I’m in love with you and the dog is licking herself.

That’s my life.

We lay on the bed, our smell rising up in the steam heat of this dismal apartment, our ugly skin the best part of our lives together: your arm under my head, and my ugly face turned into the small perfect heartbeat that taps out of your sunken chest. Our naked legs tangle together in a spidery imitation of hair and skin. Our fluids dry all sweet and sour, yours in mine and mine on yours. And I love you. I love you from the only beautiful part of me, the part that neither of us can see.

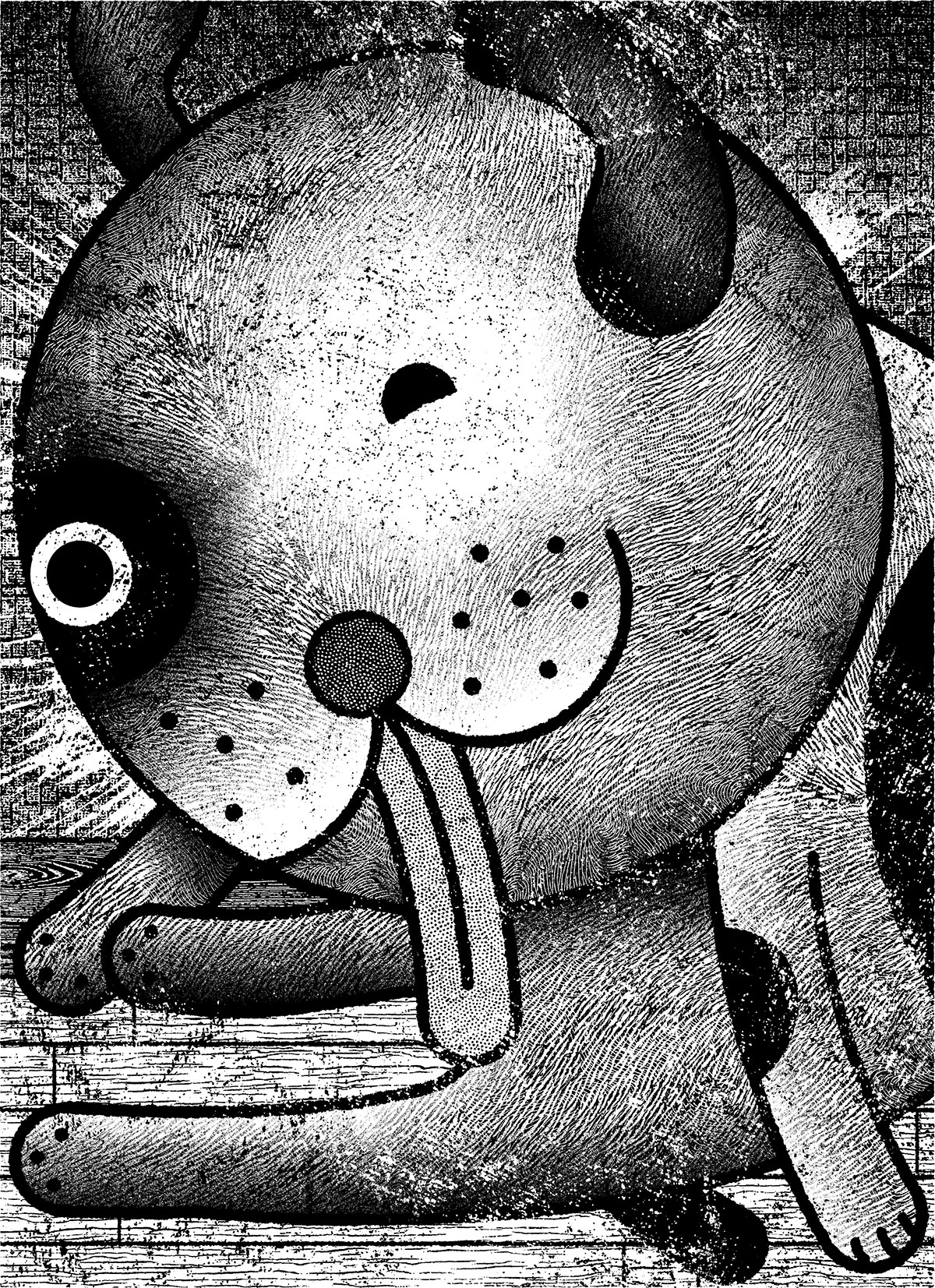

On the floor next to the bed, the dog has stopped scratching, stopped shaking the room with the thwack of her leg and the jangle of tags. Instead, she’s started licking the place between her legs. Making the room sound like rain. And it’s gross, like us, this inappropriate lapping.

