It was early August and Qaqqasiq had spent most of the summer playing by herself. Boredom had driven her to this moment with some of her schoolmates. She had seen the other kids taking turns racing bikes up and down the dirt road in front of her house, and worked up the courage to join them. They sniggered and whispered among themselves as she slinked over.

“Can I bike too?”

“You can race with us if you do something first,” one boy said.

She looked at the ragged blue and yellow bike with envy. It was in rough shape and covered in dust, but it sure beat no bike at all. She had been adopted by her aunt and uncle who already had four children of their own and little money for bicycles.

“What do you want me to do?” she asked with resolution in her voice.

“Huck this rock at that window.”

The boy pointed at a nearby house. They all knew the old man who lived in that house. He was Qaqqasiq the angakkuq, the only practising shaman in Iqaluit; little Qaqqasiq knew this because her aunt had complained about him many times. Her family were devout Anglicans and her aunt had feared him as a child, after the local priest warned that he was a “conjurer of evil spirits.”

She’d overheard her aunt complaining to her grandmother about him one day after church. “It’s 1983 for crying out loud! Inuit don’t use magic anymore.”

Qaqqasiq hesitated, but thought about spending another day playing in the dirt by herself and picked up the large stone. The others jeered behind her as she took a running start and launched the fist-sized rock through the dark window of the old shack. The pane was thin and made a low, hollow sound as it broke. The rock had made a large hole just before the rest of the glass fell like icicles out of the grey wooden frame. Qaqqasiq immediately felt a surge of guilt as she realized all the windows on this side of the house had suffered the same fate. She turned to see the others racing away on their bikes and yelled out for them to wait for her. When she heard the creaking of the door she ran up the road until she couldn’t see the old man’s house anymore.

She knew he had heard her and, being her neighbour, he was sure to recognize her voice. She moped around the playground, worrying about what Qaqqasiq would tell her aunt and uncle, and finally dragged her feet home several hours later when she got tired and hungry. To her great surprise, nobody was angry with her, or even noticed that she had come in for dinner. For the next few days she anxiously waited for a knock at the door that never came, and soon she felt comfortable enough to leave the loud and stuffy house to play out in the sun—alone as usual.

It was a warm, bright day and Qaqqasiq, hearing the crunching of tires on gravel, shut her eyes and turned away to avoid getting a face full of the dust that was about to erupt in the wake of a 1975 Chevy pickup. When she opened her eyes again she saw trouble—her hulking cousin Miali was approaching with some friends. She braced herself for whatever was coming next. No matter what it was, she wasn’t going to like it.

“Eli, you wanted to throw rocks at a dog? Look there’s one!”

Miali pointed at Qaqqasiq, sneering at her as she picked up a stone. Her friends followed suit. Eli chuckled and so did most of the others, but Miali held up her hand and they fell silent. She looked angrily at Qaqqasiq’s shirt, a brand new baseball tee with red sleeves and culture club printed across the front. Qaqqasiq’s aunt had ordered it for Miali from the Sears catalog but it didn’t fit.

“Take off my shirt, dog!”

“It’s not yours. You’re too fat! mialikallak!”

