April moved into their new apartment—a ground-floor peppermint-green tomb—without Jared, who was finishing law school in another city. They had decided they would live together once Jared graduated, and found an affordable sublet one semester early.

To handle Jared’s absence (she soon discovered her life was dull with him subtracted from it), April bought a cat, which she named Marble. Now her arms were covered in scratches—the deceptively severe kind, pink outward from the edges. In spite of this, April had grown very fond of Marble. She had taught herself to think of Jared less.

Unlike Jared, April had never had firm career plans. She’d been applying for temp jobs until a plan emerged (which it never seemed to do), but this still did not fill her days. When the cat was asleep she engaged in private, silly games for amusement. She had begun naming objects around the apartment. She named the faucet. She named a jewel-encrusted sofa pillow. She named a turquoise hairbrush and the ice-cube tray.

There was a man who lived in the apartment across the hall from her. April gave him the name “Dean Handsome.” She had only ever exchanged neighbourly platitudes with Dean. His real name was probably something as plain as “Pete” or “Jim.” She decided he must be a lonely, sensitive bachelor—a man with heaps of love to give.

April was returning from the grocery store when Dean Handsome entered their corridor, no doubt returning from some equally banal errand. They smiled in fractions before disappearing into their suites. As April set her bag of groceries down she said to Marble, in an affected voice, “Did you see? That was Dean! We like him. We like Dean, don’t we? ” She stroked the cat and thought about Jared. She had never been apart from him for this long; she counted the days in her head to be sure.

“Should we call Jared? ” she asked. Marble was still, perched on the arm of the sofa. April reclined and said, “You’re right. We probably shouldn’t bother him.” She fell asleep to the wind issuing in from an open window.

When April woke up the sky was dim and her cat was gone. She wandered into the kitchen, driven only by hunger, briefly forgetting Marble even existed. She sat on the counter and ate cold macaroni and cheese from the fridge. Jared called an hour late. April told him she’d overslept, and he teased her for not having much to be tired about, making sure to call her “baby” every chance he got. She reciprocated, hanging the word at the end of each sentence like a decoration: “I miss you, baby. When are you coming home, baby? ”

The macaroni stuck together in gooey clumps.

“Oh, shit,” she said, hanging up the phone.

She took a tin of cat food from the cupboard and filled Marble’s dish with wet meat.

“I’m sorry,” she called. “Please forgive me. Dinner’s ready! Forgive me? ”

She walked back into the living room but Marble was not there either. The window was open, and even the smell of her had fled the apartment.

Any memory of her conversation with Jared faded. Calls merged together; lack of shared experience had made each one indistinguishable from the next, and Jared refused to bore April with the one thing that now inhabited his mind: tax law. This is not to say the conversations were indifferent. In fact, both of them tried very hard to muster genuine interest. The result was usually a conversation fraught with disguised sadness.

April cursed under her breath, and, having searched every corner of the apartment, got down on her knees to check underneath the claw-footed bathtub. She blew a wisp of hair out of her face. She cried in a quick burst, which lasted three seconds, and then changed her mind.

The next afternoon a tap on the shoulder startled her as she was locking her apartment door. It was Dean, from across the hall. “Jesusyouscaredme,” she said, turning to face him.

“Are you O.K.? ”

“I think I locked my door three times,” April said. “I don’t know what’s wrong with me.” Then she began to cry—the wrinkly, ugly cry no one was supposed to see but her.

April and Dean Handsome were in a coffee shop. They had known each other for half an hour, and twice now his leg had grazed hers under the table.

“When was the last time you saw her? ” he asked.

“A couple of hours ago, before I fell asleep.”

A sudden shame bubbled up. This fact had crept up on her: Dean Handsome was an actual human being, with ears, and a voice.

Between her apartment door and the coffee shop they had not said much; they hardly knew each other and April was embarrassed he’d seen her cry. He asked simple questions and she answered them without flourish or elaboration. She admired the stubble on his jaw—Jared never could grow a beard, no matter how hard he tried.

