Ben walks the streets, his hand ducking back into his pocket, always wanting to reassure himself that the knife is there. Inside more private moments, he would sometimes take it out and play with it. On occasion he notices something new, the newspapers covering that store window, the small sign announcing that it would soon become something else. Almost as though a place can cocoon. But more often the streets seem like shifting patterns of old. There is always so much old, he thought. If you are new you are creeping into the world. It was up to him to be the pin, to hold something down until it happened, and this time he might actually succeed in making a difference.

There is a thump and people look. Two cars have bumped each other, a gesture that would almost look loving if it weren’t for the expression on the face of the young man stepping out of one of the cars, a brown Jeep. The young man takes a look and says “More damage to your car than mine!” He gives a giggle and hops back into his car, pulling away. Ben’s hand goes into his jacket pocket and his fingers find the knife once more. He slows, but picks up his pace again.

Little birds, if I had bread for you, you’d get it, Simon thinks. Small sparrows and chickadees appear near the bench, hop around, and shotgun away, as if moving to invisible currents.

Today at the bookstore, Simon had moved slowly, his mind like an anchor. He turned to his co-worker Lisa and asked, “Do you ever have the feeling that something’s wrong but you don’t know what it is?” Before her response came, they waited through a layer of silence.

“No. No, I can’t say that I have.”

Simon walked into the receiving area in the back and dropped the same question in front of Veronica. She was new to the store and he found her to be quiet, mysterious, and beautiful. She moved her hands in a way that was tired and yet showed she was completely unaware of their elegance.

She looked at him. “Something’s wrong but I don’t know what it is? I feel that all the time.”

Simon asked Veronica out. During the first drink they had together she explained about literally running from her office work, packing up and deciding to try life in another city.

Now, in early evening, he kicks his feet, tries to unwind and get the new little seeds out of his mind. Watching the birds. The woman he’d helped today was about forty-five, well dressed, and dipped in perfume. She looked as though nine people had spent the morning working on her hair. The hair was a tidy bun of blond as if ready to unravel and give birth to something Simon didn’t want to know about. It was one of those days that Simon didn’t want to be there, and one of those customers who needed to hold hands with an employee.

“It’s all alphabetical by author, so the man you want is right here.” He starts to walk away.

“Now the difficulty here is that my husband needs the one he doesn’t have.”

“Oh.” And how am I supposed to help you with that? Pretend to be interested, pretend to be interested. There is one hardcover next to six paperbacks. Titles like Death Learns the Tango.

“You could take the hardcover, that’s the latest one, so he may not have it, and it could be returned if—”

“Yes, but I need to know. I need the one that I need. I have the one I need written down here somewhere.” She begins to go through her pockets, purse, and bags for long minutes while Simon thinks about what he could be doing. She pulls out a tremendous wad of money. “Oh, that’s not it.”

If this isn’t an American tourist, Simon thinks, I’m moving to France.

Another stretch of silence hits bottom with the woman saying, “Oh, I feel so terrible.”

And so you should, you incompetent woman! Do you think I have nothing better to do? The words come up and hit the back of Simon’s face, but he does not say them. Simon the bitch. He thinks around for something to say, despite really having nothing to add.

“Ah, well, that’s O.K. The books will be here.”

“Could you just write down all the titles so that I can compare them with what my husband has?”

Why, of course. Simon returns from his terminal a minute later with each title on a scrap of paper. More for her cyclone purse.

“And could you put the phone number of the store on it?”

Why, of course. Another minute, another scrap.

“All right, thank you. I’ll check with my husband. We don’t have much time. We’re just over from New York.”

Ah, yes.

The first day that Simon had worked in the bookstore they put him on the information desk and everyone else left. He hadn’t even had a tour, so he tried to tell people where the washrooms were by looking on a map of the store along with them. People almost blocked out the rest of the store sometimes, so many of them approached the desk. For the first few days he kept a copy of The English Patient nearby, reading sentences between customers the way other men might take constant sips from a flask. That was two years ago. Simon liked bookstore work, to be outnumbered and surrounded by books, like a good army. But for God’s sake—something new, anything. Ben had been teaching him some of his skills, at least. Somehow, stealing appealed to Simon because it felt like experimentation, stepping outside the rules of your own life. The important thing was to steal from those who had too much, to steal in an ethical way.

