There are books you read in childhood and adolescence that stick with you forever—books that you read and reread until they become dog-eared and smeared with traces of snacks long since digested. You can quote from them twenty years later as if you had read them last week. It is a markedly rarer occurrence when a book resonates that strongly in adulthood. Sometimes, as age and experience creep up, it seems as though everything from youth was more vibrant, more important—just more than it was.

But sometimes, the haze of adulthood is punctured. Black Coffee Night, the first short story collection from Emily Schultz, can burst the most jaded of bubbles. Throughout eleven stories, Schultz inspects and dissects love, friendship, mortality, and the importance of a good shade of lipstick, among other things. Most of the book’s characters are in their early to mid-twenties and have yet to find the life they once imagined they’d lead. One character watches friends take a magazine quiz, smug with the knowledge that “B” is always the smartest, most normal answer; another knows her mother won’t live much longer but is unwilling—or unable—to stop playing the part of the needy daughter.

The beauty of Black Coffee Night is that Schultz doesn’t rely on irony or cynicism to bring life to these situations. The characters have depth, the plot lines are real, and Schultz gives these urban (not-so) hipsters a warmth often missing from other works of twentysomething angst. Her no-bullshit eye cuts through our culture until people and places stand exposed. In “The Amateurs,” a character sees the city as nothing more than plywood and girders. The first line sets the tone: “The city was nothing but scaffolding that I could see straight through.” It’s not a pretty image, but one anyone who lives in an urban centre will understand. As construction season steps up (though really, with the seemingly endless influx of condos in Toronto and just about every other North American city, does it ever go away?), it’s not difficult to see the world as a series of skeletal structures.

“Accessories,” while in many ways the lightest story of the bunch, lets a fashionable Sex and the City–style woman hang by her own rope as she shows what it means to be self-absorbed. Where Carrie, the story’s protagonist, would, in a similar tale, be a sassy, fun-loving, hair-tossing girl, here she seems pathetically jaded. “We used to do all that stuff together, all these fundraisers and protests, it was so exciting,” the character says of her best friend, Lydia. “It was like a big party except you were there with like a purpose. I felt so united with all these really interesting people. But I don’t know, after a while it just seemed so pointless. They were always looking down on me ’cause the food I brought to the potlucks wasn’t organic….Yeah, me and Lydia were really close though. She was like my sister. When she was in my life, I just knew that I would always be okay. I still call her sometimes, but I feel like she always has something else she has to do….She’s really…Yeah, she’s just…so sad.”

Hal Niedzviecki, the founder of Broken Pencil magazine, who, after seven years at the helm, recently handed his editorial reins over to Schultz, is enthusiastic about her collection. “I’m particularly interested in the stories that delve into the lives of the not-yet-adult, post-university set. A lot has been written about high school and university age, but not much about what is developing as a kind of perpetual adolescent twilight as twenty-five-year-olds struggle to hold on to vibrancy and meaning while dealing with the urge to acquire and achieve.”

Niedzviecki, also an author of young-adult-lost books, such as Ditch and Smell It, has a point. Although “The Value of X,” arguably Black Coffee Night’s strongest work, is the story of a pair of misfit high-school students, it’s stories like “The Physical Act of Leaving” and “Measurement Listings in the Catalogue of Memory” that anchor the collection. Both have at their centre a character named Leigh. In the former, Leigh celebrates her birthday by getting high and jumping in a river. In the latter, she feigns normalcy in the days before her mother’s death.

“I was worried about that one,” Schultz says. “Both my parents are alive, but I have a friend who went through something similar to what happens in the story. I was worried that she would think I was taking her story or that she would be angry about me not writing about what I know, but I think she liked the piece.”

While Schultz may not have dealt with that situation directly, she handles the story without succumbing to emotional manipulation. It is a brutally sad work, but more so because it’s so real (Leigh berates herself for cringing when her parents share a moment of tenderness at the dining room table) than because of heavy-handed melodrama.

