The first time we see him, he is onstage, half-naked—ankles bound, legs bowed apart, wrists cuffed behind his back, chest curled forward spooning the empty space before him, neck wrapped with a thick chain, and at his throat, a padlock. Beside him a hand-painted sign promises, “THE AMAZING ABSCONDINI, GREATEST ESCAPE ARTIST EVER KNOWN! PRODUCING THE BEST ACT OF ITS KIND IN EXISTENCE!”

I eye the lock at his throat, longing to release it and taste the salty fruit beneath. I want to climb inside the chains that surround him and press against him until our bodies take shape from one another. I want to shed this skin, to release the invisible chains that bind me. In this double body, I am always torn in two directions: I want someone to gather me like night and hold me firmly on this earth; I want to fly high into the nocturnal sky until I see beyond bodies and into souls.

A dwarf in a miniature mauve tuxedo steps onstage and wraps Abscondini’s cuffed wrists with a heavy chain.

“Who would like to click shut the lock? ” he asks the crowd. A tall awkward man clambers onto the stage. Basking in the spotlight, he drunkenly clicks the lock shut, then fades back into anonymity.

The distance between Abscondini’s hands is carefully measured to preserve the illusion they are closely bound, and to allow easy escape. The dwarf escorts the escape artist to a small wooden booth, draws the curtain, eyes his gold timepiece, and waits.

I study the shoddy exterior, imagine that half-naked man struggling behind the fluttering curtain. With a shimmer of black velvet, Abscondini emerges to our applause, bows low before us, and winks.

Interior dressing room. Early evening. We watch Abscondini enter our mirror. A threadbare plumage of competing stripes brightens the glass. Puffs and pads overflow from jars; hairbrushes snagged with tangles are scattered on the flimsy dressing table; fallen underclothing lewdly glows on the floor, kicked under the table by Lily, not quite out of sight.

Abscondini approaches us with his hands extended, one for each. “I’m A-A-Alek A-A-Abscondini.”

Lily looks away, but I meet his gaze. “A pleasure.”

Abscondini invites us to dine at Le Paradis. His silence makes Lily talk even more, to fill the space. She tells him her dream of flying while I examine his silent wrists for imprints of rope and chains, something tangible to connect him to the marvellous man I have just watched onstage. I notice a thin sliver along each wrist, sealed with a perfect row of stitches. Quietly, he smoothes his suit, tugging his cuffs to cover the scars.

Abscondini sweeps away dark curls, which frame an aquiline nose, thin lips, and wildly crooked teeth that reappear with each laugh. Then he answers my question about chains.

“A volunteer snaps the cuffs around my wrists. My assistant locks me in a long wooden box. While he wraps heavy chains around the box, inside, I break free of the cuffs, using a pick hidden in my hair. With my feet, I easily push off the end of the box, which has been loosely secured with sawn-off screws.

“My assistant draws a velvet curtain to enshroud the event with mystery. The orchestra plays Wagner. At the climax of the piece, I rattle the chains, for effect. Then I draw open the curtain and emerge, hands held high. Slowly, I walk around the stage three times and bow. I am always looking for volunteers.”

We remain sitting at the table long after the crowds have gone. When she thinks I am asleep, Iris covers my face with her grey scarf. I drift off into the darkness. In my dream, Iris and I fall from a high cliff, free for an instant and fearless. Then we plunge into a deep pool. Hands grasp our legs. I kick hard, trying to rise to the surface. The hands pull me deeper.

I take a breath: water. Iris cries and the pool becomes deeper. Murmuring voices approach. We stand mute before the large bodies.

“Nothing special but for that hip,” a voice says. Father is at the table drinking whisky. Mother turns her back on us and walks toward a bright light.

“Please don’t go,” I say. Without a word, she vanishes into the light.

I sink deeper into the pool. The Amazing Abscondini plunges underwater in a coffin. I open my eyes. My lashes press against the rough surface of the scarf. Who am I in this darkness?

In The Everyday Life of Side-show Freaks, Professor Humboldt Fogg wrote, “Iris is the evil twin, while Lily embodies all that is good.” If there is evil, it is also in me. If only you could see through my eyes, you would know what I am hiding.

