One of a group of about eighty demonstrators who marched on the U.S. consulate in Toronto, backing civil rights workers in Alabama, is heaved into the crowd by police, on March 16, 1965.

On March 16, 1965, Torontonians took to the streets in reaction to and support of the U.S. civil rights movement, which had taken a dramatic turn just days before. March 7th became known as “Bloody Sunday”—the day that “good trouble”–causing activist and future statesman John Lewis led more than six hundred protesters across the Edmund Pettus Bridge, in Selma, Alabama, marching for improved voter registration rights for Black Americans. State troopers used tear gas, clubs, and whips to attack the protesters, igniting a wave of shock, outrage, and sympathy across the United States.

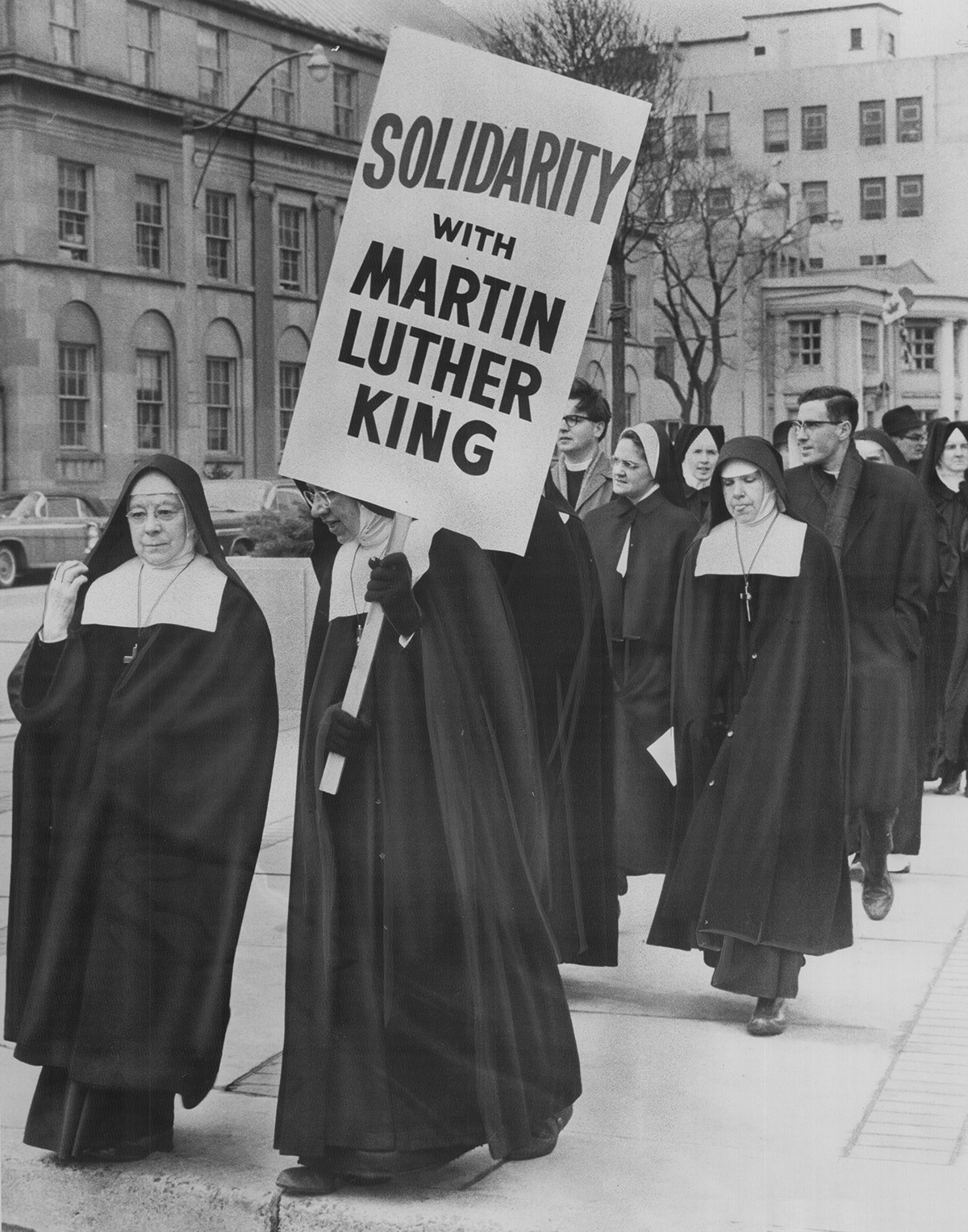

Those same emotions wafted across the border, as Canadians followed the stories coming out of the South. So, on March 16th, Toronto protestors showed up both for their American neighbours and for Canadians who could relate to the same struggles around race and belonging. Nuns marched down Queen Street, carrying signs proclaiming solidarity with Martin Luther King, Jr., while police tossed students off the steps of the U.S. consulate, on University Avenue. Toronto refused to be silent that day because, despite what is popularly thought, this country’s history of Black activism has always bucked against the oft-held archetype of Canadian politeness.

In 1971, Yale professor Robin Winks released a book, The Blacks in Canada, that was intended to be the pre-eminent historical tome of Blackness in the country, from the sixteen-hundreds to present day. Among other things, Winks stated that Black Canadians “wanted nothing more than to be accepted as quiet Canadians” and were “unlikely to organize militant, noisy, pushy protests.” Near the end of 2020, it is not uncommon to hear the same fallacies—an assumption that racism “isn’t as bad” here as in the U.S. and that Black Canadians don’t have—and have never had—any reason for rebellion.