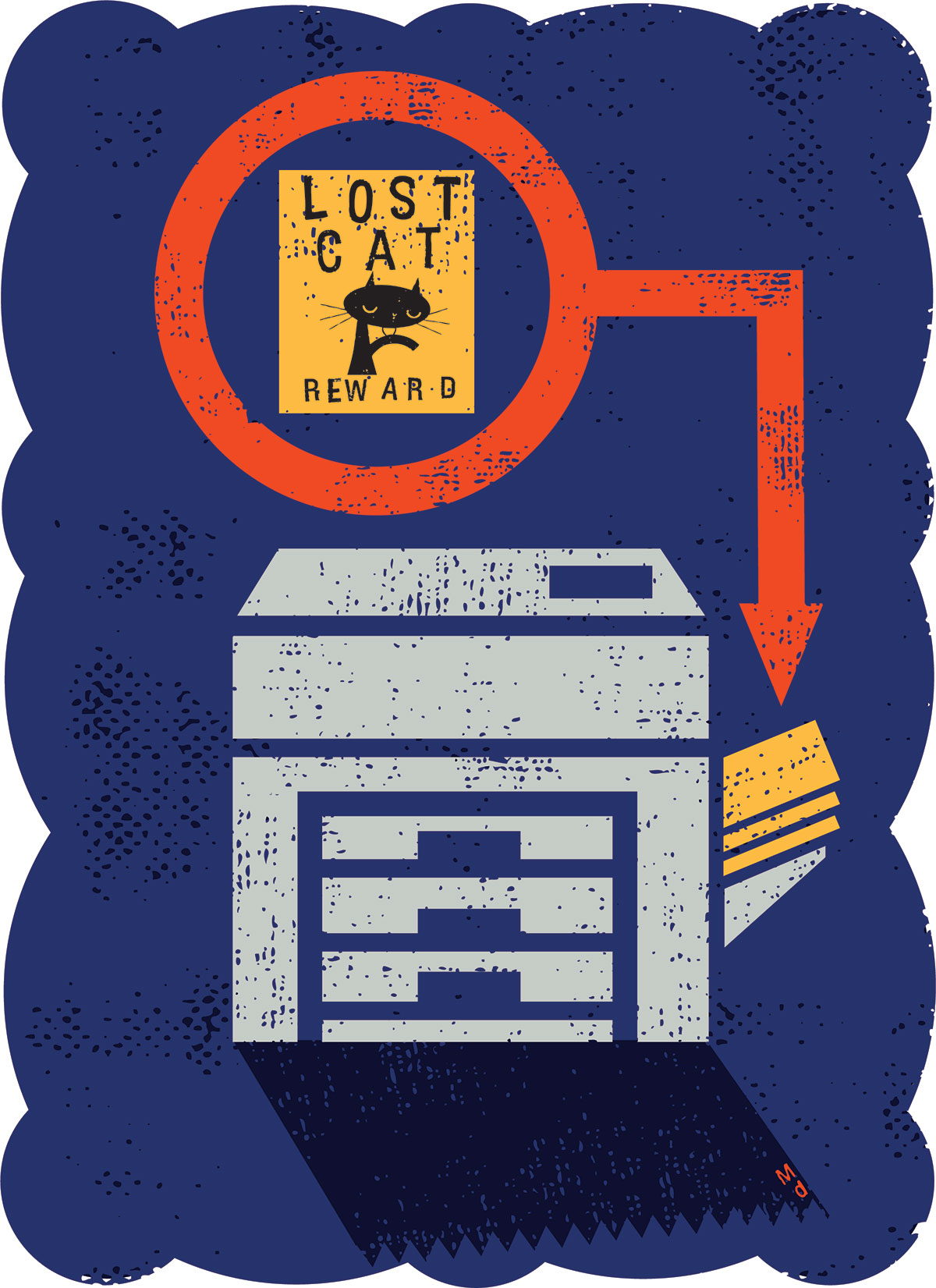

Dean suggested April find a photograph of Marble, which wasn’t difficult. She’d only taken one, a Polaroid from the afternoon she’d brought her home. It was streaked and purplish, but it would do.

“If we don’t find her,” Dean said, “we can make one of those corny flyers.”

Sensing April might panic at this possibility, he added, “Merely a precaution.”

But they hadn’t found Marble. They scanned the parking lot, and the garden that wrapped around the perimeter of their building. They looked up into leafy treetops and in other less reasonable hiding places, like the inside of a newspaper box, only because these things happened to be there, and you never know. Then it had started to rain, and they took refuge in the coffee shop.

“Don’t worry,” he said, “we’ll find her. We’ll go to a copy shop and make a flyer on fancy coloured paper: honeydew melon…or dandelion…”

“Those don’t sound like colours,” April said. She hadn’t expected to be aroused by his voice, and found her imagination—in some remote corner—willing him to continue: champagne…almond butter…sand dollar …

“You really miss her,” Dean said, drawing his own rather simple conclusion from April’s inwardness.

There was one other person in the coffee shop, and the only background noise was the folding and smoothing of his newspaper pages.

