Quarla is bitter-tasting and grisly. Maybe wild beluga tastes better than the ones born in captivity, like free-range chickens and wild salmon. I go back to the barbecue pit and line up for seconds anyway. It’s not about taste or hunger anymore because packages of food started parachuting down from the sky an hour or so after we put Quarla on the spit. But if we abandon her now, everything will be lost. Nobody speaks, and the only sounds are of laboured chewing and swallowing and the odd reflex gagging as everyone tucks into the meat with grim but orderly determination. Actually, eating the beluga seems like the sanest thing we’ve done the past four weeks, maybe in our whole miserable, cruel lives.

We were in total denial of our misery in those early days, so life was pretty great. Everyone was showing up at work but mostly to trade information about the terrorist attacks in Washington and L.A. and to watch CNN on the boardroom’s big-screen TV. The upper managers seemed to loosen up a bit around the water coolers and even conversations about the weather revealed intimate things. By about 2 P.M. most people cleared out for the beach or to drink at sidewalk cafés or take advantage of the amazing store sales. Of course, after the incident at Banana Republic, which was called a riot but was really very orderly, with people in capri pants and pastel tank tops swapping sizes and compliments or advice, retailers started closing and independent kiosks appeared, selling second-hand clothes, massages, henna tattoos, ceramics, haircuts, and excellent homemade food. With the outrageous gas prices, everyone, even the police, took to walking and biking. Some people walked around on stilts, creating a summer festival feel; it was incredible how many people owned stilts.

Everyone got more sleep and more leisure time and realized this was the way they wanted to live. We had all this time to get to know each other, along with some of the tourists staying on at the hotels, taking advantage of the discounts. I made lots of new friends at my apartment because there were never any awkward silences in the elevator and everyone got right to the important stuff. One was this very cute guy named George, who lived on the twenty-eighth floor and worked at the aquarium in Stanley Park. Sometimes we’d go up to the roof and talk about the future, and I could see this guy in my future, which was a relief, finally. It seemed like anything was possible and that the crisis in the U.S. could be a great opportunity to alter the way we lived without making too many hard changes. The tenants started meeting in the party room, downstairs, and began work on solar-powered blueprints and a vegetable and herb garden. By the time Abdul, the building manager, disappeared, the complex was running better than ever.

One Monday, four water trucks in the downtown core were hijacked at gunpoint, so the water-cooler water ran out. The New York Stock Exchange closed down the next day and none of the upper managers or Accounting Department staffers showed up for work that morning. They had all left polite messages on their voice mail that they were on summer vacation, or forwarded their phones to Gertrude, the receptionist. Gertrude forwarded her phone to the conference room where we all hung out watching NBC and CNN broadcasting from their new secure locations. Some of the commuters decided to move into the building and took over the corner offices, while others stayed at home, calling in the occasional news of lootings at Costco and Ikea. That Friday, all the downtown banks I passed on the walk to work were boarded up, with armed guards stationed in front. There were no paycheques anyway. Harold, from the I.T. department, followed me into the women’s washroom and said, “Look, my brother’s got a sailboat at False Creek. We’re heading up the coast tonight. Come with me.”

“You’re so very too late,” I thought, but I told him I had to go to a birthday party tomorrow at the aquarium for the baby beluga whale.

He looked at me like I was nuts and said, “But I’ll take care of you.”

I couldn’t believe it, thinking, “You could have stayed the night that time I told you those things I never thought I’d tell anyone. But no, you couldn’t get away fast enough could you? ” I said, “No. I’m staying here.”

“You’re not going to be safe here,” he said, and when I laughed he said, “Fuck you then,” and marched off with the three new iMac laptops, and all sorts of computer cables round his neck.

Everyone made a point of leaving with something from the office, and people were fighting over the stupidest things in the storage room, like the overhead projectors, as if there’d be an urgent need to put graphs and pie charts up on walls. Rick and Cam, from Marketing, even fought over the smelly old company mascot. Rick was wearing the big fuzzy bear head, and Cam tried to knock it off him, so Rick kicked Cam in the groin and made a run for it. It didn’t make any sense until I saw footage of him later on TV attempting to rob a store in Chinatown. Because he wore the big head, his peripheral vision was obstructed, so he didn’t see the baseball bat coming.

That fight really got everyone riled up, and we basically pillaged the storage room. I got a choice selection of Post-it notes and three giant jars of Coffee-mate.

