Hal Niedzviecki is obsessed with fame—not necessarily his own, but the type of fleeting fame that makes others thrust themselves into the spotlight. Talent doesn’t seem to matter, he observes; fame junkies just need their fifteen-minute fix, to feel the thrill of admiration, the sheer sense of being everywhere, the surety of “specialness.” In Niedzviecki’s perfect world, there would be less of this type of fame and, he says, almost wistfully, “more people doing cool stuff.”

Niedzviecki’s own experience in the spotlight has lasted much longer than fifteen minutes, long enough for him to do some “cool stuff” of his own. Since the late nineties, he has produced a short-story collection, three novels, an anthology, three books of analysis on the state of culture (both popular and alternative), a ghost-written biography, and a city-dweller’s almanac, not to mention countless newspaper and magazine articles. He has appeared frequently on radio and television, and along the way also managed to co-found Broken Pencil, a quarterly magazine dedicated to zines and D.I.Y. culture, and its corresponding annual zine fair, Canzine. In the process, Niedzviecki has become one of Canada’s most interesting—and bizarrely original—cultural commentators.

Niedzviecki’s non-fiction topics range from reinventing Judaism through pop culture to the dirge of “stupid” hipster books available near the cash register at stores like Urban Outfitters. In its crudest form, his fiction is made up of flashes of masturbation, pornography, cyborgs, shit, piss, and sex. It’s visceral, it’s emotive, and, in the words of the writer and editor Darren Wershler-Henry, with whom Niedzviecki co-wrote The Original Canadian City Dweller’s Almanac, it’s “some of the weirdest fiction that’s being produced in Canada today.”

Yet, past the surface, Niedzviecki’s stories can also be softly tragic and even tender. An early short story titled “Between Two Old Ladies” contains only the six words, “There is a sudden smell here.” His novel Lurvy is a blow-job–filled retelling of E. B. White’s Charlotte’s Web, from the perspective of the farmhand. And in the cyberthriller The Program, Danny, a boy who may have suffered sexual abuse at the hands of his uncle, grows up desperate to meld himself with his computer.

Despite some touches of sublime weirdness, Niedzviecki’s writing is, as Anne Collins, who edited and published two of his novels for Random House, says, “so serious it hurts.” That seriousness involves the balance in Niedzviecki’s fiction between his provocative brush strokes of society at its most animal—or most human—and a thoughtful critique of many of the most pressing issues in Canadian culture today. Unlike on TV or the Web, Niedzviecki’s layers can’t be coasted through. Reading his work requires thought, which isn’t always easy—explaining, perhaps, his modest but steady sales numbers.

“What is fiction supposed to do? ” asks Collins. “Is it just supposed to reassure us, comfort us, make us feel like we’ve gone to some other place for a week or two, or is it supposed to help us figure out what the hell we are and how we are mutating? ”

While some authors have little more to offer than the intellectual equivalent of a one-way ticket to Disneyland, and become famous doing it, Niedzviecki is engaged in the genuinely cool act of dissecting the world and trying to analyze the nearly seven billion people on it, including himself.

Growing up in Ottawa, Niedzviecki, like most teens, spent little time thinking about the future. By his own words, he was never “one of those kids who would go and write a novel at fourteen,” but he did read ferociously—a book a week, at least, during junior high.

Niedzviecki’s father, Sam, worked as a civil engineer for the Canadian government. In 1981, when Niedzviecki was eleven, Sam was sent to work on a project with the World Bank, in Washington, D.C. When he decided to make the move permanent, the family left their home in Ottawa, and Niedzviecki spent the remainder of his youth in the United States, attending Winston Churchill, a public high school in nearby Maryland’s well-to-do Montgomery County.

Churchill was the type of school Niedzviecki says encouraged “extra thinking.” It boasted a “fancy literary magazine”—Niedzviecki took the required English class to become a staff member—and a biweekly newspaper Niedzviecki also worked on. “I was like assistant, assistant arts editor,” he says. “Basically, all I did was sweep the floor.” Yet, despite his involvement in the student press, Niedzviecki still wasn’t producing much beyond his class assignments.

