Friday. On the hottest morning so far that summer, the Stickle-McNabb was following his normal routine to exacting detail. He flirted with nearly every girl he encountered during his commute and, as always, he ordered a coffee in the shop around the corner from the office tower where he worked. His hair was unusually impressive. While riding the subway, he asked the pretty red-headed woman who was standing beside him if she’d ever had to kill anyone? With her eyes?

She stiffened and smiled the absent smile she had perfected while enduring many mornings much like this one. She exited the train at Bloor station and didn’t look back.

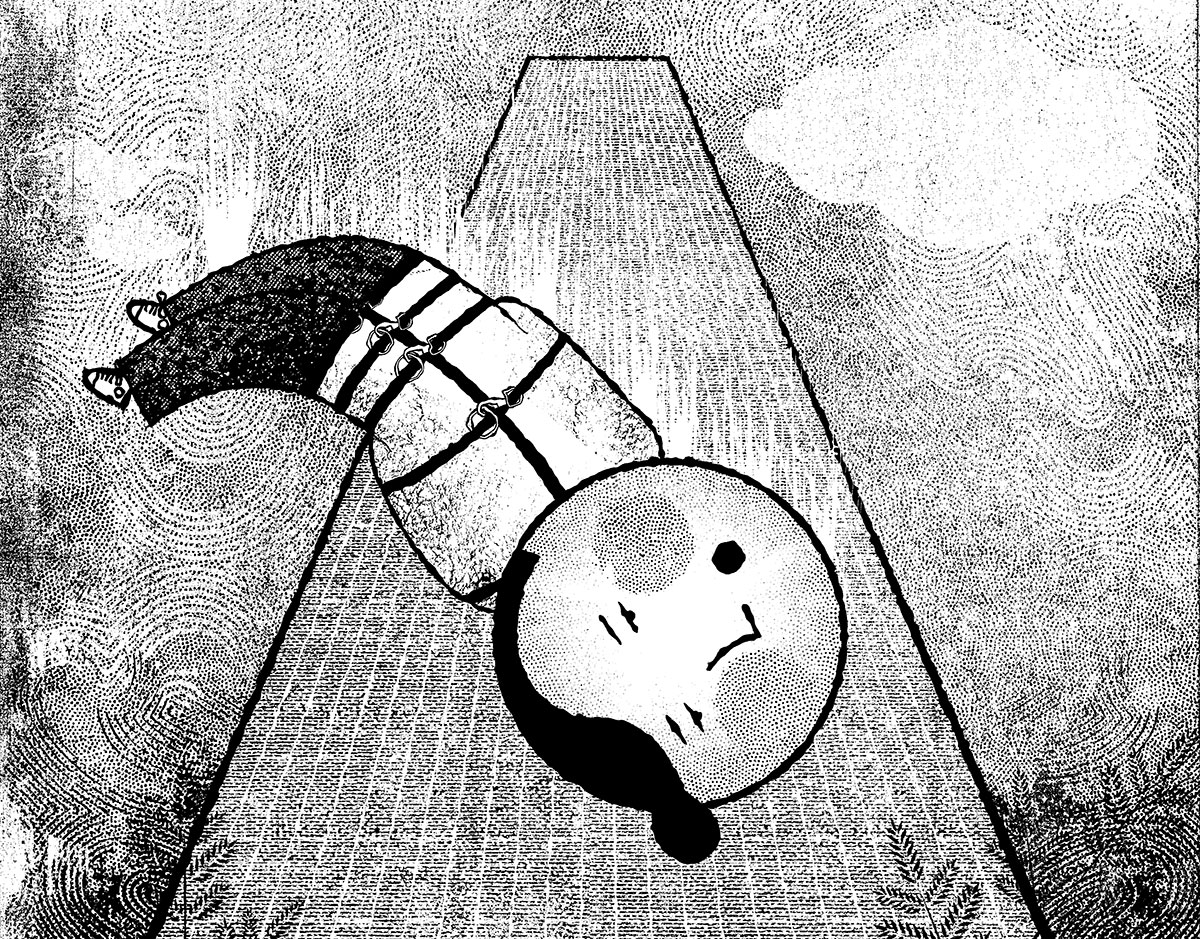

Twenty to nine. That same summer morning. Seven floors below the office into which the Stickle-McNabb would soon be strutting so confidently, a friend of his was already bent over his computer working. This friend was Jomini. He had once been a slacker so legendary, if a film were made about biblical slackers, his character would have been cast opposite Jesus—a slacker John the Baptist maybe. In the past two and a half years, however, he had changed jobs six times: once voluntarily and five times in a fashion somewhat less voluntary. As a consequence, Jomini’s confidence was evaporating like water droplets on a hot sidewalk. This encouraged a tendency to act as if he had somehow gotten himself twisted inside an indecisive straitjacket, one with second guesses for straps, and hesitation for buckles.