The air on the streets was thick with a new kind of tension. There was a huge lineup in front of Safeway, and only mothers with screaming babies were being let inside, because the store couldn’t keep up with food rations. I beelined home, thinking, “T.G.I.F.,” and then, “How stupid. It doesn’t matter now.” At the apartment, people were hanging around the pool, swimming and barbecuing. Larry had lucked into three cases of frozen hamburgers. He had a black eye and a bloody lip, but nobody pushed him for more information. Shona told us the border had been closed because thousands of Americans were trying to get into Canada. There’d been more riots the previous night in Seattle and all over the States.

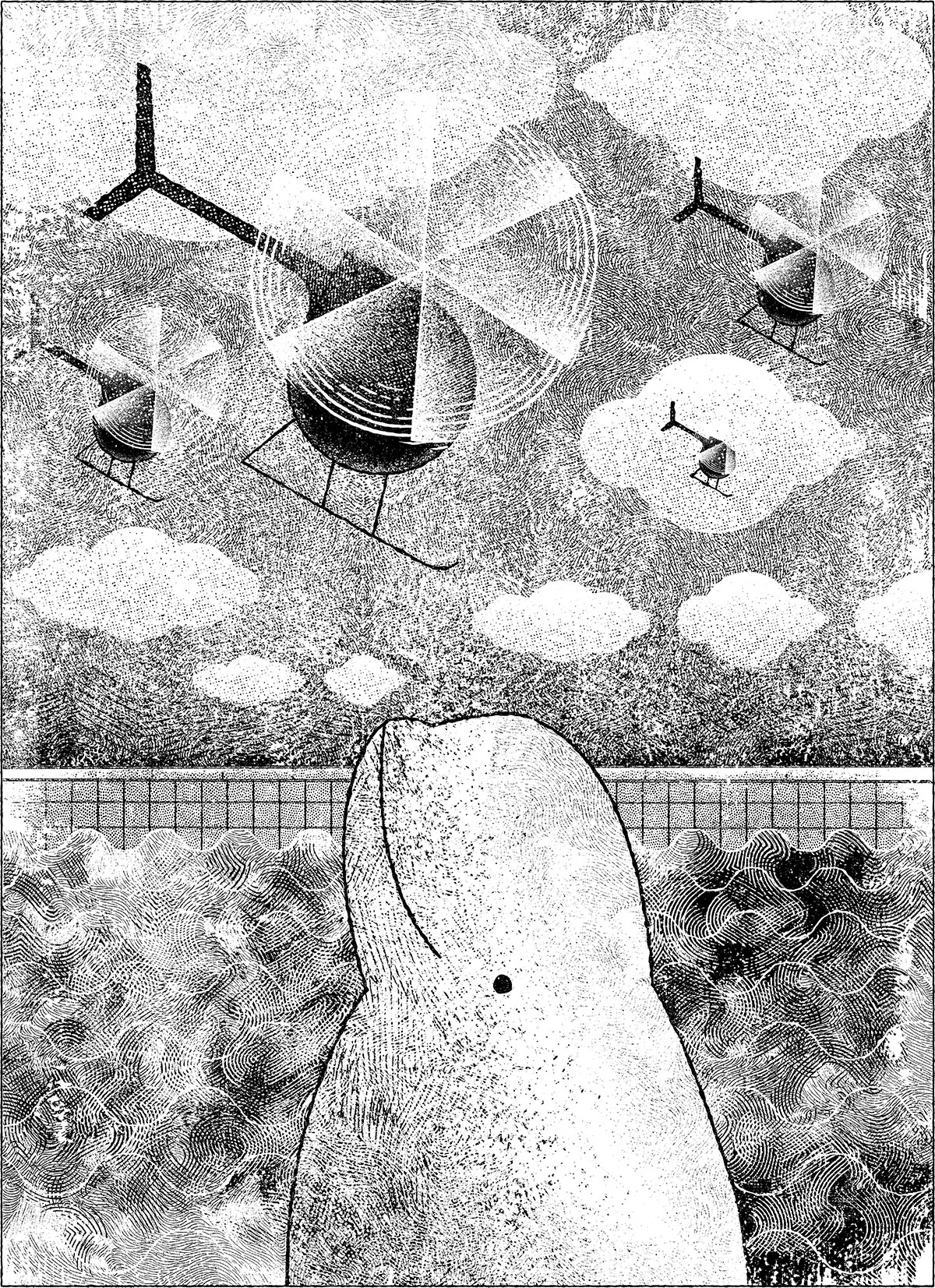

I ate meat for the first time in five years and had a romantic candlelit night with George. There were flecks of green in his brown eyes, and I thought, “Yes, this is the one.” I said, “I love you,” and felt terrified. When he didn’t say anything back, I wanted to just disappear. He said it later while we were having sex, but it was like he was talking right through me to someone else he was angry at for hurting him. At least it was something, though, and in the morning we held hands walking to the beluga birthday party. It was a beautiful blue-sky day, but, with the black helicopters slicing through it all over the place, ominous.