Writing, he says, somewhat elusively, is something he eventually “fell into.” It wasn’t until he moved back to Canada, to complete a bachelor of art in English literature and philosophy at the University of Toronto, that Niedzviecki attempted his first short stories—ones he says he remembers only vaguely. During the next four years, he developed a certain enchantment with words—and an inkling of their power.

In the essay “Darker Country,” published in the 2007 anthology Generation What?: Dispatches from the Quarter-Life Crisis, Niedzviecki reflects on time he spent on a study exchange in Scotland: “My classes ground me, give me something to do. More than that: they suggest a truth….The words read out loud by the professor fill me with an inescapable longing, a need that cannot be satisfied. Words create places, and places create words. Perhaps I can find words, create a place.”

Despite eventually earning a master of fine arts in creative writing from Bard College, in New York state, Niedz-viecki never dreamed he would be able to make a living as a writer. His choices, he felt, were to become a full-time journalist—a career that held no appeal for him—or bust. He settled on the life plan of taking low-stress jobs that wouldn’t exhaust his “mental energies”; for Niedzviecki, this included employment as an usher, security guard, delivery boy, data co-ordinator, and publishing intern. These jobs enabled him to work in his off hours on projects that held his interest.

One such project ended up being a magazine called Broken Pencil. Like so many great ideas, Broken Pencil began over a glass—or two, or three—of beer. Late one night in 1995, at the now defunct Beverley Tavern, on Queen Street West, Niedzviecki got on to the topic of starting a literary review with his friend Hilary Clark, who was then tending bar, and would later go on to become the first managing editor of a resurrected Coach House Books. Their original idea of reviewing independent journals and literary publications would eventually come to focus on zines and D.I.Y. zine culture, similar to the format of the U.S. magazine Factsheet 5.

The modern zine had come out of the nineteen-seventies punk movement, and by the following decade was entrenched in the independent scene—photocopied, stapled, personal forms of expression. By the nineties, the zine movement was at its peak, thanks in part to that decade’s supposedly lost, slacker generation—perfect timing for a project like Broken Pencil.

Figuring a budget of two thousand dollars would cover printing costs, Niedzviecki borrowed a portion of his share from his parents. “I told them I had to buy, like, a vacuum cleaner or something like that,” he says. Though the desktop publishing revolution was underway, technological—and, more to the point, financial—limitations still meant pasting up hard-copy pages to send to press, which was done using facilities at the Varsity, the University of Toronto’s student paper, where Niedzviecki had worked as the arts editor and for which he still wrote on a regular basis. Completed mostly during the paper’s late-night/early-morning off hours, putting Broken Pencil together was extremely labour intensive. But, by the fall of 1995, when the first issue was launched, Niedzviecki had followed through with a project that most leave at its pipe-dream stage. “That’s just the way I am,” he says. “I get something in my mind that I want to do, and I’ll do it.”

After the first issue of Broken Pencil was published, Niedzviecki was offered his first professional writing assignment. David Dauphinee, an editor at the London Free Press, had seen the magazine and was intrigued by the ideas it presented. He offered Niedz-viecki four hundred dollars to write a feature on zine culture. At that point, Niedzviecki’s day jobs consisted of working as a theatre usher and driving the Varsity’s delivery van—four hundred dollars was close to a week’s salary. The big payday and prominent placement in the paper’s Saturday edition got him thinking there was probably a better way to make money than hauling around bundles of newspapers. He wrote several more articles for the London Free Press and eventually began pitching assignments to other publications, including the Globe and Mail, the National Post, and This Magazine. Within five years, Niedz-viecki’s life plan had changed: he no longer needed to worry about exhausting his mental energies with menial day jobs; he was able to do what he wanted full time.

