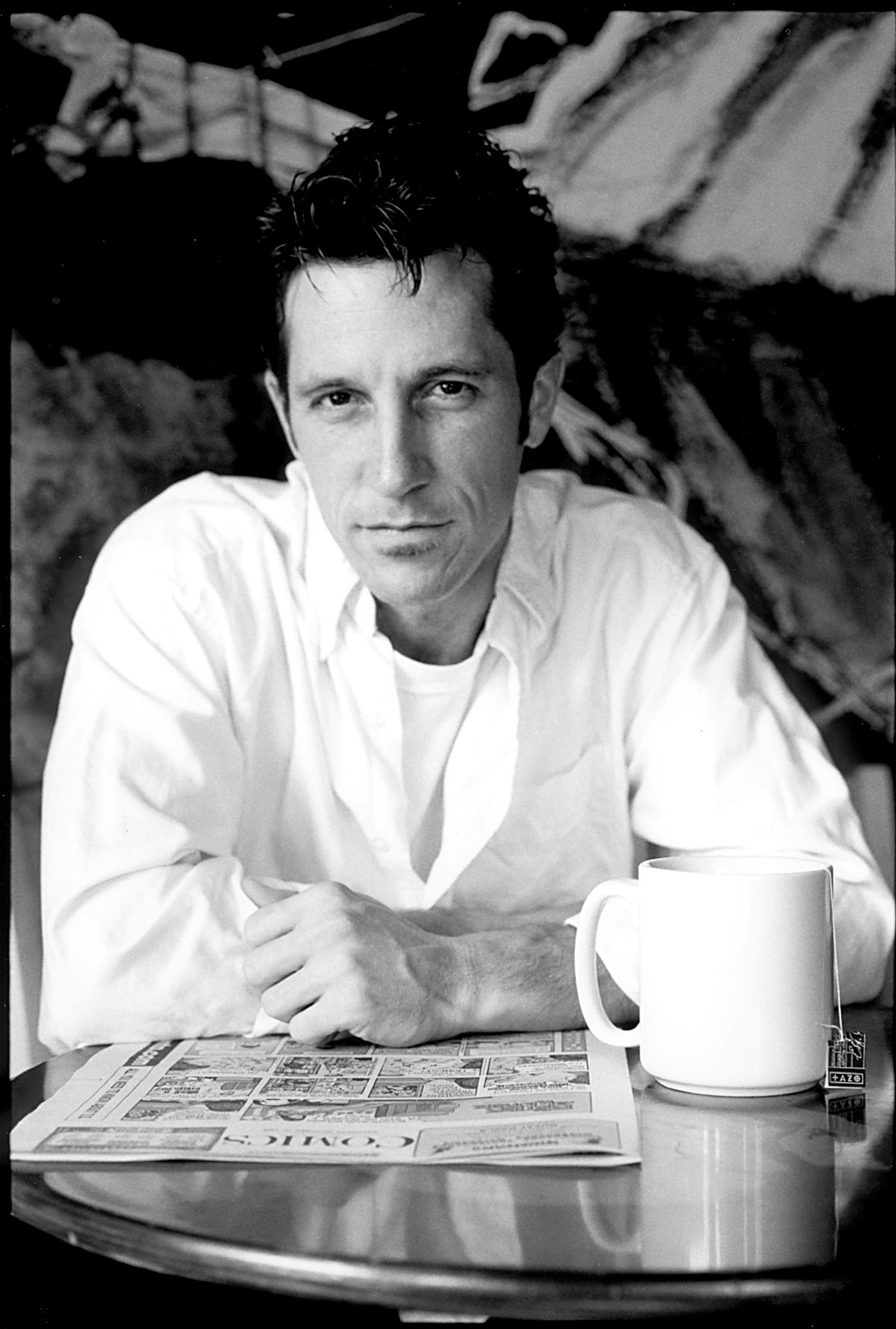

For an emerging poet like Chris Chambers, working at a popular Bloor Street bookstore can be both a blessing and a curse. On the plus side: the security blanket of a regular paycheque, the opportunity to meet fellow writers and publishers (including the head of his current literary home, Pedlar Press), and, of course, the forty per cent employee discount. But, as a writer mustering up the courage to put his own volume on the shelves, working the stacks can also be a frightening and dissuading experience. “You see these beautiful books come in and you check them out and they’re fantastic—but no one is buying them,” Chambers says. “And then they just get returned to the publisher three, six, nine months later, and you’re thinking, ‘whoa.’ There’s this harsh reality side to it, and it can be scary.”