When I cast off the scarf, Alek smiles at me. Then he looks into the mirror and meets Iris’s eyes. I wait, because that is what I have learned to do.

Sunday morning, Iris presents me with the following set of rules:

- You will remain silent Mondays, Wednesdays, Fridays.

- I will pass the day reading, and will not speak on Tuesdays, Thursdays, Saturdays.

- Sundays we stay together.

- On my days, the world exists for me, and me alone.

- On your days, I surrender my will and allow you to go and do as you wish.

- Do not speak unless you are spoken to.

- Never, never interrupt.

- Do not fidget.

- On my days, I decide what we wear. (Please note: if you select frilly white, I will insist on crimson satin.)

- Please, please do not make loud noises while I am in bed.

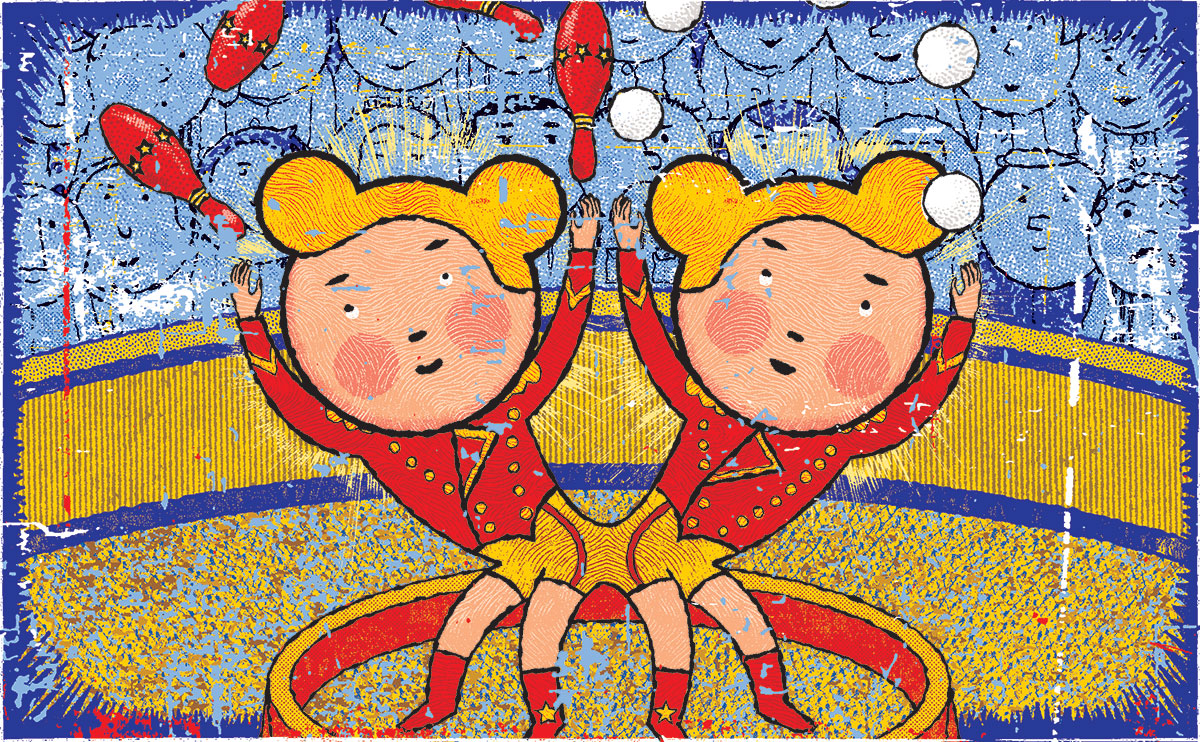

“CHAINED FOR LIFE.” In the newspaper photograph, I juggle bowling pins while Iris tosses small white balls. The audience forms a circle around us, revelling in our hip. I close my eyes. Beautifully alone, I drift into the most peaceful sleep. Iris wraps her arms around me and holds me like I am a child. Our guardian, Mrs. Hutton, enters our trailer and cuffs Iris on the head.

“That stumble of yours spoiled the act. You stupid girl. Who do you think you are? ” Mrs. Hutton tugs at the grey sweater that clings to her like a second skin. She needs us to make her living and we could turn on her at any minute. “I never had the opportunities that you girls have. You don’t know how lucky you are.”