He jumped when his boss popped her head into his cubicle. She asked if he could join her in her office. She gave him ten minutes. He listened to the swish her nylons made as she walked away down the hall. For the next five minutes, he shuffled paper back and forth across his desk. He reorganized his pens. He didn’t leave the safety of his cubicle until he had arranged the Post-it notes stuck to his cubicle wall, first by colour, then alphabetically. It proved impossible to combine the two organizing principles. He shuffled the multicoloured paper squares as though playing a shell game. He ripped them off the cubicle wall and pasted them back up, over and over again, in a futile effort to make them fit.

An unidentified phone number hastily scrawled on red paper: does it go above the company password, written in a solid yellow cursive, or beneath? The paper mosaic he’d created seemed deliberately intended to mock him. No matter which square he tore off and where he replaced it, a new dynamic arose.

A pink reminder for next week’s departmental lunch? Where? If an answer was hidden inside these shuffles, it eluded him.

Doug made them three. A triad of warrior preppies wrapped inside a parallax of shifting perspectives, with only the tension between them holding things together. Doug claimed that even simple, widely accepted concepts such as time fell beneath his notice. Time was too bourgeois. When talking about himself, he employed terms like “Doug the Destroyer,” or “the Scourge of the Middle Class.” Modern hygiene bored him, and he rarely remembered to brush his teeth.

Jomini, the Stickle-McNabb, and Doug were travelling along similar trajectories. They were a triangulation, three distinct causes knotted around the same effect. Similar to the way highway traffic, when seen from above, appears to move in rhythm, as if following a deeply ingrained pattern. Like a stock market’s fluctuations viewed over decades.

While Jomini was meeting with his boss and the Stickle-McNabb was proceeding as always, Doug was out front of the same office tower, at the corner of Front and Yonge. The traffic was furious. He was rolling as far back on his heels as he could without falling. The office tower scraped up above him through the carbon monoxide, which clung like a low ceiling. He rolled back and looked up, and the tower veered like a stark white monolith, rows of mirrored windows puncturing its bright plastic sheen in a tightening, reversed-V pattern that stretched up into the hazy smog. Doug lost his balance and took a dizzy half-step backward. Steadying, he returned to what he had been doing: watching the traffic stop and start in impatient fits.

The day was already fishbowl-humid. A beatific smile came to Doug’s face, and he unbuttoned his short-sleeved shirt. Two cameras dangled from his neck, his unbuttoned shirttails falling loosely behind him. A nattily dressed pedestrian stopped beside him. The man looked sideways, back and forth, his eyes quickening to every angle of the streets facing him. Like a nervous lizard, he shot a fast glance down Yonge, under the low concrete railway bridge spanning it, toward the condos that rose before Lake Ontario like glass sentinels. He watched the traffic crossing Yonge stop and start in impatient fits. The pedestrian adjusted his tie.

“You ever notice,” he said with a neat smile, “how downtown sometimes feels like you’ve entered a giant bubble? ” Then he left, disappearing into B.C.E. Place’s pedestrian mall—that arched commercial palace of light and glass.

“That was weird,” Doug thought.

Quarter to nine in the morning. The three couldn’t have been further apart. At the same moment the pedestrian was walking away from Doug, the Stickle-McNabb was flirting with the petite blond girl who worked behind the register at his regular coffee shop. With a voice he deepened to an extra-jocular, athletic growl, he was saying the double-cream–double-sugar combination he liked in his coffee disqualified it from coffee status. He sipped, wagging his index finger in the negative.

“This merely qualifies as a coffee-like beverage,” he joked. The girl, the same one who served him most mornings, handed him the change from his double-double and complimented his hair. A smile lit her face like a reward.

“It’s good today, eh? ” she said. “The hair.”

Ten to nine in the A.M. The Stickle-McNabb’s thrust was more direct with the office receptionist.

“Sleep with me? ” he asked her.

She sighed. “No.”

“C’mon. Please? ”

“No.”

“Tuesday then? You don’t want to lose your chance.”

“No.”

“Great. Wednesday’s perfect for me, too.”