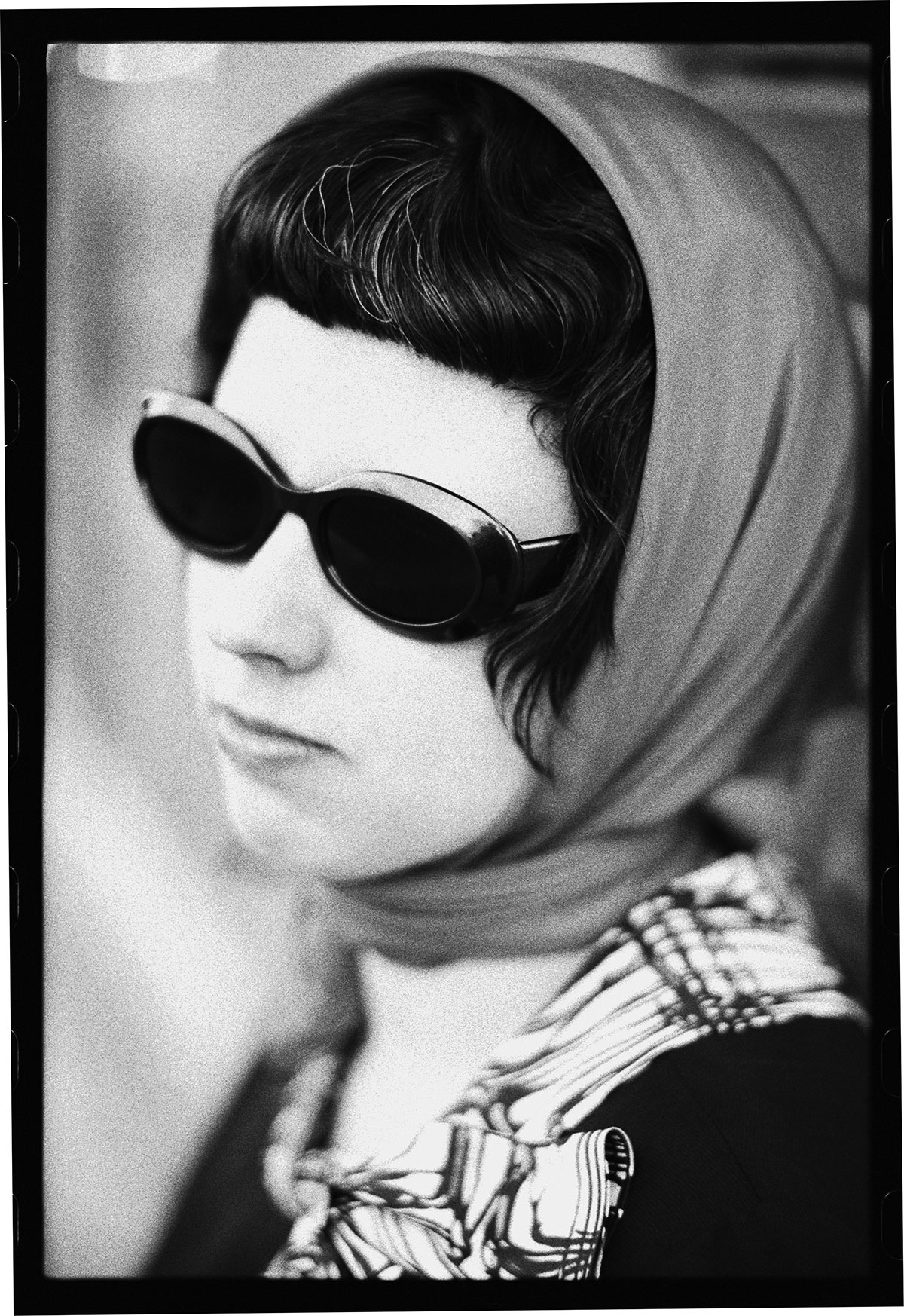

It’s not that Schultz spends her time morbidly deconstructing the world. Though she speaks thoughtfully and with a sense of seriousness, there is also an element of fun about her, a glint in her eye that makes her admission that she sometimes gets carried away when she drinks come as no surprise. At twenty-nine, she appears utterly content with her home in Toronto’s Parkdale neighbourhood, her marriage, and her predominantly nocturnal existence. Perhaps the fact that much of her life is in place makes Schultz so adept at exposing the tiny and not always pleasant details of North American behaviour.