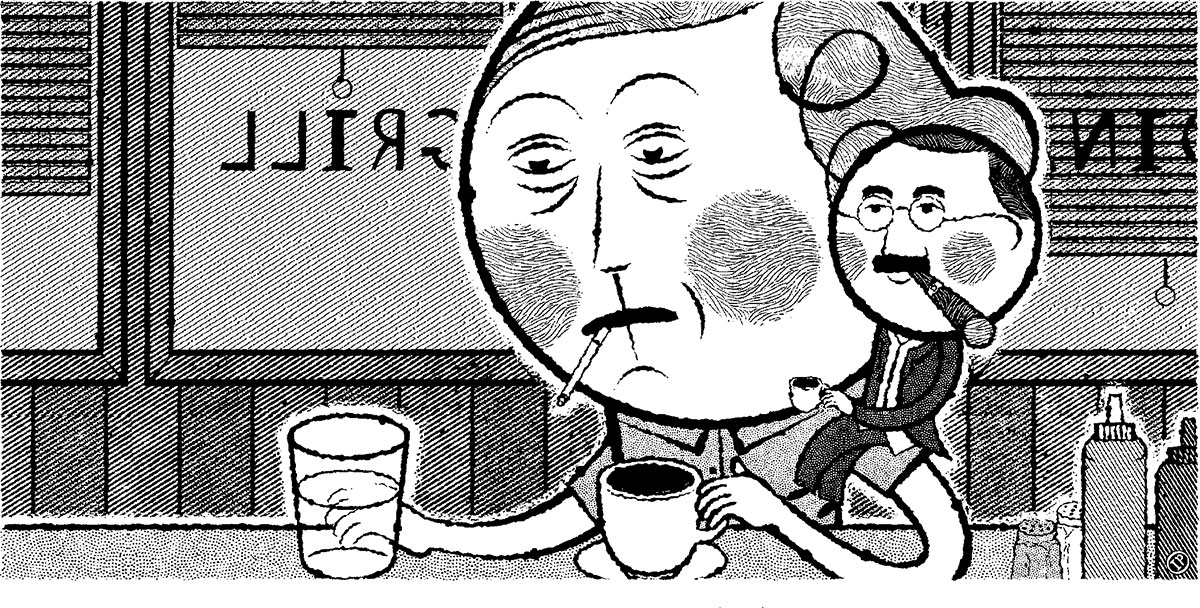

It’s early evening and Ben is sitting in the No. 1 Spadina Street Grill, in his usual booth. He imagines a finger in his ribs, watching Poke slide into the booth. Ben never got around to asking him why the finger stab was his usual greeting. Somehow, it was simply who he was, never any other name. He remembers Poke looking up, brushing dirty hair out of his eyes, and ordering the all-day breakfast as always, whatever time it was. Poke and his stupid jokes. The other people in his apartment building called him Catman, he was so quiet. What drove him to suicide? Stupid pressures, growing like cracks in the ice he stood on. Why is the world no different now?

When he had first heard of his death, Ben turned the fact over in his mind, looking at it from different angles. He had concluded that when somebody harmless is removed from the world, there is no guarantee that an equal amount of harm is removed. Worse than no guarantee, there is no sign of it at all. On a quiet night in his apartment, Ben stood up from his kitchen table, opened a drawer, found the sharp knife with the solid handle. He walked the few steps over to his jacket and slipped it into the pocket.

Simon adjusts his napkin and silverware. “Nineteen-seventy-seven,” he says, “was the year we lost humour.” He raises a finger. “The year that Groucho died.”

“And you think,” Ben answers, “that you can . . . tap into that?”

“Of course! The past can inspire the present, ignite it.”

“I don’t know, Simon. Sometimes I feel like I’m still trying to put the past out, you know what I mean? I mean it’s fine to appreciate what was . . .”

“It’s still there.”

“All right, it’s still there, any old work of art. But do you have to have such . . . intensity?” Ben has trouble finding the words, the image of the past spreading like a hot sun over a new day, melting it into a desert.

Simon looked over his shoulder again at the old woman, Helen. Helen always waited outside until every booth was taken and then came in and asked to share with someone so that she could talk. She listened also, which people said was rare anywhere, and at each comment brought a hand down to slap the top of the table and say “Oh!” or sometimes laugh, throwing her head back to reveal her crooked teeth. She would look out the window to find words and then string them together, sentences as delicate as cat bones. Old Helen had been in Toronto for thirty years, but was still “not quite used to it, you know.” The waitress would walk away when Helen was just beginning to say the words, the same thing she always wanted. The first time Ben had been nearby he was startled at how rude he thought it was, until Helen had been brought her coffee and glass of ice water. “Oh, you’re a dear girl.” The rumour that interested Simon was that she’d once been involved with Groucho Marx.