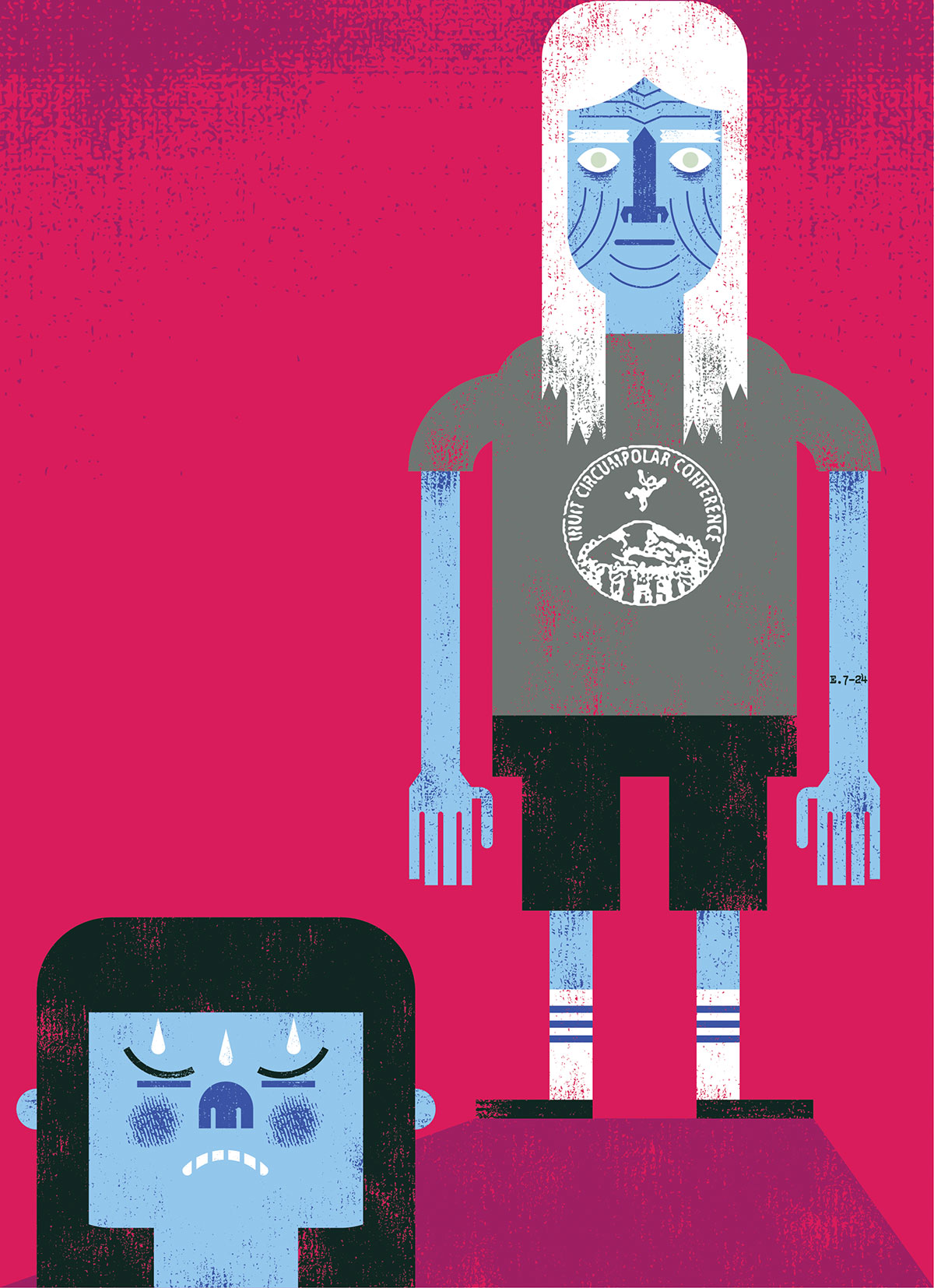

It was the simplest kind of insult—adding “fat” as a suffix to her name. It was also the wrong thing to say, but Qaqqasiq knew she was going to get beaten anyway. She might as well humiliate Miali while she could. As she held her breath in anticipation of the stoning she was about to endure, a shadow enveloped her. The others, with masks of horror on their faces, dropped their rocks, twisted back toward the road, and ran away yelling incomprehensibly. Qaqqasiq turned slowly, sensing her saviour was possibly even more frightening than her attackers. Towering over her was an ancient man with wild, white eyebrows that looked long enough to poke out his own eyes. If she had not been paralyzed with fear, she might have even wondered if that was how he had gone blind. He had milky white eyes that matched his coarse, long hair, and severe lines in his face that gave him a look of perpetual anger—it was easy to see why he was so frightening to impressionable young souls.

“Atikuluuk—my namesake, come in for tea,” he commanded, and little Qaqqasiq followed him inside without a word.