I rise to the ceiling, which presses down hard upon me. I want to disappear. Instead, I remain above, compelled to see everything.

I don’t pretend to understand anything. All I want is to fly. I am learning to live with the family that haunts me: a mother who abandoned me, a father who does not know I exist, a guardian who pushes me onstage every night against my will, and a sister who will not leave me alone.

“Do you love me? ” Iris whispers. I could embrace her now, as she did me not so long ago. Instead I whisper, “No.” I want to cut these chains that bind us, this persistent umbilical chord. In response, Iris cuts her arm in intricate patterns with a small knife until it becomes a bleeding work of art. It is the only way she knows how to feel, the only way she can release her pain. I want her to surrender to me, a spirit guide lodged deep within. If only I had said yes.

I lean to the side while Alek straps Iris into a straitjacket. How easily she surrenders. As he binds her, she tells him stories.

“We were once asked to leave a train for travelling on one ticket. We were once asked to remove our dress to prove that we are one. We were once fired from a double-barrelled cannon.”

He does not mind if what she says is untrue. As he binds me, he begins to tell stories of his own. The soft timbre of his voice washes over me and I, too, am no longer concerned with truth.

“Several years ago, I went to do a show in Saint John, New Brunswick. I had always wanted to visit Canada. The few who turned out for the show were largely seamen and were unimpressed by my act. After the show, I wandered through town. I didn’t see much, on account of the fog, but I did catch a glimpse of the Reversing Falls and the insane asylum high on the cliff above.

“I wandered up the driveway and explained my business to the doctor, who wanted to know why I chose to escape underwater and not on land. He began to speak excitedly about the death wish and invited me to dine with him. We drank plenty of whisky and ate our fill of lobster, and the gentleman agreed to give me a tour of the asylum the following afternoon.

“It was like nothing I had ever seen. People sat in a large room: some stared at the walls, some rocked back and forth, some played cards at a large table. The doctor was a curious fellow. His hair was a shock of dishevelled grey, and he stooped over like a hunchback. When I asked about a woman who sat staring at the bay, the doctor told me the story of a woman who had jumped into the Reversing Falls, in 1842: ‘Her petticoats filled with air as she descended and kept her suspended on the surface of the water. She was whisked over the rapids and shocked into sanity.’”

“Maybe she was just happy to be free,” I say.

Alek tightens the straps and continues. “At one point in the tour, the doctor took me past a heavily bolted cell with a narrow grille on the door. Inside the cell, a patient desperately struggled to escape from a straitjacket.

“I had never seen such a restraint. The jacket was made of canvas with an opening at the back, and the sleeves were fastened behind the man’s back with leather straps and metal buckles. As the patient struggled to free himself, he thrashed against the wall and fell to his knees. The more he struggled, the tighter the straps dug into his flesh.

“‘Only a madman would attempt to free himself from such a restraint,’ the doctor said. I begged him to give me one of the jackets. The doctor seemed intrigued by my request and agreed to give me one if I could successfully free myself from it. He tightened the sleeves around my back with buckles and straps. Once he had me bound very tightly into the jacket, he locked me in a padded cell and observed me through the grille. For hours, he watched me as I struggled to remove the garment. Finally, I collapsed onto the floor, exhausted by my efforts.

“Eventually, I managed to use my teeth to loosen the buckles on the sleeves. Then, I undid the other buckles through the canvas and twisted out of the garment. Once I had removed the jacket, the doctor turned the key and opened the door.

“‘For that,’ he said, ‘you deserve three.’ He went to a cupboard and handed me three jackets to carry about for the show.”

As Alek speaks, Iris struggles to escape. Her writhing only draws the straps deeper into her flesh. The intensity of feeling heightens her love. She wants to feel deeply, even if what she feels is pain. I am looking for a different story, a love that is easy, a mother who cared, a father who wept, someone to forgive.

The midway is littered with paper cups and scattered popcorn on the muddy paths between rows of sagging stalls, bent frames, torn awnings. Even the recently acquired ball toss is mud-splattered and cigarette-burned.

The clown’s faces, each with its own perfect tear, create the impression of rain. Tumbleweeds of sugar spun to cotton drift by. To avoid a syrupy puddle, Lily pulls us sideways. Mud squishes between my toes and under my sandaled feet.

