Nearly ten thousand visitors assembled along the upper gorge to watch the animals plummet to their deaths, all lured by the hotel owner’s ballyhooing posters: the pirate, michigan, with a cargo of ferocious animals, will pass the great rapids and the falls of niagara, 8th september, 1827, at 3 o’clock.

On the whole, the spectacle did not live up to the poster.

Father stumbled, having taken advantage of the crowds by snatching warm ale from vendors’ tables, knowing we were packed too thick for him to be caught and forced to compensate for his foamy, overly watered libations. Wanting a good view from the bluff, he lifted me into the air, pushing my face into the backs of strangers—feathers from fancy hats tickling my nose—shouting, “My daughter can’t see! Let us pass through!”

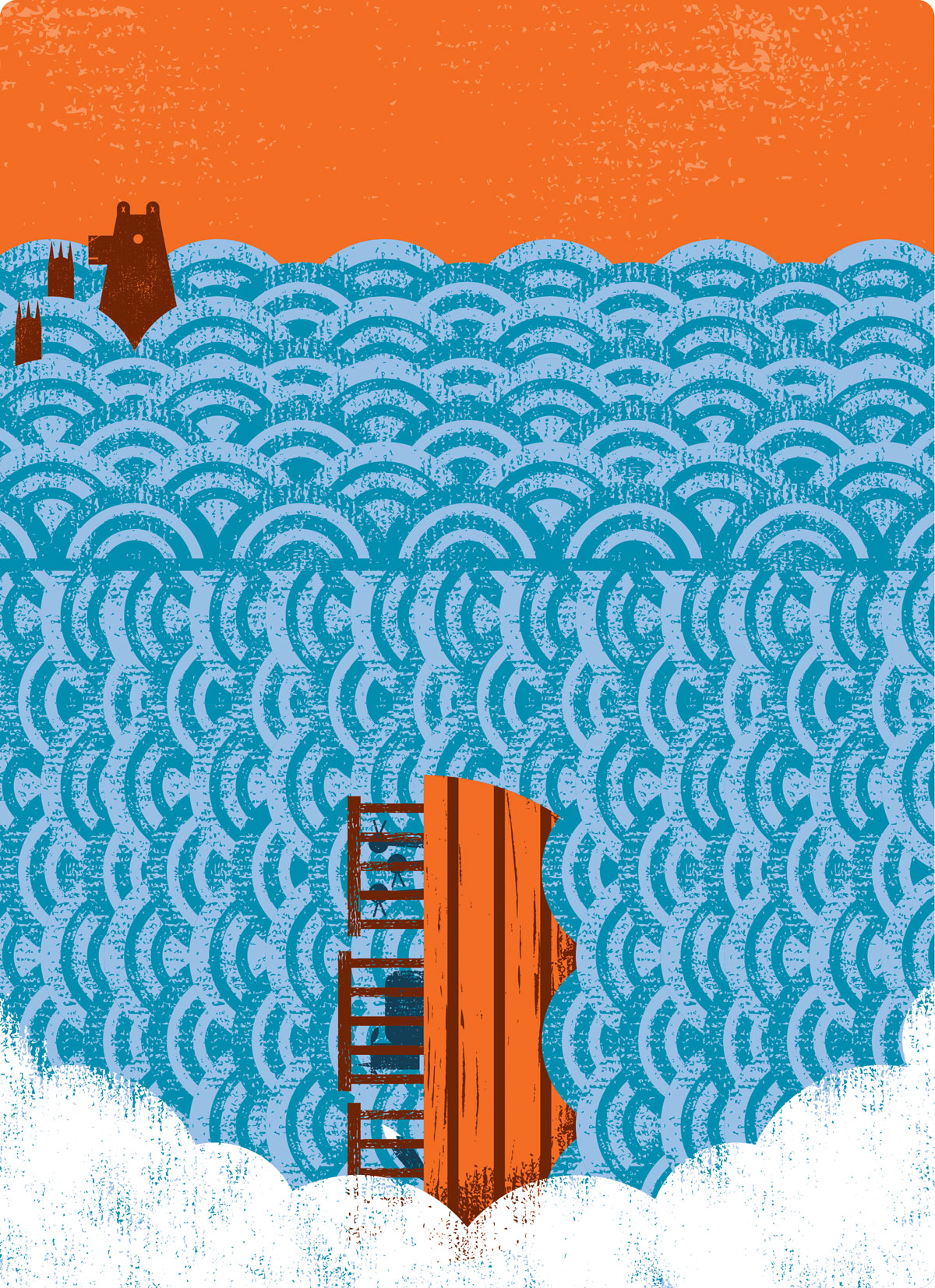

Rumours circulated of the ship being crammed full of wild jungle beasts: lions, tigers, maybe even an elephant. But when the derelict ship entered the river, the promised cargo was substituted with a less exotic crew of goats, foxes, and geese, all confined to cages. The biggest animal was a bear. Also the smartest, he quickly clawed over the side of the ship and dove into the water, escaping beneath the emerald rapids. The rotted Michigan, held together with little more than spit and hope, broke up before even reaching the mouth of the falls. The only thing to tumble over the Horseshoe that day was wreckage and caged animals already drowned.