She stood close to the door of his plywood porch trembling, until he waved his hand for her to sit down.

“How did it feel to break an old blind man’s window?”

Little Qaqqasiq was confused by his tone. He sounded more curious than anything.

“Bad.”

“Why did you do it?”

“So the other kids would play with me. They said I had to break your window to race bikes with them. I’m sorry.”

She had her head down and was mumbling into her lap.

“You should always keep your head up when you speak. Only shame bends us down. When people tell you what to do or how to act, think of how it felt to break my window. Think of holding your head up and telling others about what you have done, and maybe you will make better choices in the future.”

He stood and walked to the kitchen, where there was tea already boiling on the stove. She relaxed a tiny bit when he put the chipped white tin cup in front of her and she smelled the orange pekoe—it reminded her of camping on the land with her grandmother.

“I was friends with your grandfather. He was like my brother. Did you know that he asked your mother to name you after me before he died? They were going to name you Iola, after him, but he wanted you to be strong—he wanted you to have the power.”

She remained silent, sipping her tea, unsure how to respond. They sat quietly for several long minutes, drinking.

“Sometimes I talk to you in my dreams,” she said finally.

“Yes. I have been visiting you recently. Do you have any questions for me?”

She looked at his worn face and imagined how long it had taken the wind to blow his skin into the cracked and drooping landscape that stared at her now. He wore an inuit circumpolar conference jam! 1983 T-shirt and she noticed a small tattoo on his left forearm. It read “E.7-24” in slightly blurry sailor-blue ink.

“What’s that on your arm?”

The old man laughed, and rubbed his tattoo automatically.

“Don’t you know about E-numbers? Too young, I guess. I tattooed mine on so I would never fail to remember how the qallunaat treated us. People like to forget. But angakkuit never forget. You’ll see.”

Little Qaqqasiq, whose fear of the old man had dissipated by now, was leaning close, eager to hear all of the forbidden things Qaqqasiq the angakkuq had to say. Other adults had never been so frank with her before, and she wasn’t sure how long this might last. As she leaned in, she noticed the old man’s eyes change. They looked as if they could see again. His face, too, looked younger somehow. He began to speak.

“I am from Kimmirut originally, like your grandfather. That’s where we first met the qallunaat. They had medicine, food, and bibles for us. It was 1941. I remember I was about your age, maybe ten or eleven when they started with the E-numbers. The government wanted to count us. Back then we were born and given only one name, but it was too confusing for them. They had tried fingerprinting everyone, but the priest said we should not be treated like criminals. Ha! Instead, they treated us like dogs. We got our Eskimo number when the R.C.M.P. officer pointed at us and wrote our name down next to the number. Then they gave us leather tags with our number stamped on it, with a hole at the top so we could wear them around our necks.”

He sighed deeply and seemed to return to the present. Qaqqasiq was shocked by this information and they sat quietly for a moment as she soaked it all in. The elder Qaqqasiq turned his head slightly toward the little girl and she saw a different face now. The madness she had imagined so many times while listening to stories about the angakkuq’s “black magic” was not present in this face. There were hard lines and ferocity, but she also was surprised to see kindness hidden behind his untamed hair.

“Why is everyone so scared of you? Do you do bad magic?”

“No. People are scared of me because I am different. I never stopped practising my angakkuq traditions, and people don’t like that. I didn’t follow them into Jisusi’s house to pray, so they convinced themselves I was a devil. There are bad angakkuit, but I don’t do that kind of magic. Mainly healing, and we Inuit need healing more than ever. Most of us just don’t know it.”

Old Qaqqasiq stood and took away their tin mugs. While he rinsed the cups, little Qaqqasiq decided to speak.

“They treat me bad. Can you teach me how to fix that?”

“Who does?”

“Everyone mostly.”

“That is because you have power and they know it. Inside themselves they know it. Come back tomorrow. I’m tired now. You are my namesake, and I will teach you how to survive.”

She stood up, full of a kind of excitement she had never felt before. Her fingers were tingling and she walked out of the old shack with purpose.