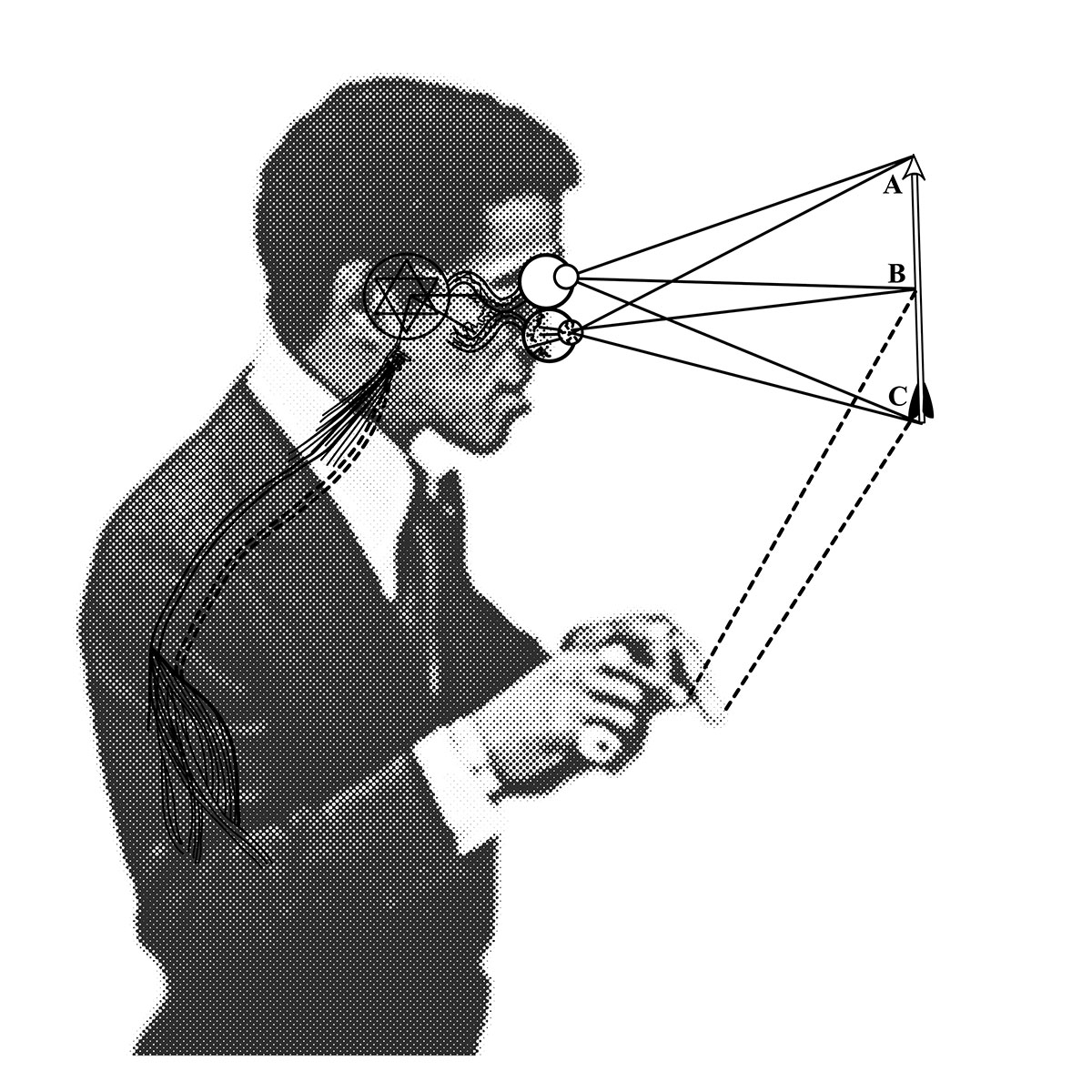

“Candyman philosophica (1954),” by Rick Crilly.

Taddle Creek sent a grotesque, goo-filled candy eyeball to a select group of authors and artists. “Stare at the eyeball,” Taddle Creek said. “Suck the eyeball,”Taddle Creek said. “Eat the eyeball,” Taddle Creek said. “Write about the eyeball,” Taddle Creek said. “Draw about the eyeball,” Taddle Creek said. The writers and artists obliged. (Except for Elvira, Mistress of the Dark. She sent Taddle Creek a merchandise order form.) The stories, poems, and drawing that resulted follow.

Portrait of an Eye

Anna enters a sentence of Kathy Acker’s.