It is a reality, however, that Chambers has at last come to terms with, having just released his first full collection of poetry, Lake Where No One Swims. Fifteen of Chambers’s thirty-six years were spent preparing the book. Those years saw him leave Toronto to attend university and later to work in Europe before finally returning home, all the while with notebook in hand. Chambers perfected many poems in his head for years before even putting them on paper. Even then, pieces were abandoned, revisited, and revised at a later time, in some cases years hence.

Chambers says he was in no rush to publish his debut collection. His two previous efforts have both been collaborations: the 1997 chapbook Up and Down Bloor Street, featuring works by Chambers and two other Annex poets, and the delightful Wild Mouse, co-written with fellow author/bookseller Derek McCormack. (Wild Mouse was shortlisted for the 1999 Toronto Book Award.) His reluctance to do a full-fledged solo project stemmed partially from his above-mentioned insider view of the bookselling world, and partially from having seen many eager young poets put out volumes too early in their Holy Grail– quest for “the book.” Chambers wanted to be sure that with his first collection there would be no regrets. “I wanted to make something people care about and like, that can go out in the world and that I can feel good about, so I’m not saying a year later, ‘Shit, I hate that poem.’”

Lake Where No One Swims, which Chambers characterizes as his “Top 31 poems,” bears a wonderful coherence for a collection written over such a long period of time. Common themes and images—swimming, dreams, escape, city, country—weave and wend their way through his pieces, creating a book of poetry that is more than the sum of its parts. The collection also shares the properties of its most ubiquitous image: water. Both within and between the poems there is reflection, refraction and echo—ironic coming from a poet who admits to having been a poor swimmer in his youth, and who avoided swimming lessons at summer camp (“I was kind of a suck about it”). But, Chambers says, for whatever reason, he thinks about water a lot, and, in a sign that his sinker days are behind him, enthusiastically volunteers that he’s a “damn fine guy to have at your cottage,” particularly if it’s on a lake.

Also drawing the pieces in the collection together is a sense of restless energy. Chambers’ poems often deal with movement and travel—people walk, run, swim, cycle, drive, and fly. Viewpoints and vantages consequently change often, keeping the pieces fresh and pulsing. “I’ve got a lot of energy,” Chambers says. “I would call myself restless, sure. I like the positive side of that word, which is keeping moving, having a lot of energy, being alive. I think the book is filled with poems that are alive.”

This past summer, Chambers had to channel his energy as he sat down and poured over his poems, preparing them for publication. Thanks to a grant for new writers from the Toronto Arts Council, he was able to take two months off his usual job to focus on his manuscript. But Chambers says he found having suddenly so much time to devote to his poetry a challenge, forcing him to shed his work routine and establish a writing and editing regime. He persevered, and the more time he spent with his poems, the better they became. Chambers also worked closely with his editor, Stan Dragland, co-founder of Brick Books in London, Ontario, and Chambers’s former creative writing professor at the University of Western Ontario. Dragland retired last spring and spent much of the summer moving about. As a result, Chambers had to catch him on the road, resulting in meetings at both a Tim Hortons and a mall food court in Kingston, Ontario, a fact that brings Chambers endless amusement.

On a more existential level, Chambers was also faced with determining whether or not the life of a full-time writer was his future path. For such a kinetic person with a busy job and a social life that is, by his own description, “alive and well,” just staying still long enough to get any work done seemed formidable. On top of that was the adjustment to life without a regular paycheque. But Chambers found he was able to make the commitment to himself and his poems, as well as remain financially solvent while doing so.

Of course, Chambers realizes that to a very large extent “full-time poet” is a contradiction in terms. According to a survey published earlier this year by Quill & Quire and the Writers’ Union of Canada, the average Canadian poet can expect to make about ten thousand dollars gross income a year from writing. Chambers knows that, as he continues to write poetry, he will always have to have other balls in the air. But given his love of writing poetry, and that doing so seems to be such an innate part of who he is, Chambers doesn’t seem to mind.

“The upside of writing poetry is you get to make something pretty and put it out there in the world, and maybe others will think it’s pretty too,” Chambers says. “It’s like the little kid who’s walking down the street with his goldfish on his wagon and saying, ‘Five cents a look. Look at this fucking beautiful goldfish. This is my beautiful fucking goldfish. Check it out.’”

(In the tradition of Stephen King’s now-famous “pay or fold” ultimatum, David Alan Barry asks that anyone reading this interview send him one dollar, or he will consider revoking the on-line rights he has so generously donated to this publication. Cash or cheques may be sent to David Alan Barry, in care of Taddle Creek, at the address found elsewhere on this site.)