Through the dangle of prizes hanging from the roof of the ring toss, I see Abscondini, on his knees, wrap a chain tightly around his chest, breathe deeply, and burst it apart.

A heart could do that.

Mistake No. 341: Ask him about his past.

“The first time I fell in love was with Bess. She joined the circus as my assistant, but she was too sensitive and was prone to fits of sadness. She missed her family, from whom she had never been separated. When I stayed out late, I would come home to find her wearing only the ruby red shoes she wore for the show, crying, and sharpening our knives. She began to chew her nails until her fingers bled.

“Bess became famous as the Woman Who Gets Sawn in Half. People said that we were joined at the hip, that without each other we would never survive, that we completed each other somehow. They didn’t see how jealous she was of me.

“During our act, Bess climbed into a wooden box. I closed the lid. She thrust false feet (wearing identical ruby red shoes) through one side of the box and pressed her body tightly into other side. I sawed through the middle, cutting the box in half. Then I drew a curtain, recited a magic chant, and opened the curtain to reveal her standing in her red shoes, which shone like blood beneath the hem of her white dress. Soon, she began to wear those shoes to bed.”

Abscondini lifts the bedcovers and reaches for my naked feet. When he enters me, I open my eyes to find him looking at Lily. “Oh baby,” he says.

As I gaze at the faltering candle, the tangled clothing, and the thin man I am about to lose, I am consumed by the irrepressible hope that, one day, he will love me as much as his grief.

That night, the Woman Who Gets Sawn in Half masters a new trick. She wires Abscondini, “I have just thrust one hundred knives into my wrists. Come quick.” That night, Abscondini leaves us without a word. With her, he was always the Strong Man.

With me, he is weak.

Saturday. My day.

We sit at a Brooklyn lunch counter. I am eating a salad. Messily. For me, lettuce is never elegant. Translucent dressing drips like milk down my chin. Iris sits at my side. Observing Rule No. 2, she is silent.

When we leave the café, I see Alek. He has come back for tonight’s show. He returned on last night’s train after discovering the Woman Who Gets Sawn in Half in bed with the Knife Thrower.

“I want you to join my act,” he says. “The dime museum has two sections. The exhibition hall displays freaks and curiosities: midgets, giants, fat ladies, bird girls, dog-faced boys. The variety hall is for shows: magicians, jugglers, clog dancers, puppeteers. We could do a double bill: the Amazing Abscondini, assisted by the Two-Headed Girl. You would always be at my side.”

I have lived my entire life in someone else’s shadow.

“Do you love me? ” Iris whispers to him. Alek smiles at me apologetically and turns to her. I close my eyes and vanish, grateful to Iris for saving me. Even if I wanted to, I don’t know how to love without an end in sight.

I want to chain him to the bed, to know he is mine, if only for an instant.

“Do you really think you can hold me? ”

“I’d like to try,” I say.

“What do you think, Lily? ” Abscondini asks.

She looks up from her romance novel. “I think she wants to try.”

My fingers brush blue velvet and steel. Cold metal turns in my hands as I remove his most recent acquisition, regulation handcuffs, from a wooden box lined with blue velvet. I tighten one cuff around his wrist and the other around the headboard. I snap a second pair around his free wrist and stretch his arm to Lily’s side of the bed. Then I bind his feet.

When I straddle him, I bring her with me. She leans against the wall and pretends to look away as I push my fingers deep into his thick hair and remove the pick he promised not to hide. He defends himself: “In the world of illusion, there are no lies.”

“The cuffs are too tight,” he complains. Earlier, he said I could close them as tightly as I wanted. He’s just angry that I found the pick.

“Admit you can’t do it and I will release you.”

He is silent. Lily tries to hand the pick back to him, but I conceal it in my own hair.

He speaks to me like I’m a child, insists I unlock him, “immediately!” But I refuse. Without surrender, love is impossible.

Lily reaches into my hair and places the pick in his hand. He opens the lock, unshackles his feet and walks away. On the dusty path, splinters of a broken mirror capture our reflection. We don’t know it yet, but this is the last time the three of us will be together. Already, I feel the chains loosening and myself slipping away.