“You are not even going to try and sleep with old Helen, Simon. If you even try to take advantage of that dear old lady I will punch you in the face,” Ben says.

“All right, all right,” Simon laughs. “You act like I’m some handsome calf who just gets whatever the hell he wants. Obviously, I’ve never told you about some of my former attempts at romance. Hey, do you know what Groucho Marx said when he was asked ‘What would you do differently?’ in an interview shortly before he died?”

“No.” Ben actually feels a little happy.

“He said, ‘I’d try more positions.’ It’s true!” Simon laughs again while Ben considers calling him an idiot.

There is a way that Simon pictures laughter. On the air all around them, so that you can reach for it, or you are bumped into it somehow. When Ben thinks of laughter it is something that managed to break into the world, a plant making its way through a crack in the sidewalk.

Ben’s thoughts go back to Poke. He had been told his last words, that Poke had lifted his head from the hospital bed and said “Something’s wrong.” Ben remembered his father’s last words—he was very weak, in a hospital bed and drifting in and out of consciousness. When the phone rang, his eyes opened and he said, “Who’s on the phone?” before closing his eyes and eventually drifting away and dying. It seemed odd, or maybe just interesting, to Ben that his father’s last words carried no significant meaning. He inquired about what was probably a wrong number, blissfully unaware that he was speaking final words.

Poke was a man who asked for spare change all day to see the nearest movie that he hadn’t seen before. His strange habit was ordering a large Coke and popcorn even though he was standing at the back of the line and it would be at least five minutes before he was served. People would stare at him as he calmly and repeatedly said, “A large Coke and popcorn, please,” until he finally got up to the counter and swallowed, simply staring at the man behind the counter. Under that new pressure he would pause, then finally get it out. Seeing a film was an added bonus, and a good film was even better, but what Poke liked was the relief, the dark folding over him for two hours and the great doorway to somewhere else on the screen.

It was Poke who told management about “the weasel,” his nickname for the greasy man, about forty-five, who would sail down a row of the theatre and sit next to a woman. It didn’t matter if there were lots of empty seats around. Then he’d lean in as far as possible so that the woman would have to squish to the other side of the seat to avoid him. Whenever a woman got up to move, he’d find another spot a few minutes later. Poke couldn’t go so far as to confront the weasel, but was satisfied watching anonymously in the darkness while an usher stepped in and leaned over the weasel, spoke to him, and then escorted him out.

The door outside the No. 1 Spadina Street Grill has the word please over and over again in small cardboard signs running almost all the way down the glass to the doorknob, where there is another sign, lift latch, then pull on door. Even so, Ben and Simon sit and watch one person after another walk straight up and pull repeatedly on the door.

In the background, old Helen can be heard asking the couple she’s sitting with about her husband: “He died of cirrhosis of the liver—what’s that?” There is a quiet delay while they mumble that they don’t really know, and then the man is optimistic enough to offer, “Well, he sounds like he was a nice man, your husband.”

“Why would you say that? He drank a lot, you know.”

Over near the door, the cash register is beginning to sputter and whine. A man and a woman are standing impatiently while the owner tries to convince it to co-operate, flicking switches and trying again.

“Did I ever tell you why I gave away my book of romantic poetry?” Simon asks.

“Uh, what?” Ben turns back to look at Simon.

“Nice book, you know? Thick hardcover, expensive—the professor I had for romantic stuff was named Hornby. Starting his class, I’d heard some nasty things about him. The man was a thousand years old. He started the English program at my university. He taught me in his very last year before retirement. There was a sign posted near the offices for the English department that said to sign the page if you wanted to be able to continue to benefit from the wisdom and experience of Prof. Hornby. Under that someone wrote ‘join the prof. hornby club and get an a!’ Anyway, I liked the man, despite how abrasive he could be.”

“How? I mean, what did he do?” Ben asks.

Simon pauses. “This is one thing I saw. After a comment this guy made, Hornby turns and states to the rest of the class, ‘Now, whenever you see his eyes light up, that means he’s beginning to get it!’ But he was also full of these great remarks, like, ‘Don’t treat anything like it’s the gospel. In fact, don’t even treat the gospel like it’s the gospel.’ It’s true that he also used to drool into his grey beard, but whatever. I liked him. In fact, he was one of the few teachers where I’d stay after class and walk him out, just because I was sincerely interested in what we were studying and in talking to him. I wasn’t one of those eager, kiss-ass types, you know?” Simon makes the word kiss-ass snakelike, uses the first letters as little stepping stones to enjoy the sound of the letter “s.”

