I am feeling much better. I am finally feeling ready to work.

So I have found this quiet room in my club—I have come back here, having avoided it for a few despairing months, largely for fear of seeing a woman who did not want me—and I find it is perfectly friendly and safe and indeed largely empty today, which is fine. I will slowly re-enter the world of friendly facades and frequent accomplishments and easy discussion of those accomplishments.

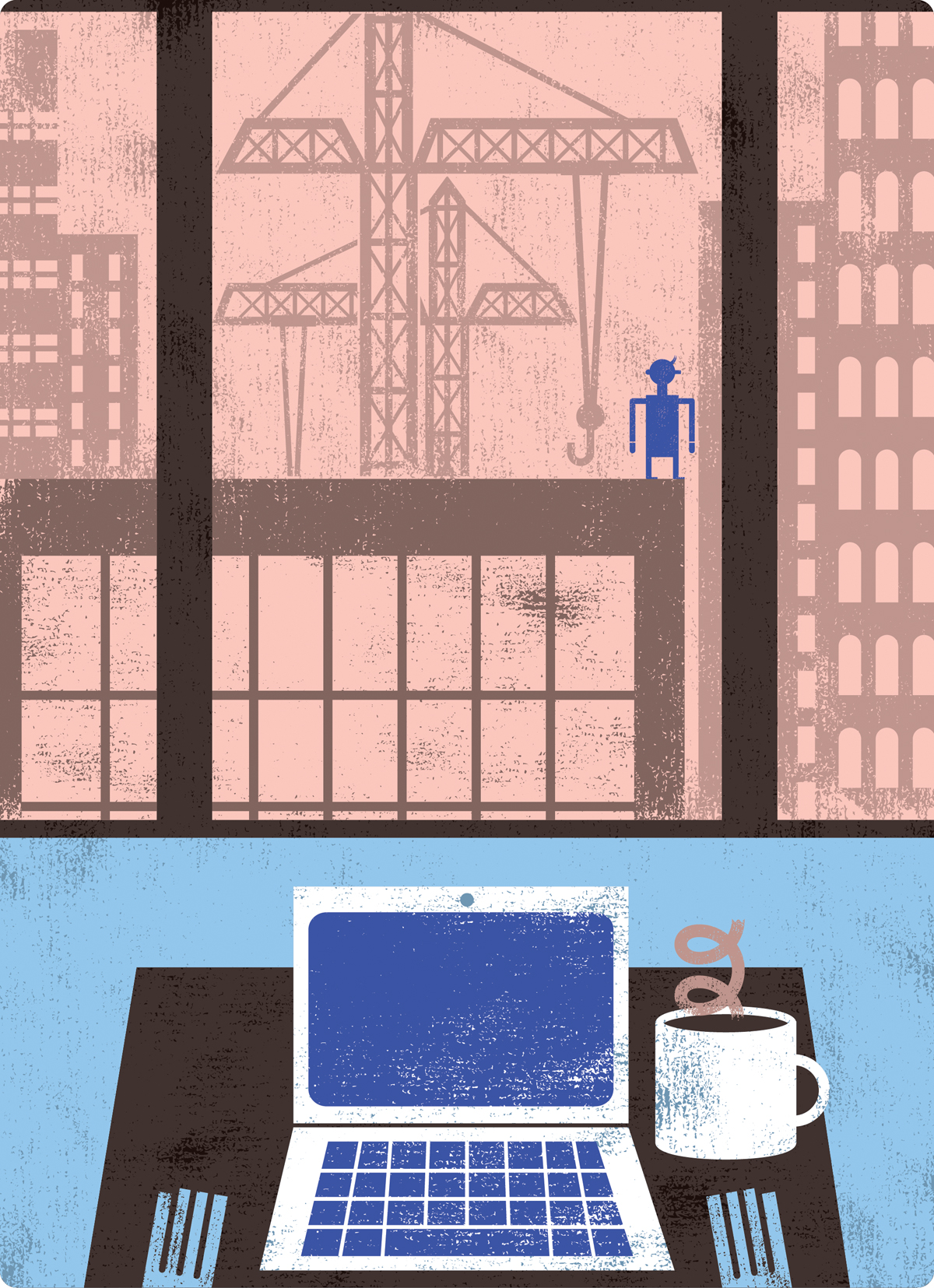

And I find it is so pretty, on a sunny day in here, so high up above the deadline-conscious street (all the stores seem to be about to close all the time in this city; one has only minutes to complete, whenever one tries, a day’s worth of errands, but perhaps this is due to my inability to foresee, from the darkened confines of my apartment and the enervating fluorescence of my screen, the day elapsing as quickly as it does, which is itself part of the condition I must start, in all honesty, calling an illness. A condition or illness I am glad to feel has dissipated and is slipping away like a suit of heavy clothing). So pretty the great window is like a screen. The screen frames the top of a building under construction.