“Hmm…good point. No.”

Five to nine. Jomini trailed his hand along the wall as he walked to his boss’s office. He arrived late. Seven storeys above, the Stickle-McNabb was settling in for his day. He pulled a framed picture out from the leather satchel he used instead of a briefcase, walked around his desk, and removed the picture hanging on the wall. In its place he hung the new picture, blank, except for an illegible name and one badly executed doodle. It looked like an abstracted Charlie Brown being attacked by Snoopy. Stepping back, the Stickle-McNabb, after a self-satisfied pause, turned and admired himself in the other wall’s mirror. He repeats this routine at least once a month. This morning, the mirror revealed an errant hair, which he immediately patted down.

“Best one yet,” he said, looking back at the picture.

Nine A.M. Seven floors below the Stickle-McNabb, Jomini sat in his boss’s office, pictures of her kids staring back at him. She was making him wait. The Stickle-McNabb, sitting at his own desk, had his feet up and was busy deleting messages from his voice mail, a pencil in his mouth. He watched as a small bulbous airplane took off from the Toronto Island Airport. He, like Jomini, was alone.

Gum spotted the sidewalk in front of the office tower, like some odd reminder of something forgotten. Jomini had by now fled his office. His stomach felt hollow as he lit a cigarette and wondered what he should do. Noticing Doug, he waved and walked over as casually as he could. Damp sweat was already sticking his shirt to his back. Doug, who was always on about how he needed investors to merchandise the quit-smoking method he claimed to have developed, had a cigarette drooping from his mouth. He didn’t notice Jomini until Jomini was close enough to notice Doug hadn’t swabbed his underarms with deodorant that morning. Jomini tapped him on the shoulder. Doug turned and immediately began to explain something. His sentences were Joycean in their complexity. His cigarette, bouncing along to the convoluted rhythms of his speech, distracted Jomini.

“Huh? ” Jomini asked. “You’re what? Counting red S.U.V.s? Why? ”

Doug exhaled a dense trail of smoke and, turning back to watch the traffic, waved his hands excitedly, then stopped to frame a passing car inside outstretched fingers. He kept his fingers locked around it as it passed through the intersection. “No man,” he said, “art shots. Listen, per capita, Canada’s one of the most heavily franchised countries in the world.”

“Huh? ”

“It’s all the doughnut shops we got up here.”

“Right.” Jomini checked his watch. He dropped the cigarette he had been smoking and stepped on it, twisting his foot like the thing had insulted him. “It’s, like, nine-thirty in the morning, man. What are you doing up? ”

“I don’t care about time.”

That was when Jomini blurted out he’d been fired. He couldn’t hold it in any longer.

Doug’s reply was immediate. “Just now? ” He waited a second before adding, “You know what? I don’t feel sorry for you. At all. You know that though, don’t you? ”

“No, I didn’t know that. Is that some Zen thing? ”

“No, it’s not a Zen thing.”

Every management book Jomini had ever read clearly stated it was better to wait until the end of the day to fire an employee. This time frame offers them less opportunity to steal. Jomini didn’t think he was the kind of person who got fired at twenty after nine in the morning. He dismissed the notion he might be considered too cowardly to steal. He was the kind of guy who develops new business ideas, industry-embracing strategies, while telling jokes beside the coffee machine. A minimum-input–maximum-output type of guy. Not a first-thing-this-morning-must-remember-to-fire-that-guy type of guy.

Doug promised to wait while Jomini went back to retrieve his stuff. Actually, he agreed in principle, but refused to guarantee he’d stay in the event of unforeseen circumstances. Doug squinted directly into the sun, which had begun to shine patches through the day’s pollution.

“Doug the Destroyer can’t promise anything,” he said. “If something happens, it would be imperative the Destroyer leave. The Destroyer must remain safe.”

Jomini sighed. “What could happen? ”

Doug thought for a second, stubbing out and lighting another cigarette before speaking. “A fire. The Destroyer would leave if there was a fire. Flooding…snow leopard plague…a windstorm—for sure if there was a windstorm. The Destroyer hates windstorms.”

Jomini didn’t let him continue.

While he watched Jomini walk back into the office tower, Doug flipped open his cell, tapped a button, and autodialed the Stickle-McNabb. According to the schema Doug used to order reality, cellular telephony was the opposite of bourgeois. Unlike time.

