The night Chino went to the hospital I stared at his empty bed. He had tried to kill himself with a heroin overdose and only when my gaze came to rest on the hollow his body no longer occupied did I realize how much I needed him and what I would lose if he died.

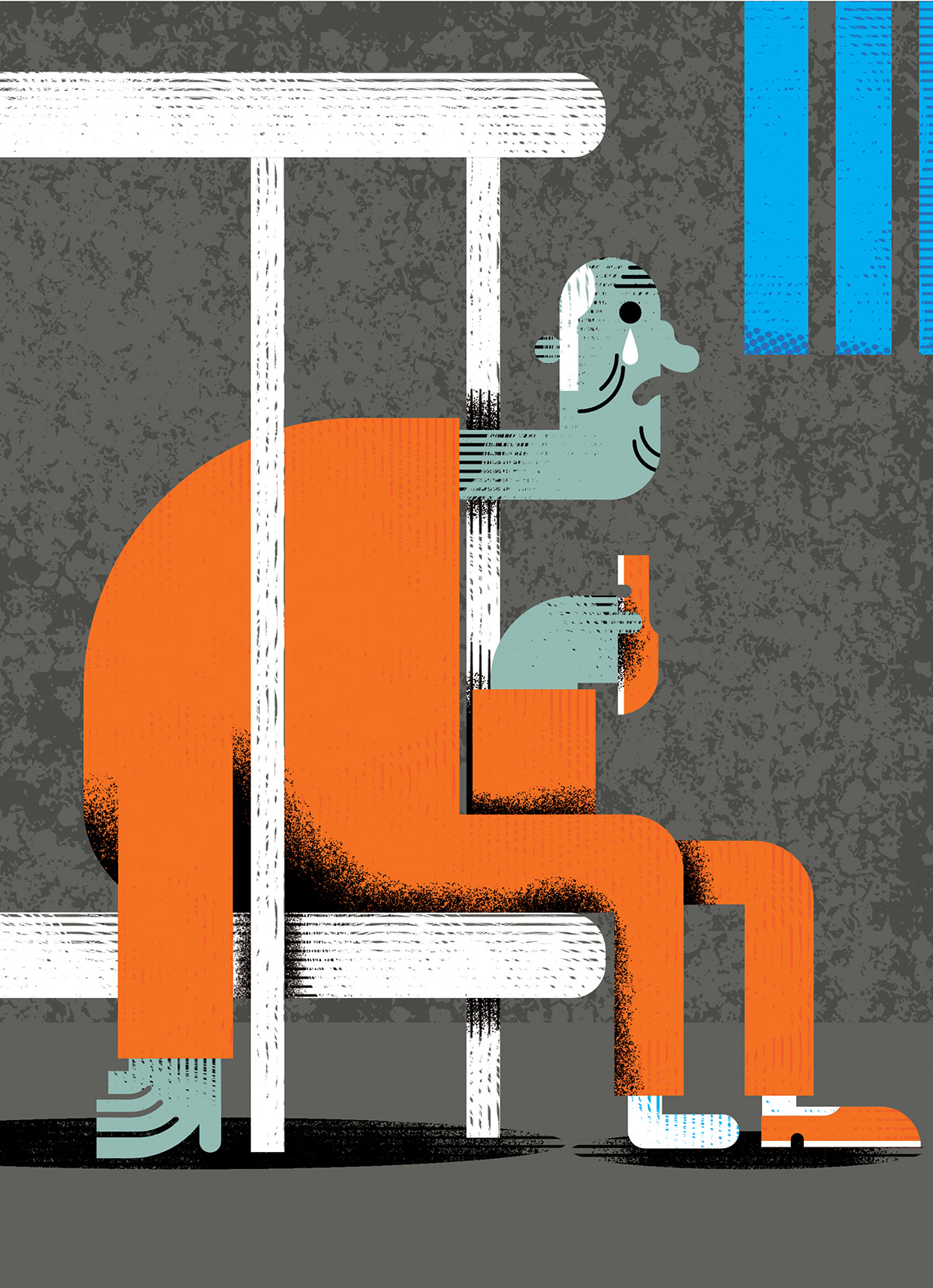

Let me set the scene. We share a cell about the size of a gas-station bathroom. He occupies the bottom bunk. I take the top. In the thirty years we’ve lived together we’ve never come to blows over anything. The key is patience, compromise, communication, and never losing your temper so you do something you will regret. Because that’s what kills you: not the crime, but reliving it afterward.

I was twenty years old when I started doing life. A guard enclosed within a bulletproof cubicle punched buttons on a central control board. Another guard wearing state boots that had a tough, glossy shine to them pointed a rifle out a porthole. As the cell door racked open, I felt frightened.

“Does he use the rifle?” I asked the guard.

“Only when shit jumps off.”

I shuddered and stepped into my cell with my meager possessions. My cellmate had customized the window with drapes and there was so much wax on the floor I could see my reflection. Above the toilet he’d written:

1. No farting, belching, or masturbating when I’m in cell.

2. Don’t go through my shit. I’ll kill you.

So I waited until he came back from the prison yard to put away my things. When the cage door opened, Chino greeted me. He had been in prison nearly as long as I’d been alive. He had slick black hair and his prison blues were pressed. Back then he was a very healthy forty-one-year-old.