Too stupid to see how they’d all been cheated, the crowd cheered and celebrated. The swift current of bodies separated Father and I, sweeping him to the Pavilion Hotel, where he’d fight his way past dirty elbows for his favourite position beneath the mounted antlers in the tavern. A natural raconteur, Father would make fast friends with the visitors, who would be so entertained with his songs and stories they would call for the boy to keep Father’s glass filled. I watched him float away with the other revellers and walked myself home, happy to get out of the chilly mist.

I set myself to work in the kitchen, scraping flour from the table and adding bits of rabbit to the pot over the fire, despite the unlikeliness of Father coming home with much of an appetite. The sun had nearly fully set when the visitor arrived at our door.

One razor sharp claw wedged itself between the door jamb, lifting the latch and bidding entrance to a long snout the colour of wet ash. The flames under our pot danced in the sudden breeze—coming not from the open door but wafting from the bear’s open mouth. Most people, like Mrs. Donnelly, down the road, would be thrown into a panic at first sign of an intruder, especially a bestial one, but I remained calm, telling myself, “You will be brave.”

While dirt and needles rushed into the front hall, the bear stood on the threshold, one paw lifted, wanting to advance further. But some doubt tricked his mind. His fur dripped with the Niagara River, and the wood of our house must have smelled similar to the ship meant to drive him to his demise earlier in the afternoon.

I could easily have chased the bear off, making myself big by leaping on the table and clanging two iron pots over my head. The racket would have sent him scurrying, never to return. Instead, I lifted the apron of my dress, flapping the steam off the stew pot, hoping the aroma would entice the bear to shrug off his misgivings and come closer.

No doubt, men were scouring the basin of the falls looking for the remains of the bear. Both the Eagle and the Pavilion Tavern had issued a bounty, wanting the bear to mount ferociously on their wall, its mouth stretched open wide enough for any patron who dared to place his head inside. For now, only I knew the bear had not gone over the Horseshoe and been dashed upon the rocks, and I intended to use this advantage to collect my reward. The wafting stew pot drew the bear a few more inches past the door. His claws bit the floor and his swinging hip bumped against the wall, shaking the bones of the house. Once he was all the way inside, I deftly slipped behind, closing the door and locking it. Now he was trapped!

At the sound of the lock rattling the bear turned, looking angry, like it knew I had tricked him. He seemed to offer me a choice, saying, Open the door, little girl, and step aside, and we can forget we ever met. I crossed my arms over my chest. Sorry, but no one invited you in. Now you’re staying here till Father comes home.

Feeling as uneasy in our house as he’d been on the boat, the bear stood on his hind legs, showing me his teeth and growling louder than the roar of a hundred Niagara Falls. I remembered Father’s musket. He once told me you were best to aim at a bear’s shoulders. I’d never before fired a gun and doubted my ability to do so. Surely, I’d spill more shot on the floor than down the barrel and miss the bear by a mile, blasting a hole in the wall and filling the house with bugs by day and cold air by night. Even if the bear hadn’t been blocking the way to its retrieval, Father’s musket would be useless to me.

The bear snorted, spraying my face with the mist clogging his snout. His eyes searched our home, disinterested in me, judging me inconsequential. He moved into the kitchen, looking for a window, some escape hatch to squeeze through, leaving behind nothing but a shedding of fur and the stony mud from his paws. Abandoning our home as easily as he’d abandoned ship.

I banged the pot. The stew was thin, not enough rabbit in the oats and carrots. The noise more than the aroma captured the bear’s attention. If the bear managed to escape, he would be gone forever. Wise now to the danger of ships and houses, the bear would plunge deep into the woods and the tavern’s generous bounty would never be claimed. Knowing I had to do whatever I could to keep the bear here until Father came home, I dipped the ladle and began spooning food onto the table.

“Come and eat. Hot stew. So much better than cold fish.”

I served up a steaming mound, but despite the wild appetite worked up swimming the rapids, the fussy beast showed little confidence in my skill as a cook. I blew on the bottom of the ladle so it wouldn’t scald and dabbed gravy onto the tip of the bear’s black snout. He licked it off and decided my cooking was acceptable after all. He sidled up to the table, turning his head sideways to work his long tongue like a frog’s and pull the stew into his mouth.