Born to American parents (U.S.-Canadian relations figure in a number of her stories), Schultz grew up in Wallaceburg, a small town in southwestern Ontario. She attended the nearby University of Windsor, where she studied English and creative writing and began to give her first readings, followed by a year in the publishing program at Centennial College in Toronto. Schultz worked a variety of jobs following graduation, including night-shift proofreader of Harlequin romance novels, and production assistant for a pharmaceutical advertising company (“I was terrible at it!” she says. “You could call my old boss, and she’d tell you that, too.”), all the while catching up on her reading. “When I graduated [from Centennial] I went to Virginia for a year, and that year was when I really started reading because I had a lot more time to myself. I was ready. [Black Coffee Night] starts with an Anaïs Nin quote. I’ve read quite a bit of her work, and I think that she’s been really underrated. I kinda started everything late. I should’ve been reading, but I wasn’t.”

In 2002, Schultz made the decision to give up full-time employment and make writing her regular gig. With the help of two government grants and the support of her husband, Brian Joseph Davis, she did just that. Along the way, she has continued to work as a freelance writer and editor upon occasion, including a stint as a travel writer for Naked News. The result of her decision was the publication of Black Coffee Night, which was published this past fall by Insomniac Press.

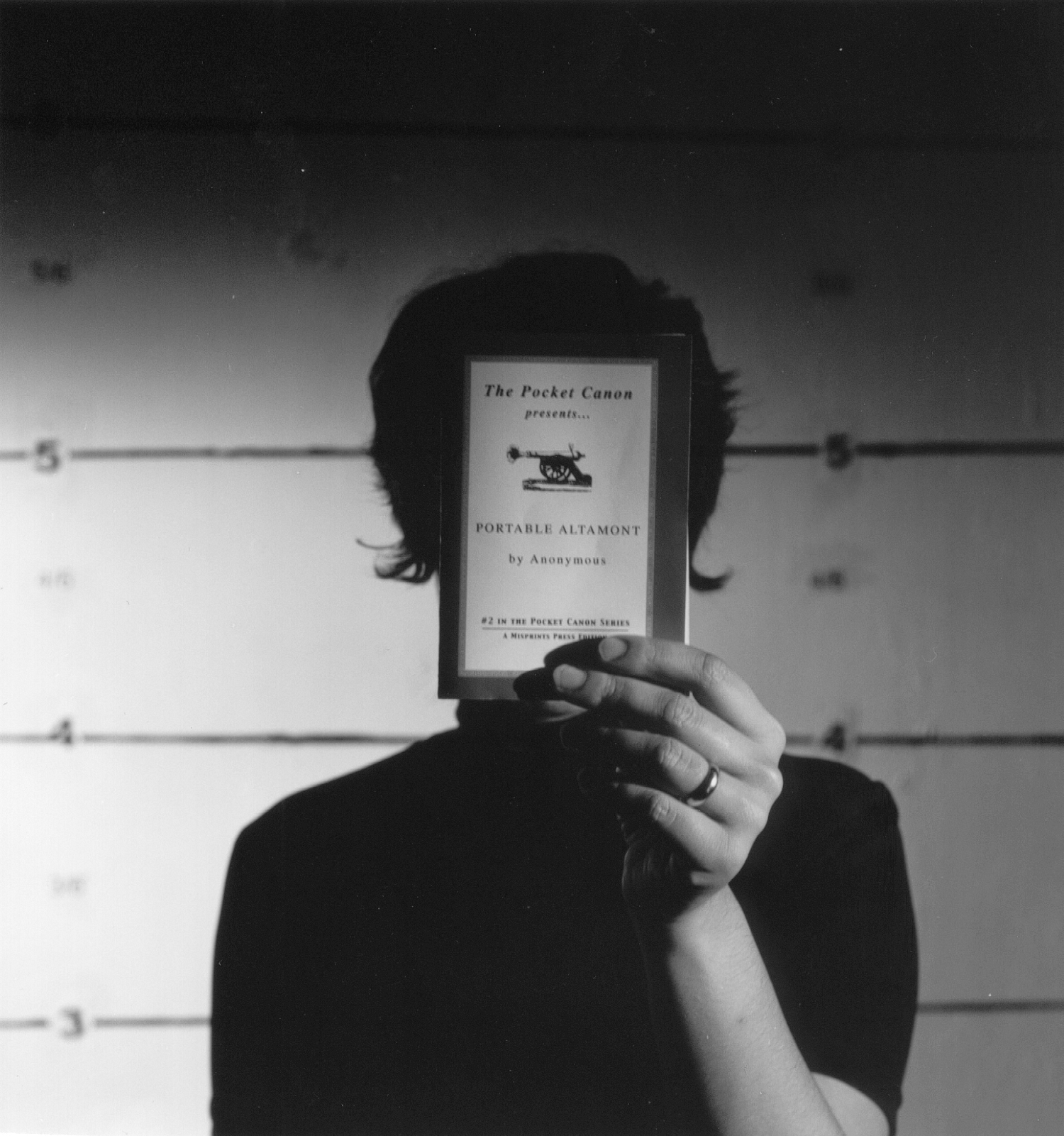

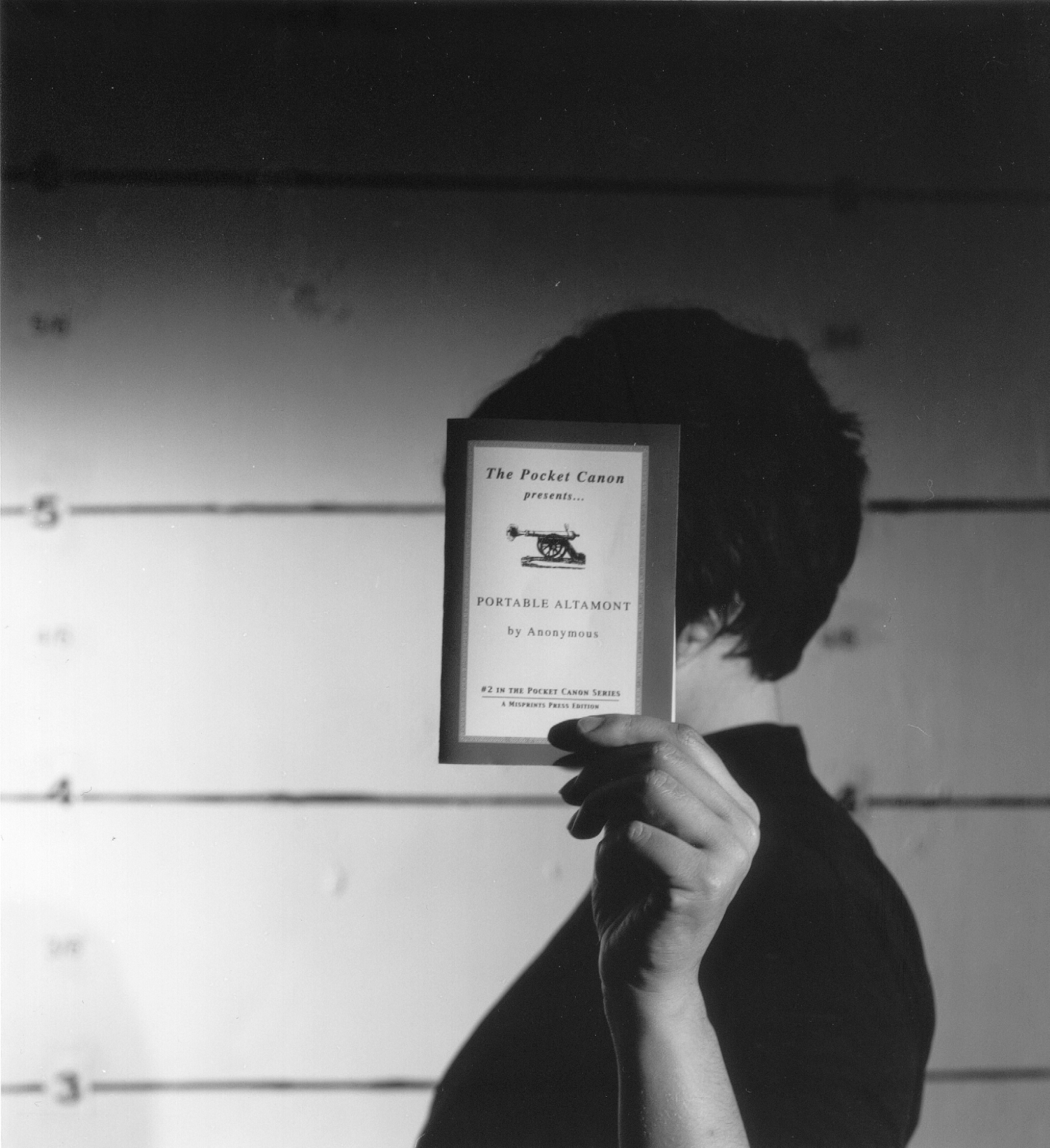

Amidst the fairly straight prose with which most of Black Coffee Night is written is “Watering the Dark,” a numbered, experimental story that Schultz admits works best as a sound piece, and the one that gets a more positive response when read aloud than it did by reviewers of the book. But while the story may seem anomalous to this collection, Schultz is certainly no stranger to literary experimentation. Her latest ongoing venture is the Pocket