“O.K., get off,” you say, squirming out from underneath me. Rolling up off the mattress, your body falls around you again, like a bird spreading its wings. Your ass is like a sponge that has sopped up something heavy. A sprinkle of acne scars your shoulders. These are the leftovers of adolescence as we pull up into our thirties. You drift away from me.

You walk out of the room slowly, and in the light of the bathroom doorway, you push your hair out of your eyes. In silhouette, you could be graceful, if I didn’t know you the way that I do. If I didn’t know.

I put my hand between my legs and feel the place where we meet. It’s sticky.

In the other room, the pipes whistle. You run the water, and as you wait for it to warm—though I can’t see you—I know you are standing over the toilet, pissing.

It’s terrible really, to live this way. The first time I saw you, I fell in love with you. I knew at that exact moment that—for better or worse—we would be together forever. Until that day I had never seen anyone uglier than me. Or at least, no one who hadn’t been deformed by some birth defect or accident. No one who had been marred by a simple meeting of bad genetics coming to the forefront without any nameable disability. Do you know what it means to feel that way? You do, I know you do, but it still makes me self-consciously sick inside. My whole life, the only time I felt good about myself was when I saw someone less fortunate than I was.

I tried to be good. I was good. But then it would creep up, every once in a while, when I was lucky, when I was unlucky. It would be there, like the boy at the back of the bus who wore puppy dog sweaters when we were in the eighth grade, their blotchy blue yarn snouts and banana-shaped ears stitched onto the pockets.

He was my salvation. Him, and the rare—the few—others like him. He tried to speak to me, to make friends, but I never let him. We were alike, but not. After all, he wasn’t really ugly, just faultlessly stupid. After a while, our silence became special. It stretched from front to back, over the seats, an invisible cloud of love and hate. I could feel him staring at the back of my head. The wind blew my hair all around, making a wild nest that I tried and tried to keep down. Sometimes I would gaze up into the large rectangle of the driver’s rear-view. I would catch him staring; he was too dim to realize I could see him in the reflection. His mouth was slack, his eyes sad. I did love him. I did, in a way. I imagined that he drank milk at night, that his mother still brought it to him in bed and kissed him, that he dreamt Disney characters would come and help him capture all of the smart, beautiful, normal kids and send them away. That one day he and I would meet on the Island of Misfit Toys. But we shared only that—silence and a few angry glances—a secret attraction and aversion I controlled cruelly. Ignoring him was worse than anything the other kids could do to him.

Thankfully, by the time I met you, I was old enough to know better. Old enough to have developed self-interest, a strange, disjointed, macabre fascination with myself. Not narcissism—they say that that word is always misused—but you know what I mean. I’m sure you know the word for it, even though I don’t.

No, by then, ugliness had become a kind of light to me. I had grown used to it, had even learned to look for it.

In my last year of high school, I developed an enormous crush on the fat girl who brought her father as her date to the prom. She was stronger than I was. She had a satin fuchsia dress. She at least had someone to dance with. She didn’t care what they thought. I had only the girl with the harelip who got straight As and talked to me about mathematics, as if that could be considered conversation. We huddled together, daring one another to down the spiked punch, poking one another in the ribs, saying no when one of the hockey guys ambled over and asked her—then me—to dance. We were wise and gutless. It was only a joke. And on the way home, we vomited up peach schnapps behind the Mac’s convenience and confessed we each wished we’d said yes, even if we knew he would go back to his friends, the big man collecting bet money. To feel for just three minutes his taut body holding us tentatively, above our heads his bright skin, his velvet cheeks, his valentine lips, his eyes like plums. Why do I still remember?