Before the decade was out, Hal Niedzviecki had become the It Boy for the independent community. What the London Free Press began—Niedz-viecki’s self-defined role as cultural commentator—practically every other news organization in Canada reinforced. He has, over the years, become the mandatory sound bite for anything the mainstream might consider weird or off-the-wall—though it’s not always a mantle he wears with comfort. Once, in a 2001 article for This, he described the guilt that came from a classroom speaking experience: “The hour went by slowly. After 50 minutes of fielding questions about how to write a novel, how to make a living as a fiction writer, how to self-publish, even I was sick of my own prevarications….I wanted to tell them, in my entire life I have never planned for anything to happen to me, nor do I have any good advice to impart.”

But that didn’t stop the media from calling. Over the next decade Niedz-viecki would be asked to comment on every aspect of independent culture, and was even approached to take the defence stand for John Robin Sharpe, a Vancouver man accused of disguising child pornography as literature. Niedz-viecki had become, despite his measured embarrassment, precisely what a 1998 Toronto Star profile dubbed him: the “guru of independent/alternative creative action.”

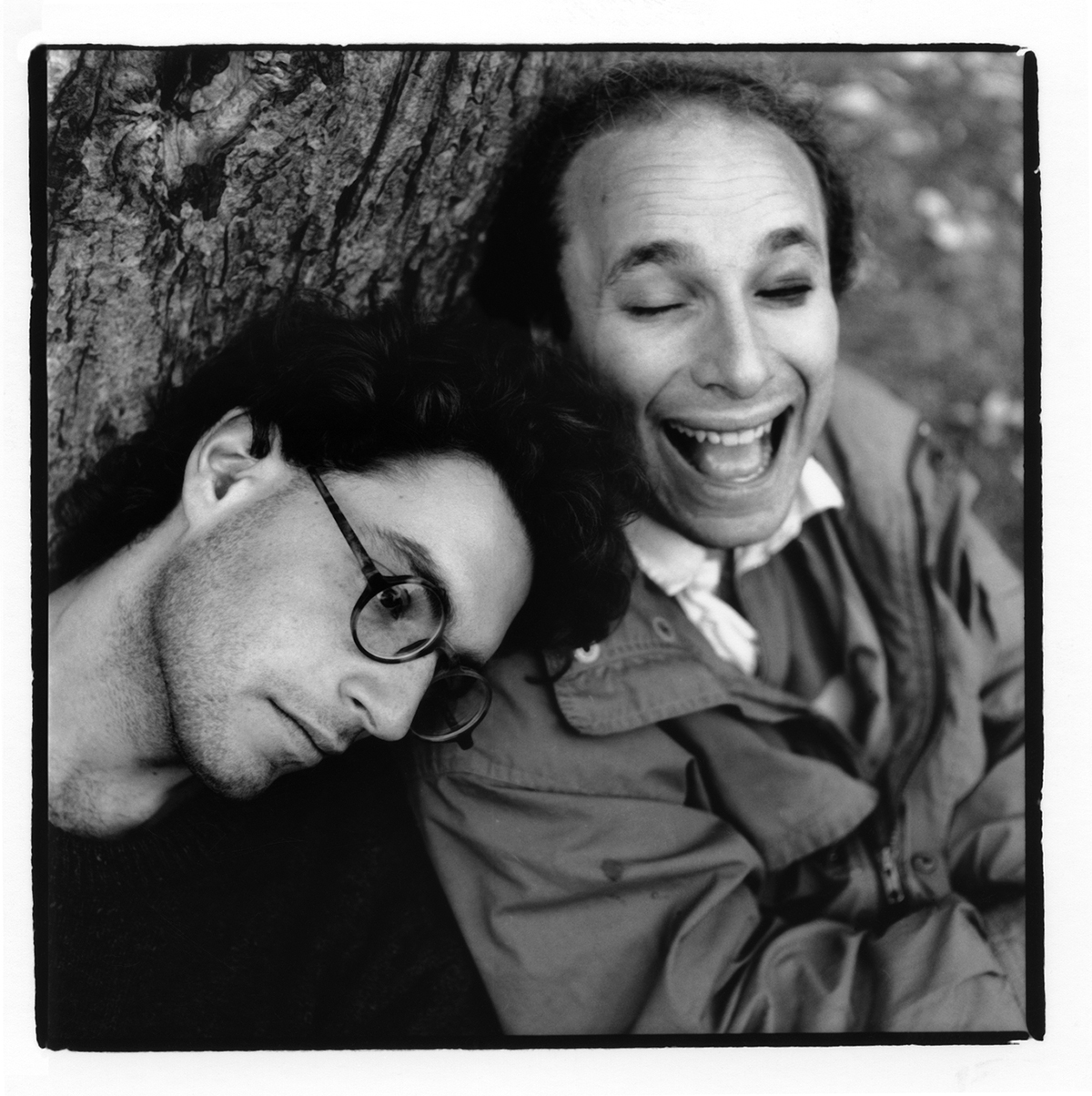

Niedzviecki and Ed Rubinstein, the mid-nineties musical duo Anger Only.

In recent years, Niedzviecki, now thirty-six and living in Toronto’s Little Portugal neighbourhood, has slowly taken a less active role at Broken Pencil. He gave up the editorship and day-to-day operations of the magazine in 2002, and now holds the titles of publisher and fiction editor. The duties of being editor-in-chief were like a “mountain” on him some days, he says. His current role allows him to spend much less time in the office, and more time on other projects. “Some days I think I love it, and I start thinking I’ll be publisher or fiction editor forever. And then some days I think I should get out of it altogether.”