Canon, a series of small chapbook-zines, curated by Schultz and co-published with Davis. Inspired by nothing more than “the tradition of anonymous publishing,” and the desire to do something fun, Pocket Canons never reveal their authors’ true name. Writers are encouraged to step outside of their regular style and create something new, fun, and unusual.

“I can’t say for sure what makes a piece of writing suitable for Pocket Canon,” Schultz says. “I can just tell straightaway if it is or not. There has to be something about it, but I couldn’t make an outline of what it should or shouldn’t be.”

According to Schultz’s web site, Pocket Canons are for “the libertine, that lover of free expression, gilded editions and independent means. We love small books, but not small ideas. Hence, the pocketbook format is packed with something explosive. Burn us at the stake, ban us from Kinko’s if you must; The Pocket Canon series is by and for authors who know their true identities.”

Maybe it’s the confidence that comes from knowing one’s “true identity” that is the X-factor in an author being chosen for the Pocket Canon series. Or maybe it’s the brashness that comes with knowing that one’s name will not be revealed anywhere on or near the publication. Anaïs, the first Pocket Canon (published in August, 2002), was, unsurprisingly, a parody of the nineteen-forties erotic works of Anaïs Nin and Henry Miller. An amusing little work (of the five Pocket Canons published to date, it is the heftiest, at forty-three pages), what makes Anaïs shine is the quality of the writing. Instead of being a ham-fisted laugh riot, it slips effortlessly into the language and style of its source material. It’s not so much of a goof as a loving tribute, paid without fear of being called out for copping someone else’s style. That Pocket Canons are presented as lovingly detailed little books—with a print quality slightly higher than that of a zine but less than that of a professional chapbook—is just gravy.