I’m fifteen years old; I hate everyone. I don’t hate everyone (that’s stupid).

Anna was afraid of Kathy Acker. Anna imagined Acker lying naked next to a naked lover, whoever that may be, there were many, the tips of their noses and their nipples touching. Acker always seemed fierce, mutable muscles blue with tattoos, roiling beneath Japanese garments. Anna had only one small tattoo, an insipid yin-yang symbol at the base of her spine. Her lovers stared at it as they fucked her from behind—an eye of sorts, mocking in its insistence on a universal order.

I fuck and find out my mother’s been lying.

Anna was writing a biography of Acker, trying to. She had already spoken to many of Acker’s friends, writers mostly, travelling to Paris to talk with Dennis Cooper, to San Francisco, where she stayed with Dodie Bellamy and Kevin Killian. In New York, after their lengthy interview, Lynne Tillman wept slightly, not wanting Anna—or Acker—to leave. Unravelling Acker’s self-mythology was difficult enough, but more so was confronting the confounding, multivalent versions of “Kathy” other people still carried around with them like juju. Her ghost haunted everything except perhaps literature. Her example was forbidding, forgotten.

I know my mother lies about everything.

A troubled youth, Anna’s niece was fifteen, trying on trouble. Over some minor dispute—her mother refused to let her see her boyfriend, etc.—she threw a tantrum. She threw a mirror at her mother, Anna’s sister, and it shattered, glass cutting her mother’s fat flesh. Anna’s niece fled her suburban house, into the forest. She lay on the floor of the forest as it snowed, wet flakes ruining the makeup she insisted wasn’t goth. Police were called; their boots opening up fresh holes in the snow. She said to them, “There’ve been times I’ve wanted your death, Mom. At least, didn’t much care.”

Everything is incredibly beautiful.

Anna’s niece had never heard of Kathy Acker, read only Gossip Girl, but Anna would dedicate the biography to her. She wanted the girl to become something she wasn’t. To be something Anna wasn’t, or her sister, as fat as Gertrude Stein, wasn’t. But maybe Acker could save her niece’s life, as Acker had saved hers. This girl could still be a pirate, just as surely as pirates somewhere still roamed the seas.

—JASON Mccbride

It was an Accident

It was an accident. Nobody would ever find out. Nobody ever did.

“I got a knife.”

“Why’d you bring a knife? ”

“Always be prepared.”

“But that’s your dad’s hunting knife.”

“So? ”

All in our store-bought costumes. A cowboy. Freddy Krueger. The littlest one a penguin that won’t stop crying.

The lights in the houses through the branches. The Dillons’ annual theme-park production. Screams and thunder and a creaking door carried on the wind from a haunted-house sound-effects record. A floodlit man hanging from the front yard maple. Garbage bags stuffed with rags.

“I’ll go first. First gets to choose.”

“Who says? ”

“Here. You want it? ”

“Bet you can’t.”

“Watch.”

We take it apart. Take a part.

After, we stack our hands in a slippery pile. Blood brothers, though some of us are actual brothers. Swear to die if we ever told. All still alive, as far as I know. That night, I pull out the box from under my bed. Look at it. Looks at me.

I would never try it in the daylight. But now, in the dark, I stick out my tongue.

—ANDREW PYPER

First Prank

“Put it in a baby stroller.”

“Wrap it up as a present.”

“Put it in Shitzer’s lunch bag.”

Em paused and looked down at the fetal pig on their table. Gelid. Arrested.

It stoically received Travis’s pencil in its tapioca eye.

“We could cook it in the staff room.”

Travis raised an approving eyebrow at her. The teeth in his grin sloped and snaggled. She knew his jeans were too tight, his bitten fingernails rimmed with grime. His house, she imagined, had a tang of Chef Boyardee and nicotine, different radios playing in every room.

In Grade 5, Em used to take Travis’s gloves from his pocket in the cloakroom and smell them. Grass and hot dogs. He’d set the A.V. room on fire in middle school and everyone got a half-day. She hadn’t seen him again—tall and vacant—until Grade 11 biology. People said he was dating a woman old enough to have bags under her eyes. Em saw him one day at a bus stop holding a purse with a raccoon tail clipped to the strap, and he went blotchy red when he noticed her staring. She’d never made anyone blush before.

After that, they talked at school.

Travis reached into Em’s backpack and pulled out her lunch bag. Dumped out her sandwich and shook the crumbs from the container. He winked one of his skim-milk eyes and slid out of his seat. At the back of the classroom, he scooped a pig from the plastic tub into Em’s sandwich box and was back beside her before Mr. Spitzer noticed he’d left his seat. Travis leaned close, passed the pig under the table. As he spoke into her ear, his vinegar smell coursed overtop of the formaldehyde.