“Oh, no,” Ben says. By now four people are waiting over by the cash register and the owner is giving it gentle smacks and making stupid jokes to try and help the situation. Ben is trying to keep his mind off the distraction while Simon talks.

“Those types used to ask questions just to demonstrate their knowledge, and they’d come to class and set up a spot with little datebooks spread out in front of them—so much stuff that half the time I thought one of them was going to pull out a potted plant. Anyway, I don’t think Hornby wanted to be nasty; he just didn’t have the patience some days. But if you approached him and spoke to him, he was O.K., you know? He used to make more harmless little jokes than nasty ones, often grabbing at our personal characteristics. ‘How do you get your hair like that, Simon? It probably takes a lot of effort to make it look like you just got out of bed.’ He was so old that I had to walk slowly with him, just like I do with my dad. Part of me even felt that I had the conversations with Hornby that I wish I could have with my dad. We discussed faith, life after death, these kinds of topics. And he listened.”

A woman in the cash register lineup steps forward a little. “You know, you really have to get your act together with this register, this is just ridiculous.” Ben is still facing Simon, trying to ignore her, at the same time thinking, What a stupid way to phrase a complaint. A second later, a man jumps in with, “Yeah, this is getting a little irritating.” Ben leans in to be able to focus on Simon.

“So, one day, I go to class, the second last week of school, and I’m tired, lots of work to do. Suddenly, Hornby is firing all these questions at me, one after another, dropping all around me like shells. And I’m so tired that I didn’t get a chance to read the poems I’m supposed to be able to talk about. So he’s asking me things like ‘How does the mind of the poet change from the beginning of the poem to the end?’ and I haven’t even read the fucking thing. But he doesn’t let me off the hook, keeps going back to me and nailing me to the wall, both of us so disappointed and offended. Only once did I have some kind of response, when the discussion began to cover belief in an afterlife. He turned to me and asked, ‘Do you believe in God?’ and I said, ‘You mean after the last twenty minutes?’ It got a laugh, at least. After class, the worst of the kiss-ass boys approaches me to say, ‘Oooh, you got burned, bad,’ and all I could say was, ‘No kidding,’ and walk away. Hornby had announced that the following week, in our last class, I was to come prepared to lead the discussion and take it somewhere. I was to ‘demonstrate my ability.’ Can you believe that? After all the free time I spent after class talking with him, he demands that I ‘demonstrate my ability.’”

Simon stops because both he and Ben are distracted by the noise at the door. The man behind the counter is now calculating the bills by hand, writing them out with the help of a calculator. The man is saying, as if for the second or third time, “Look, sorry, all right? This isn’t the kind of thing that happens very often, usually people are a little more patient.”

“Oh, well I guess it’s just me,” one of the men says. “I guess everyone else waiting here is really enjoying themselves.” The complaining man turns to look behind him for support and a woman helps him with, “Oh, yeah. This is great.” The man behind the counter is clearly angry, but goes on writing the next bill.

Over in the booth, Simon asks Ben, “What do they think, that he planned this?” He pauses. “And worse than that, don’t they have this in perspective at all? There are parts of the world where you are shot at, you know? Or where you don’t have any fucking food, never mind the luxury of . . .. But not here in Canada, where we’re flustered if we have to stand in a line for a few precious minutes.”

“Nothing,” Ben says.

“Sorry?”

“Nothing has ever happened to them.” Ben takes out his knife and places it on the table next to the plain cutlery. The knife with the solid handle doesn’t look like anything terribly different. He spins it around so that it makes a circle, takes it, and puts it back in his pocket. He stands up and looks at Simon. “I’m going.” Ben begins to walk towards the cash register and the people.

“Wait, Ben. I’m coming. Let’s take the back door. I have something I want you to see.”

“The back door? But we have to pay the bill, I want to go over to those people there.”

“I’ve paid the bill. I mean, I’ve left enough. Let’s get out of here, Ben. I have something I want you to see.”

Ben looks down at the table, sees that Simon has dropped a twenty-dollar bill there. He feels a slight tug in the direction of the back door, notices that Simon has curled his arm around his, snug and tight like a chain link.