Jomini slid up his building’s smooth intestine of an elevator shaft and discovered a group of guys he recognized from Institutional Sales bunched in his cubicle. A solid, square guy sat slouched in Jomini’s chair, swivelling it beneath him. He was Chinese. Jomini recognized him from the company hockey team. A defenseman, he had a face like a chipped puck. Imitating Jomini’s terrible posture as he swivelled, he drooped his arms so the knuckles of one hand scraped the ground, apelike. His laughing friends—two other Chinese guys, a Sikh, and a white guy—all hunched around him. The Sikh guy watched Jomini approach with a wicked smile. His beard made his teeth appear huge, and his black turban clashed against his blue suit. Jomini quickly scanned his cubicle. The white guy was awkward—so tall his limbs appeared elongated. The other two Chinese guys were neat with horn-rimmed glasses. Post-it notes lay everywhere. In his chair, the first Chinese guy pretended he was speaking into Jomini’s phone. He was imitating Jomini.

“Sorry, buddy!” he said. “Very busy this afternoon. I’m off to go play golf with my rich white friends.”

That wasn’t nice. Jomini tapped him on the shoulder.

“Excuse me, I think you’re in my chair.”

The group stopped laughing.

The Chinese guy swivelled and stared up at him. He stammered something.

“Can I ask why you were being racist? ” Jomini said.

The Chinese guy looked at his friends before turning back to Jomini. He tensed up the same way he would if he was lining up a corner check and the ref was busy on the other side of the rink. Metaphorical stick in hand, what little apology had decorated his face disappeared.

“You know that I’m, like, Chinese here, eh? ” he said. “You know that, right? ”

They stared at each other.

Non-telephone confrontations always made Jomini uncomfortable. But then, the Chinese guy did something unexpected: he dropped his tough-guy look. Not like gloves, but as if it were an unnecessary, redundant something not needed when it came to Jomini. He opened his hands toward Jomini, palms out.

“Hey, whatever,” he said. “Listen, man, we all heard, and that’s just tough luck.”

Someone behind Jomini chirped, “Bosses are bastards.”

Promises to drink beer were made. The Sikh in the black turban said, “So fucking what? Gives you more time for golf though, right, buddy? ” He punched knuckles with the white guy.

Jomini forced his mouth’s ends upward. It felt as if he’d pulled a muscle.

The Stickle-McNabb bragged how the summer suit he’d bought on a business trip to Hong Kong—spun by tobacco-addicted spiders in an underventilated sweatshop—weighed less than three ounces. Ear to his cellphone, he approached his window and looked down.

“What up? ” he asked Doug, and then listened. “True dat!” he said.

Doug waved and said he was standing on the sidewalk below. The Stickle-McNabb leaned until his forehead pushed against the window. A dot with an open shirt might be waving, but he couldn’t be sure.

“I can’t today,” the Stickle-McNabb said. “I’m busy. I’ve got to interview, like, three people.”

The Stickle-McNabb gave interview-ees twenty minutes to write an essay. They had to write about a two-sided print he showed them, by the Russian artist Wassily Kandinsky. Abstracted colour shots, explosive, cut through with perpendicular lines, amorphous blobs, that sort of thing. The Stickle-McNabb got the idea from the movie Six Degrees of Separation. The first thing he did after watching it was go out and buy two Kandinsky prints and glue them together, making himself a copy of the painting the movie’s high-end New York art dealers keep in their apartment. The one they flip from front to back, each side having a different, opposite abstract painting on its canvas—one side wild, the other, orderly and restrained.

Sitting the interviewees in an empty storage room, the Stickle-McNabb would inform them that, upon completion, their essays would be read over the company intercom. After they settled in to work, he would interrupt them, then again, and again, each time wordlessly flipping the print to its other side. Interviewees had cried. The Stickle-McNabb framed his favourite examples and hung them in his office, like a proud parent hangs his child’s kindergarten work.

The blue screen on Doug’s cellphone shimmered against the heat floating off the sidewalk’s chapped concrete. He tapped a button and autodialed Jomini. Jomini was on the other line with the Stickle-McNabb. The three of them conferenced their cellphones. The Stickle-McNabb agreed to take the day off. He would tell his boss he had a rare variety of summer flu. Jomini was riding the elevator back down, his arms around a cardboard box stuffed with looted stationary, cellphone cradled against his shoulder. His voice mingled with theirs as though they were lounging beside a digital oasis, where electronic palm trees swayed in an ethereal breeze. They asked Jomini how everything had gone.

“This Chinese guy and some of his buddies made fun of me is all,” he replied. “No biggie.”