Another recent event in Niedzviecki’s life that has caused him to slow down somewhat was the birth of his daughter, Elly, in 2005. Niedzviecki says he initially found it hard to settle into his new role as parent. “I wanted to keep doing what I’ve always been doing: late nights, drinking, lots of going out to things, experiencing the city and all it has to offer.” He has since altered his life accordingly, splitting child-care duties half the week with his wife of nine years, Rachel Greenbaum, a child psychologist, waking at five-thirty most mornings, and no longer writing articles that require an intensive nightlife.

However, Niedzviecki’s writing still doesn’t really reflect that he’s growing up. He’s yet to write a story about changing diapers, turning spoons of baby food into airplanes, or the general crises of a slightly balding father—which, with a full mop of hair, he is not.

Niedzviecki explains he’s developed a decade-long delay in his writing, taking the time to digest and find insights. Today, he’s still writing about twentysomethings; in ten years he’ll likely write about thirtysomethings starting families. (The change has already begun to creep in to some degree—in 2007 Niedzviecki published The Big Book of Pop Culture: A How-to Guide for Young Artists.) “It’s like you call a plumber,” he says, “and there’s the plumber, and he’s nineteen, and the plumber doesn’t have as much experience, and it may take him longer to figure out what to do. And now I’m the older plumber—I’ll come into your house and I’ll know what’s the problem with your pipes quicker.” Niedzviecki pauses. “I don’t know—that was the dumbest analogy ever.”

But a culture gap between Niedz-viecki and his intended audience may be beginning to show. In January, 2007, Niedzviecki wrote an article for the Globe and Mail on cruel bloggers. The article was written after a university student he had met and casually chatted with at a family gathering went home and described Niedzviecki on her blog as a “typical yuppy, cynical culture critic.”

“What kind of medium allows for such a casual invasion of privacy, for such offhand disparagement? ” Niedz-viecki shot back in the Globe. In other words, can’t bloggers think of their target’s feelings before they act?

Apparently not. The feedback on his article was quick and harsh. Bloggers with on-line handles like “Momo” and “SpecialK” posted comments that ran from mean (“You know how ‘miserable failure’ gives you George W. on Google? Is there a way to make ‘simpering pussy’ point to Hal Niedzviecki? ”) to cries of selling out (“He probably got paid to write that piece.”)