The practice of the enslavement of Africans tainted these lands, but resistance was part of the story as well. Peggy Pompadour was an enslaved woman jailed for escaping from her owners (a practice historians called “slave resistance”) and was held in Toronto’s first jail, in the late seventeen-hundreds, on the site where the King Edward Hotel stands today. Around that same time, an act of resistance by another enslaved woman named Chloe Cooley created a historic shift. Upon realizing she was being put on a boat on the Niagara River to be sold to a new owner in the United States, Cooley raised hell and fought with all her might. News of her struggles eventually reached Colonel John Graves Simcoe, the lieutenant-governor of Upper Canada, who used her story as the catalyst for the creation of the Act to Limit Slavery in Upper Canada.

Viola Desmond never set out to be an activist on the day she refused to leave the whites-only area of a Nova Scotia theatre in 1946, but her act of resistance pushed forward conversations around racism in Canada.

In more recent times, Black Canadian activism has had a number of important lightning-rod moments. In 1969, Black students launched likely the most important student protest in Canadian history after raising issues with discriminatory treatment by a professor at Sir George Williams University (now Concordia). And after a spate of shootings of unarmed Black men by police, in particular that of Lester Donaldson, Black activists in Toronto founded the Black Action Defense Committee in 1988. The B.A.D.C. pushed the provincial government to create Ontario’s Special Investigations Unit—an overseeing body intended to stop the unjust process of police prosecuting, and acquitting, police of violent and racist crimes.

Future history books will tell the stories of Black Lives Matter—how it went from a hashtag to an organized movement—but Canadian history books should not continue to ignore the activism that has taken place within our borders over centuries. These stories, and many more, prove that Winks’s theory of the docile Black Canadian was incorrect, and that the Toronto protest on March 16, 1965, was birthed from more than sympathy for our rebellious neighbours. Canada has been shaped by rebellion of its own, and Black Canadians have always driven their own self-determination and self-preservation, by any means necessary.

Police look on as about two hundred and twenty students stage a sit-in and sing freedom songs outside Toronto’s U.S. consulate, protesting violence against Selma’s Black population, on March 10, 1965.

Nuns bearing placards were among three hundred clergy who marched down Toronto’s Queen Street to the U.S. consulate in protest, on March 16, 1965.