The girl in the fuchsia dress became a journalist. The harelip girl became a professor of mathematics. The boy with the liquid eyes knocked up his girlfriend and then left her. He became manager at a McDonald’s. He stopped playing hockey, balded early, got fat. Scenarios like this helped me to survive. Kept me from locking myself in the bathroom, holding my father’s razor like a crucifix.

When I was still an adolescent, they told me they could fix my face. Part of it, anyway. One night, after my parents had gone to sleep, I got up and, in the orange glow of the night light, I stood staring into the mirror—for over an hour. Looking in turn at the different features of my face. My eyes. My nose. My jaw. My mouth. Coming back to my eyes again.

I said to myself, “This is my face.” To change any one part of it would change the entire thing.

“This is my face,” I said.

I met you in a crowded room, everyone talking, someone passing around a sweet-burning paper cone full of pot. People were dancing in the foot or two of space between the living room and kitchen of this little apartment. And then there was you, sitting in the corner, every gesture you made slow and deliberate, and everyone in the room (who wasn’t dancing or stoned) looking at you, gathered around you, gradually moving chairs closer to you or sitting down on the patch of worn carpet in front of you, all of them looking and listening.

You struck me as a circus performer. You were fat-thin, your hair long-short, the fingers that held your cigarette swollen like those of a midget (though I know that’s not what they like to be called). You gestured with this lit thing, gracefully, turning your head, your large round eyes, your mouth pulling open, pulling open, pulling open before the words would come out. You weren’t handicapped. You weren’t retarded. You weren’t even ugly. You were beautiful, the only one there who wasn’t uniform. They all wore jeans and brown loafers and iron-flat buttoned shirts. You wore an oversized T-shirt and jogging pants and a pair of old runners. I couldn’t take my eyes off you. And when I got closer, I could see why they all stared too. The things that fell from your mouth were unbelievable. My walking trivia box. My living history boy. My gorgeous genius.

I broke into a sweat. I knew you could never love me. Right then, just like that, my mind was made up. I would love you for all I was worth, if only you would look at me, just look at me.

When we made love the first time, it was as if we were kids in a playroom, trying not to get caught shoving plastic toys down our shorts. Your cock was like a small mouse inside me. Furry and brown, ready to leave its leg behind in its rush to get away. We made love again and again until we got better at it. Until we were like two adults in a hotel room instead. We made love until we were dirty and gasping. We were ugly, we were the ugly people, and we had no right to this. We did it again, just to be sure. Just to show them. The non-existent them we felt were more real than ourselves.

Months and months of this.

And then, one day, me pissing and moaning about the assholes at work, an asshole on the bus, an asshole on the radio saying some asshole thing, people moving around not wanting to sit next to me, some kid looking at me like I was more disgusting than a turd on a stick. Over an afternoon table, this conversation drifted above a plate of nachos, some nondescript band on the jukebox, and you said, “One day you’ll look back, and think these were the best times of your life.”

“I hope I would never think that these are the best times of my life.”

“Yes, you will,” you said. “You think you’re ugly now? You’re only going to get uglier.”

“Well, thanks,” I said. I couldn’t believe you could be so cruel. “Thanks a fucking lot.”

You leaned back, all confidence, the smell from your armpits hitting me gently as you stuck your palms behind your head. That tangy one-time aphrodisiac, now greasy and gross as congealed cheese.

“The same goes for me,” you said. “For everyone. You should see things as they are. It’s never been as bad as you think.”

And then you launched into some example, or string of examples. You were a double-major in history and religion. In spite of being an atheist. You have an example for everything.

But I wasn’t listening. I began thinking about the differences between men and women—and how I would only grow older and uglier, but you would grow wiser—and how an unattractive man is never as undesirable as an unattractive woman, particularly if he is intelligent or distinguished in some way—and how when we do go out you are the one that people want to make conversation with—and how I will sit to the side exchanging the most menial pleasantries—how people have always clustered around you, in spite of your looks—how you are the kind of person people wait to speak to—and I am the kind they walk away from. Sometimes mid-sentence.

A giant fear began to rumble through my stomach. I knew you would leave me, knew it as certainly as I had known six years before that we would always be together. You would grow successful—you were already—and there would be women—and there would be flirtations—and they would be beautiful—and they would be open to you for the first time—and then I would not be interesting. I would just be ugly. Uglier, even.