Schultz’s search for suitable Pocket Canon fodder is endless, but by no means her only project. In another recent incarnation, Schultz is the new editor of Broken Pencil, Canada’s guide to zine and do-it-yourself culture. Founded in 1995 by the ubiquitous literary presence Hal Niedzviecki, Broken Pencil was originally considered by some to be a second-rate version of its U.S. predecessor, the legendary Factsheet 5. Nearly eight years later, Broken Pencil has taken on a life of its own and has outlasted the now-defunct Factsheet 5, as well as many of its imitators. It has grown well beyond being a simple zine review roundup and become Canada’s indie-culture bible. While it still reviews and excerpts zines, as well as comics, music, and books, it also contains a variety of articles by, for, and about the people who participate in all areas of non-corporate culture, from D.I.Y. poster pirates to backyard wrestlers. As much as it reflects ideas found throughout the indie world, it has also been inextricably linked with Niedzviecki; his humour and outlook grounded the magazine’s content and style. Schultz accepted a huge challenge when she became editor this past November, not only in the sheer amount of work it takes to edit a magazine, but also in injecting her personality into its pages. “It’s a lot of work,” says Schultz, a self-described occasional reader of Broken Pencil. “I haven’t worked in magazines before, so I’m still trying to learn the ropes, but it’s awfully exciting.”

For his part, Niedzviecki feels that, after more than seven years, his time had come to move on, and he is excited to see what Schultz has in store for the magazine that made him a low-income-household name. “I think that after eight years, I was feeling like the magazine could really benefit from a new perspective,” he says.

“I wanted to focus just on writing books and that was starting to show in the pages of Broken Pencil. When your enthusiasm starts to flag, it’s time to find someone else. I’m still working behind the scenes as an advisor and contributor and general ideas guy…and just generally overseeing the mag as head of the B.P. board of directors.”