“I don’t suppose I miss her yet,” she said. “I will, yes.”

“You’ll be O.K.”

“I’m lonely,” she blurted out.

They grew silent and beyond Dean’s shoulder the newspaper crinkled briefly.

“Can I tell you something? ” he asked, nearly whispering.

“What? ” April said. “You actually hate cats? ” She laughed artificially.

“About a year ago my wife disappeared.” He took a breath, allowing a pause for this unusual news to register. “She vanished one night,” he continued, “and I haven’t seen her since.”

April was silent. Dean concentrated on something in the distance, perhaps a technique he’d developed after frequently retelling his story.

“My wife was a private woman,” he said, as if this were a disease. “There’s just so much I don’t know.”

“God,” April said. “I had no idea.”

“She kept to herself a lot, never talked to me about her work—I guess at some point I stopped asking. She had friends I never knew about, women she took classes with. Pottery, or yoga. If only I’d met them. Some nights I stay awake trying to remember their names: Dana? Alison? Eleanor from aerobics? Other times I have trouble just remembering what her nose looked like.”

April touched her own nose without realizing it. Then, she tentatively put her hand on Dean’s hand, before finally withdrawing it altogether. Dean rubbed his eyes with the heels of his palms and said, “Sorry, this is what happens when I open my big mouth.”

Dean knocked over his cup accidentally. April sopped up the coffee with napkins and Dean scrubbed at the stain on his jeans, both of them diligently attending to their tasks, as if to compensate for the swell of relief. By the time he returned from the restroom it had stopped raining. They left the coffee shop, and the gravel outside was like slime under their feet.

The next afternoon was gloomy. April worked on her résumé and thought about Dean. She was surprised, given the acceleration of their friendship, that she hadn’t seen him yet today. She did things to distract herself from the thought of knocking on his door: she pictured Marble licking the exhaust pipe of a motorcycle a block away, in the hollowed gutter of a tire in a junkyard, in the corner of a garden shed in the suburbs.

When Jared called in the evening he asked about the cat.

“Any luck? ”

“No,” April said. “You don’t have to ask every time you call, you know.”

“I’m just concerned.”

“I’ll find her. It’s not a race.”

He cleared his throat and said, “Tell me about your day.”

“It was fine. Uneventful.”

“You didn’t do anything? ”

“Not really.”

“You didn’t do a thing? ” he asked, frustrated.

“Jared,” she sighed, “I guess, maybe I did. A man with one arm came up and fixed the faucet in the bathroom.”

“The super only has one arm? ” Jared said. “Why didn’t you tell me that before? That’s something. You see, that’s the sort of thing I want you to tell me about.”

“O.K.,” April said, exasperated. “I’ll be sure to update you on the details of our super.”

“No, it’s not that.”

“I have to go to bed,” she said. “Goodnight, Jared.” After settling under her duvet April realized it was only eight o’clock. She shut her eyes anyway.

That night, a conversation in the hall woke April. She slipped into her sweats and tiptoed to the front door. It was midnight and Dean was paying a pizza delivery boy.

“Hi, neighbour,” she said, closing the door behind her.

“Do you like double cheese? ” he asked, as a curl of steam escaped from the box. She agreed to join him for pizza and a beer. In her sweats April felt more at ease. She was keen to learn more about the character she had once drawn so flatly in her imagination.

“Avocado,” she said. The tab of her beer can made a crisp pop. “I went with avocado. For the flyers.”

“Let me help put them up,” Dean said, ripping two slices of pizza apart.

April thanked him, and then they were silent.

“You know, you don’t have to do any of this,” she said. Dean merely swatted the air to convey it was no bother.

They had a few more beers and talked mostly about ordinary things until eventually the conversation became an exercise in omission, each of them editing their significant others out of memories, telling stories without the central character. Then Dean said, “A lot of people think maybe my wife left me deliberately. Lydia wouldn’t do that.”

“I didn’t think that,” April said.

“We were good. We were doing O.K.”

April raised a can of beer.

“To Lydia,” she said, perhaps just to hear herself say the name.

Dean raised his can but couldn’t look April in the eye. He swallowed as if his sip contained a hard lump.

“I’m sorry,” she said. “I didn’t mean to upset you. That was stupid of me.”

“I shouldn’t be happy,” he said, and got up to pour the rest of his beer down the kitchen sink. He emerged moments later and said, “I think I’m drunk.”

“Me too,” April said. She thanked Dean for the pizza and returned to her apartment.