When asked if he’d seen any of the on-line comments on his piece, Niedz-viecki laughs. “I really did enjoy reading [them]. It was a lot of fun….I think in a lot of bloggers’ minds they’re against the Man. So if someone comes out in the Globe and Mail criticizing them, it’s the Man.”

Although comments posted by bloggers in the aftermath of his article were much more scathing than the blog that prompted them, Niedzviecki says the difference is that he knew what he was saying in the Globe would be entering the public sphere. “We’re sitting here, we’re doing an interview, so I know that everything I say is public,” he says. “If I met you in a bar talking about my erectile dysfunction problems, are you going to blog about that? I would think not….There’s a blurring of those lines.” Besides, he adds, the bloggers were really just proving his point by making the same quick judgments he so lamented in his article.

Even so, there’s more than one sad truth here. On one hand, Niedzviecki, who is held up as the bastion of all things hip, smart, and alternative by some, is also not only virtually unknown to the wide Canadian public, hooked as it is into the mainstream through an I.V. in its arm, but also to the group who, arguably, are the zinesters of the twenty-first century. His gripe with bloggers—and their gripe with him—points to a growing generation gap between the hipsters of the nineties and the hipsters of the new millennium. The world twentysomethings live in now is so saturated with easily available personal information—from age, gender, phone number, and sexual orientation to hour-to-hour updates of their relationships, moods, and sex lives—that one more casual observation, mean or not, is no big deal.

In many ways, Niedzviecki’s work hits on why it is he is at the same time mainstream and independent, celebrated and unknown, everywhere and nowhere. In his 2004 book, Hello, I’m Special: How Individuality Became the New Conformity, Niedzviecki explored the constructs of this generation’s YouTube-MySpace mindset. The formerly independent-minded conduits, he explains, have grown into a mainstream highway to fame. On that highway are droves of desperate and deluded young people the world over, proclaiming their specialness, lining up to be the next Canadian Idol or Top Model.

The result is an “alternative” culture that is asking itself: Alternative to what, exactly? Niedzviecki argues that there is no more underground. Now, he says, “mainstream culture incorporates pretty much anything that anyone will buy, or not.” Explicit violence is mainstream, so is homosexuality, drug use, environmentalism, African aid, and gay pornography. Niedzviecki notes there is genuine creative action happening on an independent basis, but adds, “You’re fooling yourself if you justify what you do on the basis of being underground, or against the Man. In fact, in many cases you’re working to the Man’s advantage by creating a false dichotomy between underground and mainstream.”

These same ideas, among many, are woven into Niedzviecki’s fiction. Random House’s Collins says her biggest job when editing Niedzviecki is to flag the “undigested cultural criticism.” For his part, Niedzviecki explains that while his earlier fiction was “just [a] burst of emotion,” newer works are “animations” that explore how “human beings try to use mass culture to form narrative about themselves.” For him, non-fiction is abstract and even the “real people” become abstract because they are “stand-ins for an idea.” In his novels, Niedzviecki can put his abstractions into his own fictional world and see how they play out. In the novel Ditch, the lead characters are searching for a kind of pop-culture identity. In The Program, Danny tries to become a cyborg so he can control his memories, resulting in a story about using memory as a metaphor for technology and the relationship between individuality and capitalism.

Niedzviecki is a man navigating our mass culture meltdown, trying to eke out his own identity—someone who situates himself as an independent creator because he’s not dedicated to any one entity or corporation, and a writer who is unknown by many of the people who should admire him most. He is an intellectual interested in a world where people do things on a not-for-profit basis to express themselves—from backyard wrestling to collecting elephant figurines—someone who is more concerned with packaging and style than what he feels is the obsolete notion of “selling out.”

Ultimately, Niedzviecki is mired in the same problems as his characters, fictional and real, with one foot in the mainstream world, one in the independent world—both worlds colliding. Nearly a decade after being anointed, Niedzviecki is still the guru of indie culture, but now he is just one among billions, in a universe that is just as likely to turn to the “crap” as it is the “cool stuff.”