“Shitzer would never suspect you. Just ask to go to the bathroom. The staff kitchen on the third floor has a microwave.”

The tiny pig was pale as a rose petal, plump as a marshmallow. Em reapplied her lip gloss while Mr. Spitzer said, “…ventricle, aorta, electrical impulse.” She raised her hand. Her heart spat static like a radio thrown down the stairs.

—SUSAN KERNOHAN

Telltale

I can feel it watching me.

Mother is watching me too, when she thinks I won’t notice.

I won’t notice either of them. I won’t. I’ll just sit here quietly and read my book and no one will know what I did today.

It’s really not my fault. Sometimes things just…happen. There I was and there it was and it just…happened. Like things do.

I’m not supposed to do that. I know that. I promised Mother. I promised the shrinks she made me see. I promised myself.

But things just happen.

And it wasn’t entirely my fault. It had something to do with it. It bears some responsibility. I didn’t ask it to be there, to be so easy to take. To be so easy. The least they could have done was take better care of it.

I stare at my book but the words are just black marks on the page. My mind is full of it.

It took just a moment, just a quick glance around, just a moment’s reach. No one saw me. No one knows.

But I can still feel it watching me.

I hid it in a secret place, one that Mother doesn’t know about. But not too well-hidden. I want to be able to get to it, after all. No point in hiding it so well I can’t get it back in good condition. I left one too long once. It wasn’t very nice when I finally managed to find it again.

I sit in my chair, listening to the clock tick, staring at the black marks on the white page.

I can feel Mother watching me.

I can feel it watching me.

Mother looks up suddenly, frowning. Looks up at the ceiling, as if she can see it through all the wood and plaster. As if it can see her.

I cannot stand it anymore. It will drive me mad with its staring, its relentless, reproachful gaze.

There’s only one way to make it stop.

I rush upstairs, aware that Mother is behind me, aware that I’m betraying this hiding place too, but it doesn’t matter.

I find it and it breaks between my teeth and the sweet, forbidden taste of it fills my mouth.

I’ll be punished, of course. I’ll promise never to do it again.

But I will. I can’t help it.

—NANCY BAKER AND ERISA NIRU

The Complete Works of Derek McCormack

“True,” I replied, “the armadillo.”

As I said these words I busied myself among the pile of bones in this cellar, which I have spoken of before. Throwing them aside, I soon uncovered a large quantity of slim novels by J. G. Ballard, Italo Calvino, Thomas Mann, Ian McEwan, Philip Roth, Marguerite Duras, and others. With these materials and with the aid of my trowel, I began vigorously to wall up the entrance of the niche where drunken Jeffrey Archer lay enchained.

I had scarcely laid the first tier of books when I discovered that the intoxication of Archer had in a great measure worn off. I laid the second tier, and the third, and the fourth; and then I heard the furious vibrations of the chain. The noise lasted for several minutes, during which I ceased my labours and sat down upon the bones. When at last the clanking subsided, I resumed the trowel, and finished without interruption the fifth, the sixth, and the seventh tier. The wall of books was now nearly upon a level with my breast. I again paused, and holding the flambeau over the books, threw a few feeble rays upon the figure within.

A succession of loud and shrill screams, bursting suddenly from the throat of the chained form, seemed to thrust me violently back.

It was now midnight, and my task was drawing to a close. I had completed the tenth, the sixteenth, and the twentieth tier. I had finished a portion of the last; there remained but a single book to be fitted and plastered in—The Complete Works of Derek McCormack.

I struggled not with its weight.

I placed it partially in its destined position, near Archer’s eyes. But now there came from out his niche a low laugh that erected the hairs upon my head. It was succeeded by a sad voice, which I had difficulty in recognizing as that of the noble best-selling author. The voice said:

“Ha ha ha. He he he. A very good joke, indeed. An excellent jest. We will have many a rich laugh about it at the palazzo. He he he—over our pet—he he he.”

“The armadillo!” I said.

—BRIAN JOSEPH DAVIS

Tillian and the Hairy Eyeball

So I’ve got this route I take every Halloween to maximize my haul, and it ends at Mrs. Tillian’s. Even if I’m out with friends, I hit her place alone. She sits there, waiting for me to show up, because she just loves to flash me the hairy eyeball. It’s the highlight of her entire year.