The next day, April and Dean spent the afternoon together. They used glossy yellowish tape to stick pictures of Marble to concrete posts, though April hardly thought about her cat. For the first time she could envision herself being unfaithful to Jared. She imagined everyone was fated to cheat, but only some were afforded the perfect circumstances.

There was flirting, bracketed by stretches of silence. April had Dean apply tape where she was too short to reach—she relished the moments in the canopy of his arms. They stopped for a break in the playground of a public school.

“I haven’t been on the swings in years,” April said.

“Your cat,” Dean said. “Do you think she’ll turn up? ”

“I’m not sure any more.”

April didn’t mention Dean’s wife, but the question was there and she deserted it, walking over to the slide. She took a seat on the yellow lip.

“I’m glad I met you,” she said. She breathed out through her nostrils. Her eyes connected with his and expressed some urgent desire. Dean reluctantly touched the waistband of her jeans. He hooked an index finger underneath. April nodded. He unbuttoned her pants, yanking them down to her thighs.

There was the illusion that she was Lydia, April suspected—an illusion so brittle a noise or gesture could fracture it. She was conscious of the colour of her underwear, of the various properties of her pubic hair, hopeful that her body could be anonymous and aware it didn’t matter in the end. She tensed as he inserted himself. Though she’d expected he would avoid kissing—“This is how men cheat,” she thought to herself—it was still a surprise. Dean looked around: the playground was deserted, and fifty yards away a couple was playing tennis in a well-fortified court. He hunched there, inside her, and did nothing. In that moment April felt the weight of his body hovering over her, and beyond that: discomfort, moistness, breeze at her ankles. His penis became for her an annexed organ, a vague shape pressed in against other shapes, still as a kidney. Until he just pulled it out, and in the distance, a tennis ball popped.

April spent the following day alone. She ate semi-sweet chocolate chips from the bag. She lay on the sofa with her arms folded across her chest, and despite the silence in her own apartment, heard nothing from across the hall. Sometimes her thoughts turned to Dean. Mostly she thought about herself. But by afternoon her heart was quickening to the sound of doors opening and shutting, a sound that confirmed Dean still existed.

A day passed and nothing much happened. When Jared called she told him she was feeling ill and didn’t want to talk. She knew precisely how he felt when she put down the receiver.

“There’s nothing I can do about it,” she told the radiator.

But on the third day, April became curious. She hadn’t seen Dean in the hall or parking lot. She decided to leave the apartment and go for a walk. On her way out she saw the super lingering in the foyer, his peachy nub of an arm exposed.

“Excuse me,” April said. “Have you seen the man who lives in fourteen today? ”

The super pulled a cigarette from its perch above his ear and stuck the end into his mouth.

“Fourteen? ” he said. “He moved out yesterday.”

April nodded, unable to disguise her disappointment.

“Yeah,” the super said. “Men are pigs. I know. Move on.”

He laughed like a toothless street-corner drunk.

Two nights later, April concluded she would never see Dean again. She wondered if something had happened with Lydia, or if something had changed in Dean. Regardless of what it was, she had lost him; postering the neighbourhood would be futile, if not pathetic. Had he wanted to speak to her he would have done so already. Still, she felt cheated out of a goodbye.

She resumed her calls with Jared under the pretense that she was feeling better.

“Must have been a bug,” was all Jared said.

They still talked about nothing. It was as difficult to say, “No, I really do want to know everything that happened to you today,” as it was to respond to the request.

April got the cable hooked up and began watching the evening news regularly. Always there were stories of abduction, assault, murder. Often the victims were children; sometimes they were teenage girls, sometimes women. One night, while on the phone with Jared, April nearly broke down. She asked him to hold, her voice verging on a gurgle: the onset of the ugly cry. The bodies were discovered in remote places, in cellars, and on deserted beaches. This time, a ravine. The photos, usually blurry or snowy, showed women not unlike April in age and appearance—tonight was no exception.

“Sorry,” she said to Jared, switching the TV off like a frightened child. “What were you saying? ”

Her chest tightened. She had the feeling that if she stopped talking to him the peppermint walls of the apartment might close in, asphyxiating her.

In the wake of recent events, April prepared to fill another void: her apartment. It was a task she’d been putting off since the arrival of Marble. Now there were no longer any distractions. She picked up a framed picture from a yet unpacked box: her and Jared at the lake. She studied her boyfriend’s face and considered the possibility that everyone, in some way, was repulsed by their partner. She wondered if she still missed him.

“I don’t suppose I do,” she said to herself. She set the picture on the coffee table, as if in anticipation.