Though Niedzviecki will remain a key member of the Broken Pencil team, it is Schultz’s name that now tops the masthead. While some may be skeptical about her being in charge of the publication, given her relative newness to the self-publishing world, Schultz has shown an excellent understanding of the genre so far with the Pocket Canon. The quality of writing in the series is far above the average first zine (there’s a lot to be said about waiting until you have something to say before you start talking—or publishing) and the format is beautiful. Even the typesetting recalls dime-store novels, the sort that are coveted by book geeks and pop-culture junkies alike. At a recent launch for Kiss Machine, a Toronto-based zine, Schultz arrived with lovingly rendered poems printed as invitations, complete with envelopes.

“Emily has a clear sense of style,” Niedzviecki says, “a strong vision editorially, and good skills as someone who can keep a project moving forward. She also has connections in the community. She isn’t just parachuting into a job. She understands the B.P. ethos of championing do-it-yourself creativity. All in all, [she’s] a great candidate and exactly what we were looking for.”

While Schultz may not have spent her young adulthood cutting and pasting, she has the requisite traditional organization and editorial skills, which are of an equal, if not higher, value for a project such as Broken Pencil. Heading up the magazine requires not only an editor to oversee day-to-day operations (the magazine currently has a paid circulation of about two thousand), but also a de facto publisher to keep finances in line (and grants pouring in) and an events organizer to ensure its annual Canzine festival continues to run smoothly. Schultz is also putting faith in her section editors, who include Emily Pohl-Weary, a writer and editor of Kiss Machine, and Renaissance man Terence Dick, to ensure the magazine’s continued success.

“I don’t really want to change it very much,” Schultz admits. “It’s not my magazine, and Hal’s definitely developed a readership for it, so mostly I want to keep it the same. Any ideas that I want to put into place were probably in place in my first issue, although I’m sure I’m gonna learn based on reader response….I’d also like to see the magazine have a little more structure than it’s had. I think it’s a little hard to locate yourself in it sometimes, especially since it has so many components. Basically, I figure it will take about a year before I get a hold on the magazine, figure out the demographic, and learn what I need. I definitely want to try to bring the production quality up, but only in the sense that we need to correct the proofs and make sure we’re not getting any errors.”

While to many, independent publishing—especially zine publishing—seems like ephemeral if not inconsequential work, Niedzviecki and Schultz are steadfast in their belief of the importance of Broken Pencil and the self-produced art that it champions.

“I think indie culture and D.I.Y. become more and more important as technology makes more cultural production possible, but distribution and corporate systems shrink our cultural options and our ability to communicate to each other,” Niedzviecki says. “So B.P. will continue to be there to bridge the gap between the explosion of creators and the inability of those creators to find an audience for their work because cultural channels are controlled by corporate systems.”

Although the Pocket Canon series is her first foray into the zine world, Schultz understands the itch to publish all too well. She’s also no stranger to the obstacles faced by a person with big ideas. “A couple of years ago I wanted to start a real magazine,” Schultz says, “but I was right out of the Centennial publishing program, and I was just really naive. There’s only so much work one can do. But I think you have to sort of be naive. I mean, I’m sure that when Hal started Broken Pencil he didn’t know how much work it would be, either. But I wasn’t able to sustain the energy.

“It was going to be called SheBANG, and it was going to be a girlie magazine, in all senses. It was gonna be a pin-up magazine, but it was also going to be a feminist chickie space. It could’ve been a fantastic project and I think it still could, but I don’t have the energy and I don’t have the resources, either. It’s not like I have start-up funds, especially if anybody, even one person, is gonna get paid….We went to Canzine a few years back [to promote the project]. We were a bit ahead of ourselves. We probably should have had a magazine ready before we started promoting it.”

It’s a little ironic that Schultz once attempted to generate hype prior to finishing a project. These days, the work seems more important to her than the buzz surrounding it. At times, she seems hesitant to discuss her work and shy when complimented on it. Her lack of arrogance is charming, however, which surely brings more people to her side. Schultz seems to enjoy a sense of community, whether it’s among old university friends, fellow writers, or just people from her neighbourhood. Even the waitress in her local restaurant knows her by name. When confronted with the fact that the anonymous publisher of the Pocket Canon is growing less anonymous by the day, colour rises in Schultz’s cheeks, just as it does when asked what she likes to do beyond work and drinking with friends.

“I flirt,” she says, looking surprised that she made such an admission.

No doubt, people flirt back.