Were you with me because you loved me? Or because at the time I was all you could have? Did you keep me because you wanted me? Or because you just didn’t have the heart to get rid of me?

That night, for the first time since I was a teenager, I locked myself in the bathroom to cry. You tried to come in, but I’d locked the door. The knob turned and stuck.

“Are you O.K., babe? ” you called through the door, easy-like, the way you are.

“Go away,” I said, sniffing back mucous. “I’m taking a shit.”

“But you’re taking so long…? ”

“Must have been something I ate,” I lied. The only truth in it was that my guts felt like a needle had been put through them repeatedly, sewing them into a fist.

“The dog’s desperate to go out,” you said.

“Then you take her.”

At a certain point, hate goes past hate and, if not back to love again, then at least to liking. Truly attractive people had become that to me long ago. After I met you, their beauty stopped bothering me.

Until I met Norman.

It was the same as when I met you, only worse. I was completely repulsed. The idea that I would want to lay a body like mine next to a body like his sent me into cold sweats in my seat. He was flawless and beautiful, but only on one side.

He worked two cubicles over. I was grateful for the fuzzy grey half-walls between us. It meant I didn’t have to look at him. His head was shocking, its short bright hair like an ad for a shampoo commercial. He had the body of a greyhound. His shoulders were fists and his waist was abominably narrow. When he turned sideways, he was all muscle and rib cage. I had never seen anyone so conventionally perfect. But when he turned to the other side, his skin pulled away in white ridges, and he was half-skeleton, the long scars running in vertical wrinkles across his gorgeous face. His pocked neck. His twisted shoulder flesh. His hard, hollow skin. He’d been burned.

I had never been attracted to anyone like him, had never seen the circumstances of our lives being as hard as those of our birthrights. How golden his life must have been, and then to have it all yanked away, scalding…How far down his body did those bone-like scars go? Did they diverge across his chest? Or stretch all the way over his hip bones? I wanted to feel him tear at my skin, feel his anger at the injustice, feel it manifest in the blunt, mesmerizing beat of lust.

I kept an inventory of his habits. He was polite—and frugal with himself and with others—and he was a drink-box bachelor, his lunches nothing but gym towels he hung to dry on the hook inside his cubicle—and he kept a bottle of salve inside his desk drawer—and it smelled like pine needles and eucalyptus—and, to make matters worse, a good thick novel he replaced every week with another—and he was a two-finger typist, though almost as fast as a professional—and the keys clicked underneath the clean crescent moons of his impeccable nails—and when he walked by, he moved like a cat—and he always smirked instead of fully smiling as though he was thinking something dirty—and the skin on his burned side was the colour one imagines an angel’s wing would be—and around him I felt myself lift, my breasts become little pieces of lace, stitched on.

At night, you moved over me like a ghost, and I no longer felt you or smelled you. Afterward, I would walk the dog.

Out in the snow, she padded in circles, sniffing, pushing her nose down into the ground, long strings of saliva collecting ice.

“Why can’t I have this? ” I asked. I whispered it out loud into the cold empty night. “This,” meaning Norman, meaning something beautiful, or half-beautiful. “Just once,” I thought, “why not me? ”

The dog squatted and did her business.

When I came back in, you were uglier than ever.

I locked myself in the bathroom. I shaved my legs. I took a loofah and did my feet. I pulled hairs from my nipples with tweezers. You knew me. You knew I was ugly and you had stopped seeing my ugliness. To Norman, everything would be obvious. The hairs would jut from my body like curls of copper wire. My feet would be rough as concrete. My thighs would be soft and wrinkled as a lizard’s underbelly.

Norman liked me. No one had ever liked me before. You had loved me, but I doubted now that you had ever liked me.