What do I see? The slow swing of a crane against the sky. The sky is a rather anemic blue, which may be due to some light-resistant, energy-saving property of my club’s glass. I wouldn’t be surprised if it were that, a flattening effect carelessly included by some insensitive environmentalist, so proud of his energy-saving ugliness. But this is the kind of irritability I will be able to resist today.

A man on a rooftop alone. The building is new and square and empty. It is made of white concrete and glass. Its roof and corner are all I can see of it from this window. Since there is nothing in it, you can see right through. There is nothing behind it but pale blue. I have a buzzing beep in my ears. It is a beat made by computers.

The man looks disoriented. He is just standing there. Someone dropped him high up there, maybe from that crane, and he doesn’t know how to get down. He is standing up there for all of us, the summit of humanity, defiant against the sky.

I am assimilating these various pleasures: the bright sun, the empty reading room, the sudden warmth and colour after so many weeks of rain, the fresh coffee on my tongue, the cool, clean bumping of this beat in my expensive headphones. And the waitress who brought me my coffee is lovely: she is long-haired and slim and arched and soft skinned and soft eyed and soft spoken. She is the feminine against this efficient cool room and precise music. She is the focus of all my longing now, all my lust, all my desire for sensation and images after the winter.

Sometimes physical pleasure is all it takes to dissolve a conviction that there is no such thing as a livable life. Sometimes a bright empty room is all it takes to open the brain to perception, to allow consciousness to actually occur.

I admire the engineering of the crane, its hard geometry, its economy of movement. Its leisure. It is deliberate and precise. I admire its majestic sweep. I am enjoying admiring these things. It is as if I have been asleep.

I could not appreciate this in my cramped study, with its papers and bills, its telephone with its angry blinking red eye. So I shouldn’t feel guilty about the ludicrous cost of a single coffee and the indulgence of a glass of sparkling water in this excessive place.

Out another window, the humped back of the sports stadium reflects a white sheet of sun. It is sleeping.

All the glass condo buildings refract and reticulate light, a city of prisms.

I am actually relaxed. I will not think now about a woman who did not want me. I am happy to be alone. I am happy to enjoy these pleasures in confidence, without that ridiculous feeling that pleasures I cannot share with her are hollowed of their value, not even pleasurable at all. That is the sense I have had all winter.

That was the darkness of winter. I am in light now, and can enjoy the world without her. I can focus my lust and longing and yearning on this beautiful waitress, for example.

Imagine if I were still with that woman who did not want me—imagine if she had wanted me, and I was still with her, and had woken up with her this morning. I would feel guilty about my lust for the lovely young waitress. I would feel trapped and stifled that I could not pursue her, not even consider talking to her, asking her how long she has worked here and where she goes to school. I could do that right now. I am free to do it. I am free to live in a world of sensation and conquest. I should be extremely happy about this.

I have not seen the waitress for a half-hour. It was a young man who came to check on me and my coffee just now; he must have taken over this room. So I have possibly missed my chance to talk to her. She must be working the dining room, which by now probably is filling up for lunch.

It is also possible that she has a boyfriend, or even a husband. Or that she would be hardened to the men who come to this club—all the men my age, ten or fifteen years older than she is, with the confidence of careers and money, although in my case the money is more of a way of speaking than a reality—all the men who smile and ask her, somewhat condescendingly, if she is a student and how long she has been working here. She might see me as something quite embarrassing: a somewhat dull businessman going through some sort of mid-life crisis. She would joke to her boyfriend, who is an artist, a painter who works with wax, about the slimy well-dressed characters who hit on her all day long.

I am tired thinking about this. I do not want to compete with them. I do not want to be associated with them. Perhaps it is best if I just admire the waitress from afar.

I will not wonder if the woman who did not want me is also still alone in life. It is completely irrelevant. It has nothing to do with me. She did not want me because there is something, undoubtedly, closed in her, something tight and protective and restrained and ultimately crazy. She is probably incapable of love. I would not even want to be the man she is with, if she is with a man.

I should be working on my essay.

I am here to work on an essay about architecture and democracy. I do not really have any views on architecture and democracy. Unless it is simply that architecture is profoundly undemocratic.

There. Done. I would like to submit that—to the absurdly overconfident non-tenured sessional instructor who commissioned it for his comically earnest and pious and almost unreadable quarterly—and get paid something for it. Something a great deal larger than that that has been promised.

I would like to write instead about women and architecture. About how the world is made up of beautiful things, and even the most clean and geometric and minimal of architectures exists to house the waves of brown hair on this waitress’s neck. (Where is she?)

That there is no sense to architecture without women.

My coffee is cold and I must find the washroom. I will leave my computer here and hope that it is safe.