Animal-rights protesters were picketing in front of the aquarium. A couple yelled and spat at the ground in front of us as we went in. But inside it was nice and cool; there were people making balloon animals for the kids, and the belugas, with their big smiley heads, looked so happy and curious.

As the cake was being sliced, the power went out, and some people immediately got kind of hysterical, packing their kids into strollers and rushing for the exits. The generator kicked in and I went with George and some staff people to the admin offices to check out the TV and the Internet. The servers were down but what we saw on TV was unbelievable. CBC showed pockets of Toronto on fire, standoffs between farmers and suburbanites in the Prairies, and, in Vancouver, angry demonstrators burning shapeless effigies in front of banks. Then the footage of Rick in the bear head. I couldn’t help thinking there’d be trouble at the office come Monday, and then, “Stupid, there will be no Monday like that anymore.” I felt kind of euphoric. They interviewed the guy who ran the kayak school down at the beach, who’d been beaten with his own paddles by a group of women posing as sunscreen merchants. The women stole his kayaks and paddled off westward; you could still see them as dark splotches heading north on the Strait of Georgia. The strangest thing about the footage was that there were also people lying in the sun and kids swimming in the bay, just like every Saturday. But there was nothing normal about the footage from the States, where tanks had taken over the streets and Arabs were being hauled away to who knows where.

The vet said we should turn off the TV because we only had about twenty hours on the generator. “That’s it. After that the Arctic habitat will start warming up,” she said. So staff started discussing what to do about the belugas, dolphins, otters, and sea lions. Their food supplies in the two seven-tonne freezers wouldn’t last long; the belugas alone ate more than fifty kilograms of food per day. How were they going to feed over sixty thousand species of fish, birds, reptiles, and mammals?

Outside, the protesters were yelling, “Free the whales!” and “No whales in captivity!” A security guy said they were having trouble holding the protesters back, so the aquarium director ordered a bunch of tranquilizer guns loaded up and guards were stationed around the perimeter of the aquarium. By dusk, ten or so protesters had been shot. A few were shot more than once, after waking up and groggily advancing again, looking like brain-eating zombies. George and a few other guys organized a mission to see what was happening outside and, if necessary, find an evacuation boat. They took a couple of tranquilizer guns and headed for the back entrance. I wanted to go, too, but George said I’d be too much of a burden. He shrugged my hand off his shoulder and didn’t even look back. Anyway, I was stationed at the entrance to the Amazon rainforest to make sure none of the turtles wandered out. It was a tough job because the only thing keeping them in was the temperature and, with the air conditioners turned off in the other areas, the whole place was starting to heat up. But the director was adamant about maintaining normalcy and keeping the facility functioning as usual.

Even the tree sloth moved slower than usual up in the tree.

George didn’t come back that night. I thought about Harold, from I.T., and wondered if I’d made a big mistake and would never find anybody to love. I wanted to at least go to my apartment for a while, but the three people that had left over the past few hours had been held hostage by the most militant protesters, who wanted the whales released immediately. They had even broken a man’s finger, but the aquarium staff wasn’t budging for anything. Someone called the Fisheries Department but, naturally, didn’t get anyone on the phone. Plus, of course, what would all these people do without the belugas? Their whole careers depended on those whales.

I started getting impatient keeping the turtles and tortoises. The tree sloth stared down at me noncommittally, but I felt it must be judging me. We ate shrimp and crab for dinner. It tasted fine at first, but I developed terrible cramps later. On my break, I went to the underground viewing area of the beluga habitat and watched the whales. Mostly they were hovering at the bottom of the pool and not moving much. An animal trainer named Trudy said the whales were stressed out and that their heartbeats on the monitor were too high.

“Maybe we should try to get them to the bay,” I said.

“Then what? ” she snapped back at me. “They wouldn’t know what to do out there in the wild.”

So I didn’t say anything, just sat quietly watching the belugas, and their heartbeats on the monitors, and feeling terribly sorry for them with nowhere to go. I wondered if they could sense the sea water surrounding them, sense that it was so close but impossibly far away.

“You know, belugas have higher I.Q.’s than us,” said Trudy in a quiet, normal voice. She told me about a beluga named Minsky who beat a Russian chess master in less than an hour.