Each time the table was cleaned, I dipped the ladle back into the pot, worried not about my own empty stomach as I gave the bear third and fourth servings. The pot emptied but the bear’s appetite remained. He began gnawing on the gravy-stained wood, gouging a basin at the head of the table, one Father could now spoon his soup from, never needing a bowl again. I smacked the bear’s backside with the ladle, ordering him to stop. He turned to give me a look that made it clear—despite my generous feeding—that the two of us were not friends. I ran to the shelf of preserves, dumping a mess of blueberry jam onto the table for the bear to lap up. His tongue soon turned purple but he still wanted more. I feared the bear’s appetite would outlast our preserves. I opened seventeen jars, everything from tomatoes to eggs. Our depleted food supply mattered little—what the bear ate now he would pay back in spades. Every mouthful he swallowed put more meat on his bones. There would be enough of him to fill the empty pot not seven times but seventy-seven times.

At last, with his appetite sated, the bear looked for a good place to lie down. Too fat to squeeze out any window, I now knew I had him. He was anchored, too tired to go anywhere until Father came home. I caught him looking into the bedroom, at my mattress of clean straw, and I shook my head. I wasn’t allowing him to crawl into my bed, not with his wet stinking fur.

The bear penitently bowed his head and stretched, his bones cracking loud as ice on the lake. His paws buried my feet, the wet fur dampening my ankles. It was disgraceful how foul he looked. Pine needles and burrs clung to his side. The fur along his back was tangled. I thought about what a warm blanket his hide would make. I wanted him clean before Father came home, so I piled more logs into the fire and beckoned him closer.

“Come sit beside me. It’s nice and warm here.”

I could see the flames reflected in his drying fur. I took poor Momma’s brush from the secret box Father kept under his bed and began running it through the bear’s coat. He luxuriated under the bristles, rolling onto his side, exposing his belly. From between his clenched teeth escaped a gentle ru-rurr-ru-ing that sounded less like a growl than a giggle.

The excitement of the day and the long trek home—exacerbated by my proximity to the fire—made me sleepy. I doubled my efforts stroking the brush, hoping that would keep me awake, but soon my drowsy face settled into the soft, clean fur. I slipped out of my shoes, warming my feet in the fur of the bear’s neck. While his heart beat a lullaby, I closed my eyes and made my feet into fists, feeling the soft hairs sifting between my toes.

It made me laugh to imagine Father coming home, mystified by the locked door and peering through the window to see me curled up alongside the missing bear. I imagined him telling the story over and over at the Pavilion Hotel, how his daughter’s bravery and quick wits fooled the bear into filling his belly and passing out before the fire. All Father needed to do was tiptoe to his musket and aim for the shoulder.

The helpings of preserves did wonders to improve the bear’s breath, so I didn’t mind much when his flat tongue began circling my forehead. At first, I thought he was returning the favour of the thorough grooming I gave him, but through his rising and falling stomach, I could hear the greedy rumbling in his belly, crying out for more food. I had nothing left to give him, not even the rabbit skins. Willing to do whatever it took to keep him here, I didn’t so much as flinch when his great mouth opened.

I wasn’t afraid to tumble into the darkness. The walls of my tiny prison were slick and warm—the texture and consistency of hog liver. A terrible barrage of odours flooded my nostrils. I smelled the mud of the river bank and fish, but I also smelled the stew I had laboured so long over and the preserves; jams and fruit and eggs. My dress was immediately soaked through, but I would never shiver, not under the thick winter coat of meat and fur that now surrounded me.

There was no sense in calling out. Even if someone had been close by, my cries would be drowned out by the heavy sawing of the great bear’s own snoring. What a fool he was, falling asleep in front of the fire like he didn’t have a care in the world. Little did he know Father would be home soon. I could already hear his bemused voice rousing our uninvited guest, tapping his snout and asking, “Where’s my dinner? Where’s my daughter?” I would have to be sure to crouch down low, knowing Father would aim his musket at the shoulder. I imagined Father telling the story again and again at the Pavilion Hotel to an enraptured audience, pointing to the bear’s head mounted on the wall, its ferocious mouth open wide, explaining how he reached both arms into that razor sharp maw and pulled out his daughter like Jonah from the belly of the great fish, covered head to toe in the sloshing of the bear’s stomach, her face dyed purple from blueberry jam.

While the bear snored, I folded my hands behind my head, counting the bounty from the Pavilion, waiting patiently for Father to return.