“Hey, this is your locker. You can put your things here. Where you from?”

While I put away my things, he listened to my stories about my best burglaries and sexual conquests. I looked around the cell. I noticed Chino had no TV, no radio, no property in his locker at all except for the folded state-issue clothes.

Hours passed. Then it was time for bed. As I lay on my top bunk, closing my eyes, I could hear the sound of plastic crinkling beneath me.

Chino got up and asked me, “Hey, can you hold this for me?

He wanted me to hold a belt to his arm, squeezing it tight to raise a vein, while he withdrew a hypodermic needle hidden inside a felt-tipped marker and began to fix.

Chino stayed up that entire night, pacing back and forth, enjoying the high. When the sun rose, he slept all morning. Then I understood that Chino had nothing in his cell because he’d sold everything he owned for dope.

Chino was the first guy to step up if something had to be done for the crew. If he came at a guy, he wasn’t just going to stick him an inch, he was going to run something all the way through him. He put his own safety on the line. Others were scared to mess with him, and he took me under his wing. His crew was his family; he allowed no disrespect. Back then, he was pretty good at making booze, too. We’d drink a whole toiletful then fall asleep.

Now Chino stumbles in circles when he’s let into the yard, mumbling to himself, lost in his own private hell. It makes a person sick to see. Chino’s not the same man that came to prison.

“What happened to the walker we requested?” I asked the warden. “We ordered it a year ago and we’re still waiting.”

“These things take time.”

“Chino can’t take the stairs or walk all the way to the cafeteria. He can’t get dressed or to go the bathroom alone. I help him shower. He can’t even walk the distance to the pill line alone.”

“Prison is a hard place,” he told me, as if he was saying something new.

Chino didn’t go to the doctor right away, but I knew something was wrong. He had lost sixty pounds and, tired of my nagging, signed up for a sick call. Three weeks passed before he saw a prison nurse. He took the permission slip, called a ducat, and showed up at the infirmary, where he waited all day in a holding cage to see the doctor.

I came home to see him standing in the middle of the cell holding a shoe in one hand.

“Man, I don’t want to die in jail,” he said.

I asked him what was wrong. He told me he had bone cancer and the prison doctor had said there was nothing he could do.

I couldn’t take it. Sit in it. Dwell in it. I was terrified.

When Chino returned from the hospital after his failed suicide—his body filling the empty space in his bed, in which I had curled and wept quietly in the knowledge that he meant everything to me and that life was worth nothing if he were not a part of it—he had words for me.

“If that ever happens again you have to finish it.”

I pretended not to know what he meant.

“I want you to finish me with a pillow,” he said.

“I’m no killer.”

“Promise me.”

“If I was going to kill anyone, the last place I’d start is with you.”

“I’m not fucking around, Holmes.”

“It can’t be tonight. I’m getting my nails done,” I said.

I wasn’t trying to make light of his pain. It’s just that it all hurt too much to talk about.

He became deadly serious—looked at me with those I-could-shank-you-where-you-stand eyes, and spoke these words in a low tone: “Eh, so don’t forget, Holmes—you owe me.”

“It’ll take time to stash enough dope to try again. In the meantime, you’re here with me. You’re O.K.”

Calculating a fatal dose was a Ph.D.-level skill, considering Chino had been a junkie for most of his fifty years behind bars. It had taken weeks (try taking away a portion of a junkie’s daily habit and see how far you get) the first time around.

I told him to hang on; new discoveries in medical science were happening every day. I told him to trust me, that he’d get his compassionate release, and soon he’d have all the pussy he could ever want. He smiled then, as if everyone he’d ever loved was in the same room, happy to see him, and for a moment I felt relief.

That morning I got him out of bed and helped him take a piss, and then I sat him down on his bunk to brush his teeth and shave him. I put on his pants and socks and shoes. I combed his hair and we waited for the cell door to open.

A hundred inmates stepped out onto the tier from their cells at once—faster, younger guys, half of them rapping, all hormones and macho bullshit on this range we used to rule. They streamed around us to the cellblock grill gate, gangbangers, punk kids, wearing their pants around their asses or hanging round their knees. We worked our way to the cafeteria but we moved slowly—like a steamroller this mass of men—swept into it, the screws hurrying us along, as if we were twenty-five-year-olds.

A guard yelled, “Tuck it in.”

“What? What?” I asked.

“Tuck it in.”

I’d forgotten my glasses in my cell and couldn’t read his lips.

“Tuck in his shirt, now.” He knocked Chino’s cane out from under him. “Are you deaf? Tuck in his shirt.”

Breakfast. Lunch. Count time coming and going. Coming and going again.

Before I came to prison I worked in a warehouse for an asshole. Financial trouble and personal woes weren’t the half of it. Suicidal at 2 A.m., I was sitting in a bar and drinking and sharing such things with the only people one can share such things with—strangers—and because the desperate will grasp at anything to keep themselves from falling, the next day I found myself at the airport with eight hundred grams of heroin strapped to my body. I got fifty years and a transfer to this prison, housing seven thousand men. There is nowhere to lie down without touching despair.