Somehow she always knows it’s me, no matter if I’m dressed as a skeleton, a businessman, or Janet from The Rocky Horror Picture Show. Old Till’s face starts a-twitching and her eyes narrow to tiny little snake slits. It’s hilarious, in an awful way.

She hates me so much because I’m a total slut. When I was eleven, she caught me doing something unmentionable to Rocky Mason behind her shed. Rocky lives two blocks over. He has curly red hair around his thing and the whole time I was doing it, I kept imagining it was carrot-flavoured dental floss. What no one knows is that Rocky threatened to strangle her stupid cat if I didn’t. I was saving a poor innocent little animal! God, she should thank me.

O.K., there’s another thing that happened. When I was thirteen, she chased me out of the Colombian church on the corner for playing spin the bottle with Bobby Santos and some other kids in the basement. Bobby Santos—who thankfully doesn’t have red hair—and I were pretty much in love and kept making the bottle land on each other. When we finally got sent to the closet for seven minutes in heaven, we decided not to come out again.

Next thing I knew, there was crazy old Tillian, yanking open the closet door with her wooden broom swinging righteously. She snapped me right in the thigh and it hurt like hell. She slammed Bobby in the stomach and he puked on the church floor. He can barely even look at me now, probably because he’s reminded of her.

She’s one of those old ladies who wears black all the time, except she’s not that old. Her husband croaked while he was shovelling the walk five years ago. I was too young to really care, but my mom says he was a hard-living fifty. Whatever that means. Secretly, I bet Till’s evil eye bounced off its intended target and landed on him one too many times.

She thinks that one day God will notice all her hatred and smite me or something. Like He’ll decide to make me choke on some hot guy’s tongue or catch a killer S.T.D. Then she’ll be the supreme winner, because I’ll finally stop coming to her door to taunt her. Because I’ll be dead.

I only go to her place because she’s so nuts. I mean, I’m fifteen, which is way too old for trick-or-treating. Plus I’ve got a job, and can afford as much crapola candy as I want. And she gives out those disgusting brown taffies that rip out your fillings and sit brick-like in your gut for at least a week. The only real reason to go anywhere near her is to show her I’m not afraid, that I remain victorious.

—EMILY POHL-WEARY

Which is Scarier?

Options:

- You and your child go on a canoe trip in Algonquin park. On the second morning, you awake early to fog. After packing up, you head out onto the lake. Paddling along, you see something ahead on the water through the mist. You realize it is a rowboat, although nobody seems to be in it. You paddle up. You are in the bow and your child is in the stern. You lean forward to get a good look while your child steadies the boat. You see that the boat is full of blood and there are two human eyes floating in the blood, and a little bit of blood slops up over the sides of the boat as the boat rocks in the waves, while the eyes stare at you, bobbing side by side.

- A skeleton riding a horse.

Answer: The boat of blood. Don’t be stupid.

—PASHA MALLA

In

injuries result from objects striking or abrading the eye, such as metal slivers, wood chips, dust, cement chips, nails, staples, or chemicals

injuries from razor blades, scissors, robots, tweezers, pebbles, box cutters, ice picks, keys, meat cleavers, sabres, swords, teeth, arrows, ski poles, spears, drill bits, tent poles, fish hooks, throwing stars, turpentine, liquid bleach, skate blade, cheese in pressurized containers, yogurt, toothpaste, Christmas bulbs, push-pins, syringes, slivers, cement, chemicals

ladybugs, bee stingers, mosquitoes, hummingbirds, feather stuck in an eye, dragonfly across an eye, flayed eye, knifed, a fork, fuck my eye, my eye in a needle I need I eye Captain Hook fuck metal hooks, chips, dust, chips, snails, staples, chips, tails, teeth of a whisker of a tiger, survivor, chemist

beauty is performed by external incisions or pencils, pens, penises, or pensions, fucked in the eye, fucked by the government, headache like migraine auras like metal slivers, wood chips, dust, cement chips, nail, staples, or chemicals, or chemicals

—ANGELA RAWLINGS

Afraid

Cold feet cold feetmiscue

Foul, offensively foul, is everyman

bursting in at your door

The treats and tricks of language unconclude you You knew that

Colon’s for Halloween, no? And comedy? And smug human

rights? How about the cruel huckster? Turning your pockets

inside out? Or maybe that’s humanist

Offensively free is the unco everyman

undefined, invading your pious trade

Fob off a gumball eyeball for an eye, fall afoul of

the advance man slouching in grim

with lacquered frown

Gain is no word for it

Even the candy goes

(candy for the baby, your pie of live blackbirds)

—BETH FOLLETT