“You’re very interesting,” he said, letting the emphasis fall on the first part of the word. Norman said I was clever. Norman said I was hilarious. Norman said I was sweet. He did not say any of the things that other people had said. He did not say, “Do you ever think of getting your teeth straightened? ” or “Have you tried contact lenses? ”

We went for coffee after work. It became a regular thing. We stayed out very late and never talked about work. He told me about his apartment (above a convenience store), his previous girlfriends (one shallow, another fickle), other places he had lived (the West), the places he had travelled (the East), and what he most desired (to accurately document the time we were living in). I desperately wanted to ask him how it had happened, how he had been burned, but I knew everyone else must have asked him that. For Norman it must have been the equivalent of, “Have you ever tried to do something else with your hair? ”

He smiled his half-smile. He smirked, and smirked, and smirked some more. His mouth was like a faint red comma pencilled on a piece of paper. It was obvious what he was thinking. We were going to have an affair. We were going to have a wonderful, awful affair. I glanced in the mirror across from our booth and I saw a man and a woman. In the dim lighting of the diner, I could not see our faults, only our profiles. “That is what she looks like,” I thought to myself, “the woman who has an affair.”

In the shadows of the parking garage, Norman’s car smelled like leather and oil. I thought of you, just once, as I was getting in. Then Norman’s bad side was to me, and he leaned in and kissed me on the mouth. His tongue was softer than the rest of him, and that made me nervous. I pulled to the side and wound up laying my lips against his scars before I realized it. He put his hands up my shirt without asking, and then, before I realized it, he had slid them down into my lap. He moved with the fast confidence of a beautiful man, even as my mouth was pressed against his ugly part.

Up close he didn’t look ugly or beautiful. He just looked like a stranger.

“I can’t,” I said, “I can’t.” I pushed him away from me.

He smelled all wrong. Like mint leaves and pine incense.

“What do you mean? ” he said, and when I started to cry, he slapped the dash hard, and not with the flat part of his hand. He got out of the car and made some adjustments to his clothes. When he got back in, he revved the engine and drove too fast.

I stared into the side-view mirror all the way home. I could see part of my face in it—my mouth—my ugly mouth and the black side of this stranger’s car.

Even ugly people could be assholes.

When I entered the apartment I could tell something had happened. Things had been thrown here and there, newspapers and a couple of cardboard boxes. Your old pair of shoes tripped me in the doorway of the bedroom. A blanket hung over the arm of the chair. A strange stale smell lingered in the air.

Everything was much too still.

Panic threw a punch at my head and I gripped the door frame. Then I realized what exactly was so wrong: you were gone, but so was the dog.

At the emergency vet clinic, you slumped among a long row of plastic chairs. Above you, a television strapped to the wall played a late-night infomercial. As I came through the doors, I watched your face hanging there, blotchy, a clown’s face, your expression fixed, permanent. You stood up but didn’t move, and for the first time, I think, I really knew you needed me as much as I did you. I forgot what I had done an hour before and I grabbed hold of you.

“Is she all right? ” I asked. I could feel fear on your skin like an extra layer. You gripped my back with your hands, your fingers spread.

On the phone message at home, you had explained the oceans of puke, and how she had crawled half under our bed—you thought—to die. The vet didn’t know what was wrong with her.

A wave of your perspiration hit my face as you pulled me into your shoulder. “I’m sorry,” I said, even though she was my dog, technically. Even though I had been the one crying all the way over in the taxi. Even though I was the more wretched of the two of us and didn’t deserve to be anywhere—even here—with you. Your body felt bumpy and right, warm and accepting through your old grey sweatshirt.

“I love you,” I said. It was all I could think of to say.

They let me go into the back to see her. The room where they had her was about the size of a bathroom, bare except for this animal tethered to an I.V.

She sprawled on her side in the middle of the floor, and didn’t move when I came in. I could tell by the smell that she had let her glands go earlier. The bitter stink still streaked the air. Her back end was dirty—dirty smeared clean—as though she might have defecated on herself at some point and some intern had made a half-hearted attempt to wipe her up. I said her name, but she still didn’t move. She found me with her eyes, but showed no sign of caring. Her eyes had turned yellow with jaundice. Her dark pupils floated in two small pools of pus in her long face. I had never seen anything so pathetic. She was feeble, pitiful, and sad.

I fell to my knees and put my hands in her fur, stroking the top of her head and behind her ears. “Please don’t die,” I whispered. “Please stay with me. Please. Stay.”

Behind me, I could hear you trying not to cry.

“I love you, pretty puppy,” I whispered. “My beautiful doggy girl.” I put my lips to the crest of her crusted nose and kissed her.