I’m not trying to say I’m a victim—there’s another one of those terms, like “cycles of abuse” or “anger management” from a psychologist’s vocabulary list—it’s just that everyone has a story that starts, “Let me tell you about the time . . .” Who hasn’t been fucked around? Who hasn’t dreamed of revenge? Who doesn’t wish they grew up happy?

Back when I was a kid, my dad and uncle used to get deep into their cups. My uncle would push his way in through my bedroom door. Every time the door would squeak open, I knew what was going to happen, starting with my uncle calling me sicko and ending with me embarrassed, cleaning myself. When Uncle Gode left, he was always laughing.

Chino got his walker and, having regained some small amount of mobility, rallied.

But the independence gave him the means to start entering other cells by accident, thinking they belonged to him. He would get himself into trouble because of little gestures like staring, when he didn’t even remember who he’d been looking at. One day, when the screws weren’t around, he took a shit-kicking in the commissary because he’d lost control of his bowels and everyone was mad at him for stinking it up.

It was getting harder and harder to convince myself that what was right for me was also right for Chino, and the old cons had started talking.

In Chino’s healthier days he would have said, “You fucker,” in that way of his: chin up, looking at me for making him suffer, for making him, as I’d always done, bear the weight for the two of us. Chino, who’d always been the one to carry the conversation, the fight—you name it. Anyhow, the old cons felt so terrible about what had happened, they took up a collection. By the end of the afternoon, we had more than enough heroin to kill Chino.

So then I told the guard that Chino wanted to die, that four lousy ibuprofens weren’t enough, that he no longer even remembered why he was in prison, that I’d found him crying with a shoe in his hand, that he couldn’t remember the rules and was getting shit-kicked for it by guys who had no respect, who weren’t good cons, and how I needed to protect him because guards like him weren’t always around, and how I fetched his commissary, and cleaned the cell, and helped him with physical therapy, bathed him, diapered him, gave him a clean shave.

The guard told me I was helping him just by being there, and then he said he’d leave it alone. He said if I did it, killed Chino, no harm would come, no consequences.

“We’re not all dicks, man. I get it.”

“But I don’t want to kill him. I want him to get treatment. I want him to get pain meds. I want him to get compassionate release.”

“You do you, man,” he said. “I’ve heard you. You tried. You made your point.”

That night was the first night I’d had to diaper him before bed. The overhead light threw shadows into the valleys of Chino’s blanket, and I listened to his raspy breathing, envisioning the grim reaper above him, ready to snatch what little life remained, unable to do a goddamn thing about it.

I woke full of guilt for allowing Chino to suffer—and all to satisfy my own sadistic need to keep him around. I thought about going back to sleep and pretending my bed was any bed, that I was anywhere, and imagined how it would feel to let go and fall from this life. I dreamed about breaking out with Chino so he could die a man, a free man, because a man can’t be a man if he isn’t free.

Chino woke up at 3 A.m. Saving for the fatal dose had put his body through hell.

“I can’t sleep, I’m in so much pain.”

Chino was screaming. The tier, yelling, “Shut him the fuck up.”

“Shh, shh, shh,” I whispered, stroking Chino’s hair. “You’re O.K.”

His eyes were afraid.

“Holmes, I don’t want to die in jail. I can’t die in here,” he said.

“I’ll get the guard.”

“I don’t want to be transferred to the infirmary.”

I tore out my hair listening to the screaming. I felt like a man standing on a land mine, only temporarily alive. All I had to do was put the pillow over Chino’s face, hold it there. In a fit of strong emotion, like what the chaplain talked about, I found his heroin. He stopped screaming when I touched his arm.

“Is it time to go now?” I asked.

The entire range was yelling at me: “Shut him the fuck up.” Every one of them at some point, had been innocent. Like a baby, I held him in my arms, the rig ready.

He couldn’t struggle. I gave him the heroin I’d been holding for him—gave him an overdose, all of it—and laid him down when he became limp. Chino drifted off but he was still in pain, because when he woke briefly, he was moaning.

He was breathing in a rough-edged way.

“Finish me with a pillow. That’s what you got to watch for.”

I’m not a killer, but maybe there is something worse than being a killer. Maybe the worst thing you can do when someone is howling in pain is not be a killer. It occurred to me then, I could follow him where he was going. How do you remain a good friend when what your friend needs and what you need are opposites? Chino wanted to leave this earth. I needed him to stay.

In the beginning, I didn’t think I could do life, but Chino turned me around.

He taught me life was my only possession, and so to respect life. He taught me how to survive one day at a time, and said it was important to die a better person than I was before I came to prison. But I failed him. I snapped. I killed. You wanted to know what makes a killer. Well, I’m sure my next cellmate will be a gangbanger, and if I get sick I don’t see him backpacking me to the showers. He’ll cut my throat with a shiv and drag my body to the showers for a screw to find me, and no one will see a thing. When you can’t take care of yourself, you’re a victim. And inside, there are only predators and victims. And since Chino always kept me alive, I don’t know what will happen next.