The staff of Ten Foot Henry were busy serving a nearly full house during a recent Sunday evening visit. Patrons of the popular restaurant, which opened in 2016, in the century-old Eagle Block, in Calgary’s Victoria Park area, enjoyed plates of tomatoes and feta on toast, spaghetti pomodoro, and green beans with honey. Few paid much attention to the venue’s eponymous mascot: a ten-foot-high plywood effigy of a Depression-era comic strip character, bolted to the wall just off the dining room. “We don’t get asked what the story behind him is as often as I thought we might,” said Aja Lapointe, who owns the restaurant with her husband, Stephen Smee. “I’d say about eighty-five per cent of our guests don’t know about or care about the connection.”

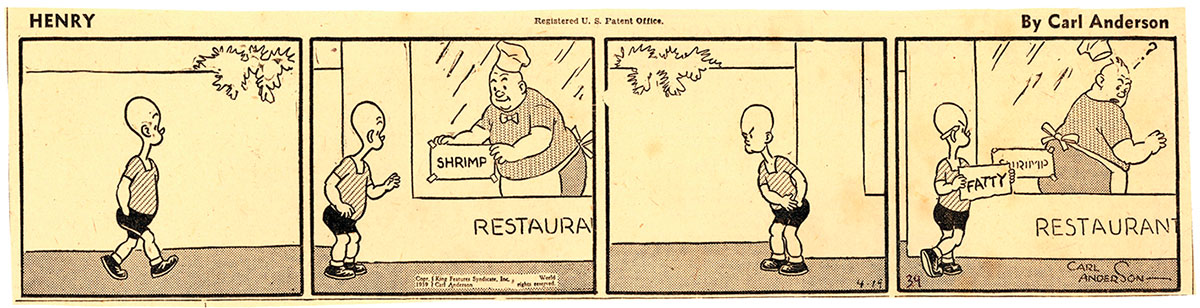

Henry was created in 1932, by Carl Anderson, an illustrator from Madison, Wisconsin, who for many years had more success as a cabinetmaker than he did drawing comics. Anderson’s character is a boy of grade-school age, usually outfitted in a red shirt and short pants. Henry’s clothing, combined with his long face and peanut-shaped bald head, gives him the appearance of an old man dressed up as Charlie Brown for Halloween. Henry lives a fairly idyllic childhood of fishing, afternoon movies, and ice-cream cones. He’s also unusually randy for a child, especially as portrayed by John Liney, Anderson’s former assistant who took over the weekday strip in 1942. The character originally appeared in the Saturday Evening Post before drawing the attention of William Randolph Hearst, who signed Anderson to create a daily Henry strip, which still appears in newspapers today, though new installments stopped being produced in 1995.

In 1981, Blake Brooker, the co-founder of the performance theatre One Yellow Rabbit, commissioned a friend to create Henry’s larger-than-life Prairie counterpart, which he propped up in his yard, overlooking the Macleod Trail expressway. Brooker outfitted Henry with a series of thought bubbles, featuring messages like “Depressing, isn’t it?”—commentary for passing commuters during the peak of the oil boom that was then shaping Calgary’s inner city. Brooker’s choice of characters is ironic, considering, outside of a few instances, Anderson’s character is mute, speaking only in pantomime.

Brooker later loaned Henry out to a Sixth Avenue dance club, which took the name 10 Foot Henry’s as a tribute. (The singer Janet Panic was so inspired by the club—which also hosted acts such as Art Bergmann and 54-40—she named a band after it.) The club closed in 1986, and Henry eventually found his way to another music venue, the Night Gallery, located on the second floor of the Eagle Block, a building with a long history in the arts. It initially was built as home to a chapter of the Fraternal Order of Eagles, a club for those involved in the performing arts. In more recent years, it has housed a series of music venues, most notably the Night Gallery, where Henry lived until the club closed, in 2005, making his home life somewhat unstable as a result.

Lapointe was not immediately sold on the Eagle Block when she and Smee began looking for a space to open their first restaurant. “All I saw was a money pit,” she said. “But my husband tried to make me see its potential, and I’m so glad that he did.” The couple quickly discovered and became enamoured by the story of the Henry cutout. “We were going to be opening a contemporary, casual restaurant, but we wanted to have some kind of back story and utilize the history of the space,” Lapointe said. “Since he lived here for so long, when we were looking at this space, we though he was a colourful bit of Calgary-ana a lot of people didn’t know about.” Lapointe and Smee contacted Brooker, who agreed the restaurant was an appropriate place for Henry’s next adventure. A hallway leading from the bright, contemporary dining room toward the bathrooms was the only area with ceilings high enough to accommodate the figure. The location also allows diners to take pictures without bothering other guests.

“We like that we’re able to perpetuate this now thirty-six-year-old story,” said Lapointe, who drew most of the Henrys that accent the restaurant, with the exception of a large mural near the entrance that was traced from an Anderson original. “It makes people kind of smile and laugh. The cards we give out with our bills are original Carl Anderson Henry comics. Both my husband and I like the idea of taking the pomp and circumstance and pretention out of dining. I think in the past twenty years we started to get pretty pretentious. We love that the name of the restaurant doesn’t speak to what we’re doing within the four walls. We like having a playful menu that doesn’t fit in a box.”

Henry’s future is secure for at least another fifteen years, the length of Lapointe and Smee’s lease. Lapointe calls the restaurant a long-term project, though she will be temporarily stepping aside soon, when the couple welcomes their first child. Will the baby be named Henry?

“Definitely not,” Lapointe said, without hesitation. “We already have a Henry.”