I told her that there used to be sloths that lived on the ground but they didn’t survive. Only the tree sloths survived. I wondered about our chances of survival with our little round human brains. Then, I wondered, “What is our natural habitat? What kind of place would be designed for us in captivity? ” Quarla, the sixteen-year-old who lost her baby two years ago, came swimming up to the glass, smiling calmly, as if to say, “It will be O.K. We’ll all be O.K.”

By morning there were over five hundred people outside protesting. The situation everywhere had deteriorated to the point you’d have thought the protesters would have lost interest in freeing the belugas. But the eruption of chaos and fires in the city had sent more people into the park, and it seemed like they all enjoyed having something to scream about. One guy from George’s team came back in shock and covered in blood. The vet examined him and soon rumours started circulating that he’d been raped either by gangs of rogue downtown security guards or by vigilante small business owners. That’s when it really set in that we were trapped here. Finally some police showed up and got the hostages outside released. Then they pepper-sprayed the protesters for a while and got them backed off enough so they could take turns dining on the last of the crab. They agreed to keep two cops at the aquarium and argued amongst themselves about who’d stay. Eventually, they agreed to take shifts. It was good having some real guns on the premises because our animal tranquilizer supplies were dwindling.

There was nothing I could do about keeping the butterflies in the Amazon rainforest, and every time the main doors were opened, dozens of butterflies would escape and work up the protesters. People from the S.P.C.A., Greenpeace, peta, and the W.W.F. were waving banners and handing out Frisbees and T-shirts that said things like “WANTED: TIGERS IN THE WILD.” Some of us started saying that the protesters were right and we should just free the belugas—what else did we have to do? We could make huge slings and fix them to a flatbed truck if we could find one. But we were afraid to get too vocal because the director had the security guards, trainers, and P.R. people on her side and they’d already turfed a couple of dissenters who’d been used as human shields against the pepper spray.

We ate barbecued snakes and turtles for dinner and the smell must have travelled because by nightfall thousands of people had joined the mob out front. The R.C.M.P. moved in and, to the director’s shock, they started rationing out food and fresh water to the mobs. Some people dropped their banners to tuck into the frog legs and octopus, while others started shouting slogans like “Meat is murder” and “Eat the rich.” So, the R.C.M.P. began letting mothers and childen into the aquarium. A nursery was set up in Clownfish Cove and the children got to learn all about the fish that would eventually be eaten. They also wanted to see beluga and dolphin shows, but the trainers drew the line at that because the Arctic tank was way too warm. The poor belugas were so stressed that their heart rates were constantly elevated, but it was hard to appreciate their distress, what with the huge grins on their faces.

Overnight, Alohaq, the dominant male in the dolphin tank, went berserk. He started ramming into the other dolphins and nipping at them. Even after he’d been shot with a tranquilizer, he continued ramming into everything, finally knocking himself out. He was in such bad shape the vets decided to put him out of his misery. So we had lots of new meat, but when the rations were sent out to the mobs, a dozen or so militant animal-rights protesters went crazy and started attacking people with their picket signs and sets of abandoned stilts. One protester was killed by a rubber bullet.

Inside, things also took a turn for the worse. Nobody was getting along or doing their jobs, and assaults became pretty common after the fresh water supply ran out. I spent most of my time in the trees with the tree sloth. I’d feed him a few bits of whatever meat was on the menu. Tree sloths are vegetarians by nature, but I was determined some species on my watch survive. Since their metabolisms are so slow, they really don’t need to eat much anyway. We could have avoided so many mistakes just by slowing down and climbing trees once in a while.

“I love you,” I whispered to the sloth. It stared back, unblinking, and it wasn’t scary.

“The belugas are plotting against us,” Trudy whispered to me late one night while we watched them from the underground observatory. True, they’d become more vocal since the power went out, but these were such melancholy sounds, I couldn’t believe it. She couldn’t possibly know what they were saying, could she? The tank was very murky, so the belugas mostly stayed above water, turned away as if they couldn’t stand looking at us, couldn’t care less what we were doing. We’d destroyed their innate curiosity, which never caused harm, unlike ours, which made terrible things happen.

“They’re planning something. Just you wait,” whispered Trudy. She looked really rough, crazy, hadn’t slept in days. “Look at those big smug faces.” I wanted to get away badly. I could smell and sense the place I belonged in so sharply that it made my heart ache and my throat burn. Somewhere free but impossible.

The next morning, Trudy’s body was found floating in the beluga pool. People were surprised the whales hadn’t eaten her. But Trudy’s body was perfectly intact. The marine biologist wondered if maybe she’d fallen in the pool and one of the belugas had pinned her to the bottom of the tank. Maybe Trudy just drowned from the panic, but the belugas did seem very suspicious all of a sudden, with their sideways glances and permanent grins.