The possibility that troubles me is that that woman, the one who did not want me, may be with another man and love him, actually love him and give herself to him the way she did not want to do with me. This should not make me sad, as it has nothing to do with me, or with this lovely room and interesting music or the ideas that I must translate into words.

I really have to pee.

On walking back from the lovely, cool marble washroom, I passed through the dining room and saw the rare tuna salads and the glasses of white wine and I began to feel hungry. It would be easier to eat than to write. I wonder if I should have lunch here. I have not made a reservation, and it is really too expensive. But if I save this document and pack up the computer and walk out into the sunshine to find a hot dog or a sandwich, it is unlikely I will come back. I will end up in a park, smoking a joint.

I realize I am melancholy now, and that this melancholy is dangerous and I am now long past the darkest days of winter when I thought and threatened those crazy things—the humming light and tan surfaces of the doctors’ offices seem like a foreign country now—and so this melancholy must not be allowed to develop, must either be extinguished or illuminated for what it is, a black fungus growing. It’s amazing how quickly this happens, how the shadow of melancholy will bloom into a cloud. Perhaps I am just hungry. Perhaps I am just missing the waitress.

For it could be the waitress—really, it could be anyone, anyone who comes to save me from loneliness.

There, I said it.

And in fact, now that I have said it, let me admit, that it is not sex with the waitress I want. I had sex with the woman who didn’t want me. She would have been happy to go on having sex with me, I think. Just not very often, and only when she wasn’t busy.

I do not want a woman who does not want me. Nor do I want to be desired by a thousand women and have my choice of them and treat them as coldly and distantly and carefully as she treated me. I do not want that revenge. I simply want there to be someone—not here, in this moment, for I am enjoying this solitude, this clarity—but someone somewhere else, possibly working too, somewhere else, possibly thinking and writing similar thoughts, but aware of me, and eager to see me later, and to hear what I saw and what I wrote. I want to be connected to someone by an invisible and infinitely stretchable elastic band.

I was not meant to be a carefree seducer of waitresses, or of women generally. I am not good at conquest. I do not want either to be that solitary human high atop the empty building, with the grid of streets like canyons below him; I do not want his sense of triumph, of giddy clarity, if it means being alone up there. He is pacing back and forth now, as if agitated.

I suspect he is talking on the phone, describing what he sees.

Things aren’t any good if you can’t describe them to someone. And I don’t just mean write it down—I mean describe it to someone who listens and says, Yes, I heard what you said, I am with you.

Now I must finish this essay, and in order to do that I must be on my own, and in order to do that I must have lunch, on my own, and I must appreciate the beauty of the sunshine and the quiet and the sense of the city’s confidence, its streamlined majesty, and the almost unbearable poignancy of the unsharableness of this beauty, on my own.

This is good work.

The man on the building top has waved his arm angrily and thrown something off the edge. His phone. This is a stupid gesture, I could have told him, and one that could cause devastating injury. I hope it landed on a ledge below.

Close to the great window there is direct sunlight that will make me and these carefully cleaned and pressed clothes damp within minutes; that is another discomfort that will upset this equanimity and so is to be avoided. I should be in my chair working anyway.

The man has swung a leg over a sort of temporary railing or scaffolding that must be part of the construction process and is now standing on an unprotected ledge. He is braver than I; I would be afraid of a wind sweeping me off. But he works in this field; he is atop tall buildings all day.

He is still gesticulating although no longer holding a phone. Who is he shouting at? The sky?

Now he is sitting on the ledge, his feet dangling over.

And so now here it is again – this sweaty unwanted pressure to act, to engage myself, to leave my computer and my headphones, a pressure that comes at a person at every second of every day and that can be overwhelming, even paralyzing—that pressure that I am not quite ready, after the winter I have had, to respond to and that I thought would be avoided at least here in this expensive quiet and privacy. And with the pressure of course comes the guilt that one is so inept at responding to pressure. All this is to be avoided.

(Possible new essay title: “Architecture and Engagement”?)

The man’s building is a few stories higher than mine. He is at the very top. Below, I can see the street, the trees, the fire hydrants quite clearly, and I can tell who is female by their walk and hair but the bodies are too foreshortened to distinguish identity. In this part of town, down there, on such a lovely spring day, they would be the kind of person I know or used to know, people I would greet happily and kiss and even flirt with. I will be that person again. Now they might find me thinner, sallower, older.

(Title: “Architecture and Solitude”?)

There is a clatter of voices from the room next door, the dining room. There must be people standing at the windows. So there is no longer pressure on me to alert someone; the action has been taken from my hands. I am now, firmly, observer rather than participant.