The same night, in rows of packaging, canned goods like tin soldiers, Ben is looking around, shopping slowly, reaching for things he doesn’t want, drunk with distraction. It wasn’t often his thoughts could push something out of his throat. He decides to put something back, turns to Simon: “You insisted that we leave.”

“Yes. I think I had an idea of what you were planning in there. Would you have done it? Which of the people, and where would you have stabbed?” A strange kind of curiosity fills Simon.

“I don’t know exactly. I had the idea of racing by and slashing, maybe writing a letter to a paper so that I can explain. Being a kind of decency terrorist. Or maybe really finishing one off for Poke. Someone who gives off a kind of stupid heat, burns with stupidity, with ignorance.”

Ben gets his bread. They wait to get up to the counter. “Pulling yourself into knots isn’t a way to live, enjoy anything,” Ben says.

“Yeah. Ironic. I served a woman at the store once. She’d had to stand there for a minute first and I said, ‘Sorry for the wait.’ Know what she said?”

“No.”

“She said, ‘I enjoyed it.’ I wanted to ask her how she became such a remarkable woman, but I didn’t really get the chance.”

They get up to the counter and the food is punched up on the register, but, instead of his money, Ben accidentally pulls an old phone number out of his pocket, says “Oh,” and hesitates a second. It is an old number, useless. The cheap hotel where his friend Poke had the money to stay for a few nights after some old man gave him a fifty-dollar bill.

Simon jumps in with, “What my friend here means to say is that he wants to pay for the food with this phone number. It’s a good number.”

There is a small curl, the beginning of a smile, on the face of the young woman. “Um, I don’t think so.”

“But you know, this could be a valuable number. I mean this could be a real friend, you know?” Simon’s eyebrows go up and he tilts his head a little. “O.K., I guess this is one of those places where you just take money.”

Ben finds his money and they pay. He doesn’t say the words Simon, you can paint on blank things. At times, you are my voice.

Crossing the bridge, Simon stops to admire the view. It is a fresh night and the air feels healthy and good. In the dark, the trees are moving and thinking in the wind, hushing the earth with a quiet voice. Simon steps over and leans on the thick stone railing and Ben comes over to join him. Not far below, the concrete path winds its way across the grass in the park.

“So, what happened when you went back?” Ben asks.

“Where?”

“When you went back the week after, to lead the class in the discussion and try and impress Hornby, show him your stuff or whatever.”

“Oh, that. I remember sitting there before the class started, obviously nervous, while Hornby made remarks like, ‘Well, I hope you’re ready.’ One woman who I’d spoken to before was kind enough to give me a little wink. I did all right, I thought. I moved fairly comfortably through a comparison of all of the odes by Keats. The discussion puttered along and then finally picked up and got into the air.”

“And? What did he say?”

“Well, I didn’t catch him in the classroom, so I went to his office and said, ‘I hope I’ve redeemed myself in your eyes somewhat.’ He turned my own expression back to me and said, ‘Somewhat.’ Can you believe the bastard? As part of an excuse to explain why I hadn’t necessarily always spoken in class, I told him that I had worked hard to break out of a pattern of extreme shyness. I mean, walk seven miles rather than have to ask the bus driver how much I owe, that kind of shyness. Even having thrown the shyness off I still wasn’t in the habit of talking in class. He told me that ‘believe it or not’ he’d been really shy all through high school and I resisted the urge to say, ‘How lucky that you’ve had this chance to take revenge on whoever you want for an entire career as a university professor,’ but I didn’t. Somehow it wasn’t the way to say goodbye. Anyway, that’s why I gave away my nice hardcover book of romantic poetry.”

At least a few minutes pass before Ben says, “You know how different people can be inside things? Can represent things?”

“Sure, that’s what I’m talking about.” Simon looks down to see that Ben has the knife in his hand, shining slightly in the moonlight. Ben puts it at the edge of the stone railing so that the handle is over the edge and he is holding down the blade with one finger. He lifts his finger and the weight of the handle carries it over the edge and it falls with a gentle thump into some of the tall grass below. Another long pause.

“You’re . . . all right with that?” Simon asks as they start to leave.

“Oh, yeah. Or at least, I’ll try it out.”

“So you could be back again, pulling up long grass by the roots, looking for that goddamned knife?” Simon laughs.

They are leaving the bridge on the far side when Ben asks “Hey, do you think you could get that book back from your friend? I mean, just explain that you need to be able to drop it off a bridge, right?” Simon found a way to his open, crisp laugh years ago and it’s a sound that comes out now, into the night.