Sure enough, it is a couple of waitresses, mine and a bursting busty one, their backs to the impatient businessmen, their faces close to the window, waving their hands as if anyone could see them through this environmentally resistant non-glass. It would look just like a mirror from outside.

From behind her I can study the inviting tightness of the new (spring season?) uniforms. They are not really uniforms but fashionable skirts and blouses as designed by an admired homosexual. They change every season, which must partly account for the absurd inflation of our membership fees here. (I can write those fees off if I continue to do some freelance work here and there; hence “Architecture and Democracy”—and I should put “work” in quotation marks as well.) The skirts are stretchy, the blouses silky, everything is tight and confining and revealing, although horizontal bra straps are the only distinguishable undergarments. How hungry I am for some suggestion of underwear, some visible echo of it in such a highly clothed enclosure.

I am much more stimulated these days, tortured even, by round women than by slim ones, I don’t know why, perhaps because of my feeling of general weakness. Why should fat in women suggest (to me, in my neediness) kindliness? Perhaps because it makes me expect admiration, devotion, a helpless sense of unworthiness on her part that would make me loved, always loved, no matter what I did? (Essay subject for Xpel or Popsych: “Corpulence and Compassion.”)

The man is quite still now, looking down.

Some vehicles have assembled on the street below: a fire truck, now two. There must have been sirens that I couldn’t hear because of this super glass, this anti-human glass. The scene is a screen with the sound off.

Now there are police cars and the usual slow barricading of the street with motorcycles and apparently angry officers. Soon there will be the spreading of yellow tape, the brandishing of megaphones. Armed men will be on their way up the stairs now. The man has only a few remaining minutes of this gravid solitude. He must be aware of the vividness of the sky, the hysterical brightness of the sun on the concrete. All things I can’t quite feel to be vivid from here.

I feel I should feel so much for this man that I should be reciting poetry (“For many a time I have been half in love with easeful Death”?) but I feel no emotion except a curious envy. I wish I were experiencing those colours, the sharpness of the lines, the cold wind under my jacket (it is definitely too warm in here), the feeling of action, of taking action.

I have been told, by all those compassionate young doctors mostly, to think of my work as a form of action. They were so kind, but they were too young to have known failure. And when your work is largely inseparable from lusting after disgusted waitresses it doesn’t feel like action. My work is inaction itself. I would rather be pacing atop mountainous buildings.

All I can hear now are the excited voices from the dining room. Everyone must be at the window now, united and classless in their gleeful compassion. It is distasteful somehow.

The man stands, dangerously, unsupported. He is still too far away for me to make out his age, but he is slender and dressed possibly in a short leather coat, so, youngish. I bet he is a real-estate guy—how else would he have access to an unfinished building? And since the bubble burst surely the only reason to build these mammoths is to have a place to throw oneself from. What a petty problem, money.

But perhaps he is angry at a woman who does not love him.

It occurs to me that my little phone, in my breast pocket, is also a camera, but I have never taken a picture with it and would have to fumble for some seconds before finding the right button. But doing so—talk about distasteful!—would once again involve me in the action, make me a participant, and that is not, never, for me.

The floor vibrates slightly: a helicopter darkens the screen for a second, then flashes out of sight. It must be quite noisy out there now.

He sways, his arms stretch out. My heart rate is increasing, but not with fear, not with anxiety, with hope. I hope he jumps. Only one of us can jump. He at least will not be afraid. We are all afraid to jump.

The back of the room, out of the sun, is cooler. I find I am sitting again, and my back is to the window. My heart rate had been faster than I was aware, I suppose, and I grew breathless. Perhaps this inability to watch something beautiful is indeed fear. And revulsion—for some reason I am cold now, nauseated. I need more and colder water.

That harsh high inhuman wind up there, how hostile it must have felt.

There are no shouts or gasps from the dining room; the tapestry of voices is still no more than a murmur, so the crisis has subsided. Perhaps representatives of authority have arrived on the unfinished rooftop and put an end to the pristine perfection of the man’s vista, brought back the banality of responsibility.

The room is quite cool now. My computer still shines the pure unwavering light of dissatisfaction, challenging me to impose my will on it.

It is quiet now. I can hear the thin loungey music from invisible speakers again. The squares of light from the windows are unperturbed. The grey screen before me invites reflection. I am surprised to feel relief, relief at my insulation. It is not a cowardice to enjoy insulation. Insulation permits me to feel this painful and pleasurable solitude much more keenly, and perhaps express it to God knows who—someone, eventually—with much greater precision than I would be able to attain in some piercing wind, in wailing hysterical outdoor light. Imagine, that audience, that angry authority at your back, those sirens coaxing you to act! Much better, in fact, to be alone.

The fleshy waitress, all humid powdery scent, is leaning now into my space, asking if I want anything, and I can tell her with relief that I do not. I prefer to be alone. This is good work.